You can forgive David Crosby for not remembering the Washington-area venue he was playing in the summer of 1994 when his liver finally gave out after so many blurry years of dope and drink. But he does recall that it took two guys to help him off the stage and back onto the tour bus.

“I know it was D.C. because I went to — what’s the fantastic hospital?” he asks, then remembers: “Johns Hopkins.” At the Baltimore hospital the day after the show, doctors delivered what he calls “very tough news.” You have hepatitis C, they told him, and you will die soon without a liver transplant. He received one in November of that year.

“And now I’m a very healthy guy,” says Crosby, 72, sounding jovial and still grateful in a phone call from a stop on his latest tour. These days, the folk-rock legend is promoting “Croz,” his first solo album since 1993, which features guests such as Mark Knopfler and Wynton Marsalis.

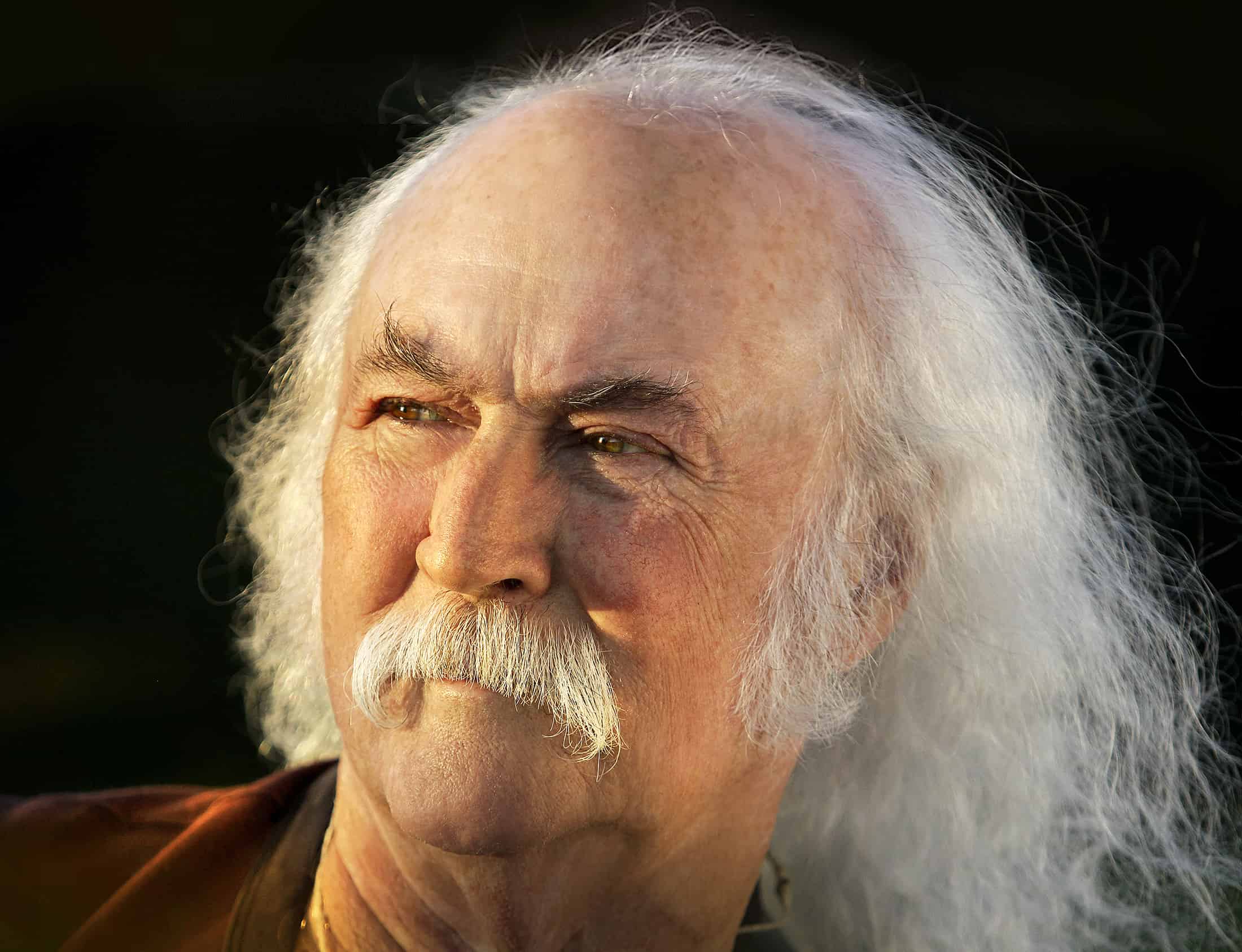

“I am an incredibly lucky human being,” says Crosby, whose walrus moustache now invokes Wilford Brimley more than the Woodstock vibe. “I’ve got a great family, I’ve got a fantastic job, and I was supposed to dead 20 years ago.”

