MONTGOMERY, Alabama – All roads led to revolution in the Costa Rica of 1948, when a hacienda owner named José Figueres Ferrer would overthrow the government and soon after become known as the father of modern Costa Rican democracy. It was an event that shaped the future of a country, its people and their place in Central American politics.

The story of one important figure in the revolution, however, began not in the sprawling Costa Rican mountainside but in the foothills of the U.S. Appalachian Mountains, with a young Alabama woman.

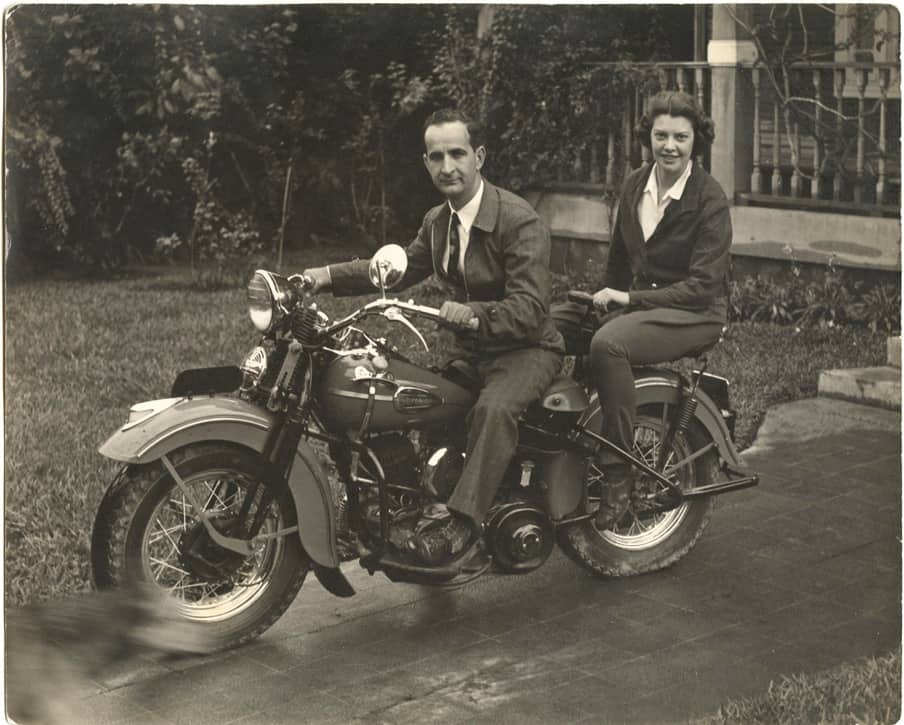

Henrietta Boggs was a 22-year-old English student at Birmingham-SouthernCollege in this southern U.S. state when she visited Costa Rica in the summer of 1940. She went to visit her entrepreneur uncle and aunt, who had purchased an old coffee plantation in the Central Valley.

When Figueres was invited for lunch one day to discuss the coffee business with her family, a romance started that would go long past that summer. It would be a decade before Boggs returned to Alabama.

They married in late 1941, and the relationship lasted 11 years, right through the 1948 revolution led by Figueres, the success of which established him as the dominant figure in Costa Rican politics.“Don Pepe,” as he was affectionately known, went on to serve three terms as President (1948-49, 1953-58, 1970-74).

Now residing in one of the historic districts of the Alabama state capital, Boggs, 89, vivacious as ever with a personality sharp as tacks, keeps informed on Costa Rican politics through the children she had with don Pepe, Marti and Muni. The former Tico Times contributor – she wrote a 1970s series called “La Macha” about her life as the first wife of the legendary don Pepe – has been living in Montgomery for about 20 years now, and was a founder of Montgomery Living, a monthly city magazine. She sold the publication but still works as a staff writer doing monthly feature stories.

The lady known as “La Primera Doña de la Revolución,” who still makes several trips to Costa Rica a year, sat down last month with this reporter to reflect on the revolution, don Pepe, and issues facing the nation.

TT: What was your first impression of José Figueres when you met him on your family’s plantation?

HB: I was immediately impressed by his magnetic personality. He had those strange, penetrating blue eyes, and when he looked at you it was like being hit with an electric shock. Then he had a wide and almost limitless range of knowledge about a great many things. So I was impressed, but quite intimidated by him.

