The negotiation skills of Luis Guillermo Solís’ administration were tested this week by protests on Tuesday in which hundreds of residents from several Costa Rican communities blocked main roads in three provinces for eight hours.

The civic National Housing Forum organized the protest to call for the construction of more housing developments for the poor.

Starting at 6 a.m., forum leaders representing 63 communities coordinated simultaneous roadblocks that caused several traffic jams, including on Route 27, which connects the capital with the Pacific province of Puntarenas. Other affected areas included the canton of Goicoechea, north of the capital, and the provinces of Heredia, Cartago and Limón.

Another group of 60 protesters gathered at Casa Presidencial in the southeastern San José district of Zapote, where they blocked traffic and demanded to meet with President Solís. Officials responded by offering a meeting with Presidency Vice Minister Ana Gabriel Zúñiga, instead.

Later, Casa Presidencial and Housing Ministry officials issued a press release highlighting “the administration’s determination to find solutions for these people.” The statement also noted that in the first three months since the administration took office, the ministry held 64 meetings with housing groups leaders, and from May 8 to Aug. 26, officials issued 2,804 housing subsidies for poor residents.

“We have created sufficient opportunities for dialogue, to reach agreements, and the number of meetings we’ve held with groups and leaders across the country is proof enough,” Housing Minister Rosendo Pujol said. “We already have begun addressing those requests, and we’re eliminating barriers they [protesters] faced in past administrations when they applied for government assistance.”

Administration officials say they have formed inter-agency commissions to seek housing solutions in several areas, including La Carpio, Triángulo de la Solidaridad and Finca Boschini in San José, Guararí in Heredia, Limón 2000 in the Caribbean, and Santa Marta in Puntarenas.

“Through these commissions, the Housing Ministry has negotiated the relocation of families to new housing developments currently under construction in Upala in Alajuela, Matina and Guácimo in Limón, and Turrialba in Cartago,” Pujol said.

No easy solution

Slum areas in San José represent a greater challenge, because most residents are reluctant to leave the capital in order to move to housing developments in rural areas.

“We tried to find solutions in nearby areas to avoid difficulties, … but only a few families were willing to leave the Greater Metropolitan Area,” the minister said.

Last month, residents of the southern San José canton of Desamparados grew hostile when a bus carrying residents from Triángulo de la Solidaridad – one of the capital’s biggest slums – arrived to inspect the area as a possible site for relocation.

Local residents blocked the bus’ passage and gathered in front of their homes in a communal display of disapproval. They also filed complaints with the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, or Sala IV, and the Environment Ministry (MINAE), arguing that the area, known as Mt. Tablazo, is the source of six potable water sources for a large number of residents in Desamparados and the Cartago canton of El Guarco.

Last Friday, MINAE’s Administrative Environmental Tribunal ordered the mayors of Desamparados and El Guarco to refrain from issuing construction permits in the area until MINAE could guarantee the protection of local aquifers.

Housing Ministry project director Marian Pérez Gutiérrez denied the ministry’s involvement in the transfer of Triángulo de la Solidaridad residents to Desamparados, saying that an owner of one of the Mt. Tablazo farms acted “on his own initiative” in bringing the group to the area. The landowner then hoped to sell his property to the government, she said.

Pérez told The Tico Times that ministry officials met with community leaders on Friday to reassure residents that the ministry is not considering the area for future housing projects.

Resident relocation is complicated, but the situation in Triángulo de la Solidaridad is urgent. Located northwest of the capital between the cantons of Tibás and Goicoechea, Triángulo de la Solidaridad sits smack in the middle of the government’s project to expand the Circunvalación, a belt route bordering the capital’s central canton.

The project, known as Circunvalación Norte, entails construction of a 4.1-kilometer stretch of road connecting the northern and western sectors of San José. About 525 families live in the slum, including a large number of Nicaraguan immigrants, according to Housing Ministry data. Those residents must be relocated if the project is to move forward.

The Housing Ministry already has begun notifying a first group of 191 families that they must leave by Dec. 15 in order for the project to begin on schedule. Families will be relocated in small groups of no more than 10-15 families per location, an effort by ministry officials to avoid another Mt. Tablazo incident.

On Wednesday, Pérez said officials are interviewing families to determine who is willing to relocate.

“We have 161 houses ready for those interested in moving right now to Acosta [south of San José], Puntarenas, Los Chiles [northern Alajuela] and Turrialba. We will finish interviewing families next Friday to evaluate how many will be willing to move to these locations. For the others, we have funds from the Mixed Institute for Social Aid to pay rent for a few months in order to begin work as planned on the Circunvalación,” she said.

Pujol defended his office’s work during the first three months, saying, “Projects that have been stalled for several years are now moving forward.” Because of that, he said Tuesday’s protests are unwarranted.

“We agreed on a Dec. 15 deadline for these 191 families because many have children and need time to finish the school year. But all of these families will be relocated,” Pujol said.

According to ministry officials, Triángulo de la Solidaridad will disappear, with remaining residents relocated in the next two years. That, said both Pujol and Pérez, will give the administration time to build new housing projects.

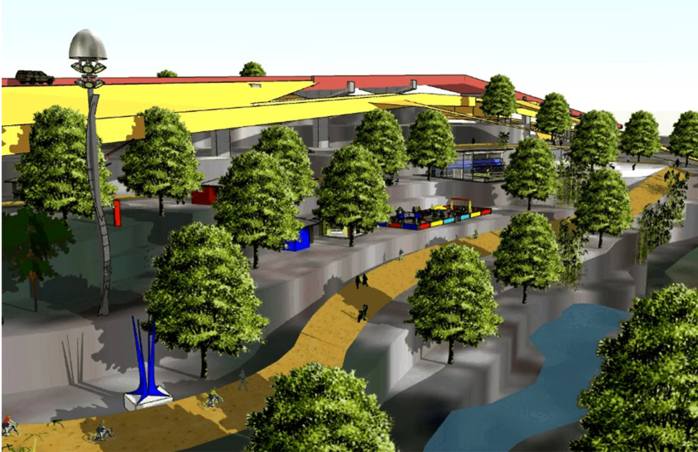

And in addition to a new road, one of the country’s biggest slums will become a park with a forested area, housing officials promised.