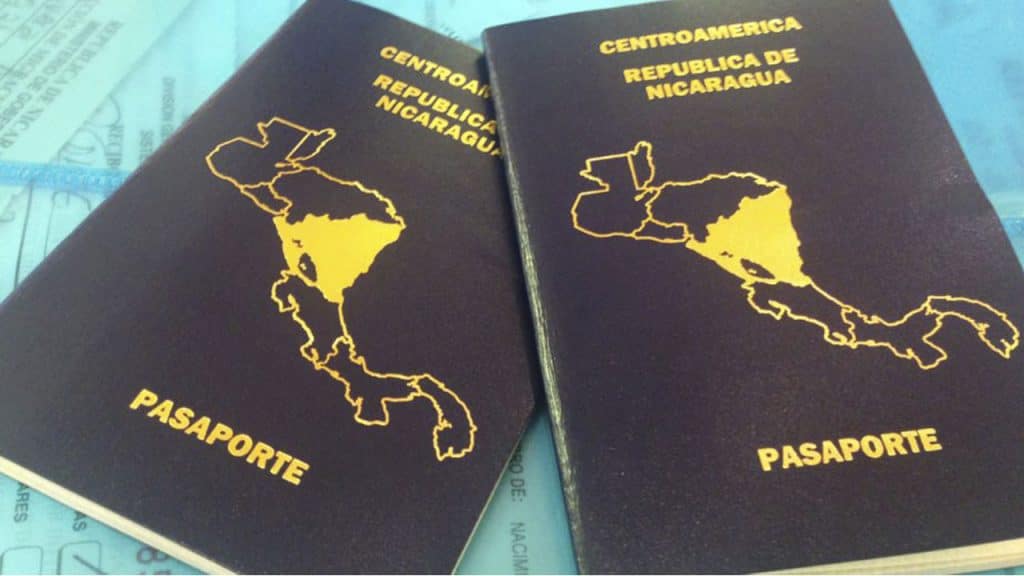

Nicaragua’s National Assembly ratified a constitutional reform today that ends the right to dual nationality, forcing Nicaraguans to lose their citizenship if they take on another one. The change hits hard at the large exile community, many of whom have fled repression and sought new lives abroad.

Lawmakers, under the control of the ruling Sandinista party led by co-presidents Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo, approved the measure in its second legislative session. The reform alters articles 23 and 25 of the constitution. Now, the law states that Nicaraguan nationality ends the moment a person acquires foreign citizenship. Foreigners who want Nicaraguan nationality must give up their original one, with an exception for Central Americans by birth who live in the country.

The assembly posted on social media that the law reinforces Nicaraguan identity as a commitment to independence and sovereignty, not just a title. Assembly president Gustavo Porras said last year the ban would not apply retroactively, sparing those who already hold dual citizenship. Yet opposition leaders express doubt, pointing to the government’s history of stripping nationality from critics.

This reform builds on a broader constitutional update from 2025 that strengthened Ortega and Murillo’s authority. The couple, in power since 2007, have faced accusations of curbing freedoms after protests in 2018 killed over 300 people. They called those events a U.S.-backed coup attempt.

Hundreds of opponents have lost their Nicaraguan citizenship in recent years, labeled as traitors and expelled. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights raised alarms last year, warning the change could lead to statelessness and violate international standards. Nicaragua is bound by the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, which aims to prevent people from losing nationality without gaining another.

Exile groups, like the Great Nicaraguan Opposition Confederation, called the law a punishment from the dictatorship. They predict it will push more people into forced exile, cutting ties to family, property, and roots. Many Nicaraguans abroad rely on dual status to send remittances home or visit without barriers.

The timing follows recent releases of about 20 political prisoners last weekend, amid U.S. pressure after the fall of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, an Ortega ally. Still, NGOs report dozens more remain jailed, some arrested for online posts celebrating Maduro’s ouster.

Reports suggest Ortega, now 80, deals with health issues, prompting Murillo, 74, to tighten control and prepare for succession. The regime has closed universities, NGOs, and media outlets, while expelling religious figures.

For exiles, the law means real losses: no more Nicaraguan passports, voting rights, or easy access to documents like birth certificates. Properties could face complications in sales or inheritance. One opposition figure in exile said it feels like a final cut from the homeland.

Nicaragua’s economy depends on migrants, with remittances topping $4 billion last year. Critics argue the ban could hurt families and deepen isolation. The assembly passed the reform unanimously, with 90 votes in favor. It takes effect immediately, though details on enforcement remain unclear. Opposition voices abroad urge international action to protect vulnerable Nicaraguans.

As borders tighten, the exile community braces for tougher choices between new opportunities and old ties.