What told you that you might marry him?

My aunt – who was always a little different – loved making predictions. She said a hurricane would destroy the National Theater, there would be a drought killing all the coffee plants … but one day she said to me, “You have to marry this man; he’s going to be President.” And the reason she knew, she said, was she had studied him carefully, and the curve of the back of his head was just as beautiful as a Greek statue, and that proved he was going to be President. That was her only prediction that came true.

As your romance developed, political issues were boiling as well. How did it affect you when the revolution broke out?

Muni, who was 2, and Marti, who was 4, and I were in the valley town of La Lucha as it was starting. Don Pepe had already moved the army out, but word came that the government would be attacking the town soon and we had to leave.We took off on foot into the mountains for days and days, moving at night, with just my brother-in-law and an oxcart full of rice and beans and water. Marti was old enough to walk, but I had to carry my daughter the whole way. Somehow we survived.

Had things gotten worse for the liberation army, we were set to walk 200 kilometers to Panama. Mercifully, that didn’t happen.

Had you bargained for that when you married don Pepe? What did your family think back home?

I kept looking around and thinking, “What in the world am I doing here? I should be back in Birmingham working for a newspaper, going to the country club and just living the normal life of a Southern woman.” Instead, here I was wandering through the mountains, scared out of my head, being shot at. I don’t know how long I went without being able to speak with anybody from Alabama, but I know the revolution was being reported back home. I think they even reported it was over before I got to a telephone to call my parents.

Don Pepe made considerable changes to the government after the revolution. What lasting effects do you see most prevalent today in Costa Rica?

First, the fundamental change in attitude, that government exists to solve social problems. For a long time it was “How will this piece of legislation affect my brother-inlaw?” instead of what it meant for the people. More technical, capable people were being put in important positions. Probably the biggest change of all, which will affect Costa Rica forever, was the disbanding of the armed forces, so that that money could be used to strengthen social programs.

As for other current issues, what is your take on the harsh opinions many Costa Ricans have of Nicaraguan immigrants as more have made their way into the country, and the perception of some that they have contributed to the increase in crime the country has seen?

When you have poor people coming in, quite often the crime rate goes up. Whether they are the ones or not, the Nicaraguans are the ones blamed for it. My perception of all this is that Nicaraguans are doing the work that Costa Ricans would no longer do.

Sowing the rice, planting the melons … and I have even been told that the coffee industry would just shut down if they weren’t there.

However, as you see in most societies where there’s a large immigrant group coming in, the first wave sets the foundations for the new families being formed; then the second generation goes to public schools and gets education; and the third generation gets to a point where they are leaders in government, business and education. In the next few generations, the Nicaraguans will be in politics, and a few more down the road there could well be someone of Nicaraguan descent elected President of Costa Rica.

In the United States, businesses used to hang signs saying, “Irish need not apply”; then we had John F. Kennedy elected. That’s what’s going to happen to Costa Rica.

Going back to your life today, what does it feel like now, living a calmer life in Alabama and reflecting on the role you played in Costa Rican politics?

It always had such an air of unreality. The diplomatic way of life was so formal, so you always had things you were and weren’t supposed to do. I’m not sure if I enjoyed it so much because I felt inadequate in some sense, and that I wasn’t doing as good a job as I could.

But the Costa Ricans weren’t hesitant to accept a foreigner. I served as a conduit between many regular people and don Pepe. I helped many people get to him with questions they had, issues they wanted addressed. But at the same time I was constantly ill at ease that I wasn’t doing as good a job as I could have, and looking back now I’m certainly convinced of it.

After all of this, what does the country mean to you personally?

It will always be for me a second home and second country. It’s such a beguiling place, and I have family and so many memories there. It’s too much to list.

Henrietta Boggs, the Alabama woman who married a revolutionary President of Costa Rica and became the First Lady of the Revolution, died earlier this month at 102.

In honor of her life and role in Costa Rica’s democracy, we’re republishing our 2007 interview with Boggs. We also highly recommend reading The New York Times’ obituary, which highlights her successful push for women’s suffrage in Costa Rica.