For live music historians out there, it’s almost certain that the fateful 1994 gig was at Wolf Trap, where Crosby and bandmates Stephen Stills and Graham Nash appeared on Aug. 2 that year. Crosby will play three sold-out-shows at the Barns at Wolf Trap on Monday, Tuesday and Thursday.

Topics during a chat with Crosby can meander from the Byrds, the band he was fired from in 1967, to the ill-fated 2012 collaboration CSN attempted with the famed producer Rick Rubin. Except when he’s talking about serious matters – like the track on his record deploring U.S. drone strikes – Crosby dissolves into merry laughter throughout.

But he assures me there are no chemical enhancements involved anymore. No way.

“It’s all done with,” says the man who served time for a cocaine and guns rap in the 1980s and nearly lost his life to addiction.

He is clearly pleased with the new album, and the fact that Rolling Stone’s review praised his “triumphant solo return.” He says it emerged mainly from songs he and his son, James Raymond, had been writing, both alone and together.

“I had these songs,” Crosby says, “and they’re good. I don’t know what else to do except make a record. Of course we had no money. But my son James has a studio at his house; so I would go down and sleep on his couch and we would get up in the morning, he’d make me an omelet, and we would go to work. The result is this record. I know this is not very humble, but I think it’s some of the best work I’ve ever done.”

Crosby’s first solo album, 1971’s “If I Could Only Remember My Name,” was panned in Rolling Stone as mediocre, he recalls, but it still sells and enjoys acclaim. In 2010 it ranked No. 2 on a list of “Top 10 Pop Albums of All Time” published in the Vatican’s official newspaper – below the Beatles’ “Revolver” but above Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon.”

“Now is that weird or what?” Crosby asks. “We were all completely flummoxed. And I got an email from David Gilmour saying, ‘Dammit!’ ”

Cue gasps of hilarity as Crosby recalls the belly laughs he shared with the Pink Floyd guitarist and singer.

Why would the Holy See single them out? “Neither one of us knows why we were on there at all in the first place!” Crosby says.

In their heyday, CSN (and Y, when Neil Young joined in), were renowned for their exquisite vocal harmonies, picturesque lyricism and polished folk-infused sound. Some of today’s young “beardo” bands – so named for their hippie-style whiskers – cite CSNY as influences. Does Crosby have any favorites?

“I really like Mumford and Sons,” he says, “but there are number of younger bands that really can do it.

“And if we’re any part of inspiring them to do that, good, wonderful, that makes me feel great,” he adds. “I have actually gone to a Fleet Foxes concert, and they can sing, they absolutely can. I really, really like them. … I think they will mature as songwriters and probably be a lasting band.”

CSN itself just seems to go on and on – with or without Young, who has periodically rejoined the ensemble. Among rock stars, the proverbial “creative differences” with bandmates tend to be an occupational hazard. Byrds frontman Roger McGuinn and bassist Chris Hillman clashed with Crosby, later describing him as an arrogant jerk.

“You know when they fired me, they said, ‘We’ll do better without you,’ ” Crosby reflects. Then he guffaws explosively.

“I think Roger probably regrets that. Maybe that’s why he won’t go out on tour with me. But I would love him to do it, because he was very good.”

And why did CSN part ways with Rubin, the producer who’s famed for his ability to reinvigorate flagging careers?

“It just wasn’t a good chemistry,” Crosby says. “We produced all our own records except for one that Glyn Johns produced. Now Glyn Johns produced the Beatles, the Stones, Clapton, Hendrix, just about everybody at one time or another. … With him it did work; with this guy it didn’t work.”

One track on the new solo record, “Morning Falling,” recounts the collateral killing of an Afghan family in a drone strike. It brings to mind the activism and protest songs Crosby and his mates have long been known for — notably “Ohio.”

“A lot of our job is to make you fall in love, or express an emotion, or to take you on a voyage,” he says. “But part of our job is to be the troubadours, to be the night watch. . . . saying, ‘Hey it’s 12 o’clock and all is well,’ or ‘It’s 11:30 and we’ve got a bunch of monkeys in Congress.’ ”

Crosby has been described as a man worth many millions of dollars, a notion he calls complete nonsense. “I don’t have any money at all,” he says, chortling again. “I’m not going to make any money on this tour . . . I don’t mind.

“One of these days Neil will call and I’ll go and make some money. In the meantime I’m very happy to be making music.”

© 2013, The Washington Post