PUERTO VIEJO, Limón — Upgrades to Route 256 in Limón, the main road stretching 20 kilometers through several South-Caribbean tourist towns, has raised far-reaching questions about the benefits of changing the old dirt roads to new paved ones.

So-called improvements to Route 256 have resulted in an increase in speeding vehicles, putting people and wildlife on edge for their safety.

Having seen the deaths of domestic and wild animals, and even a recent death of a young woman on the new road built by Costa Rica’s National Roadway Council (CONAVI), local residents are doing everything they can to feel safer.

Andrea Mora, a resident of Punta Uva, met with The Tico Times at Restaurante Selvin, a restaurant on Route 256 at which she works that has been impacted by the recent road developments.

“Two years ago, when the government decided to take ownership of the road and start maintenance, we didn’t realize how much this would change and affect our lives,” Mora said. “We don’t feel safe.”

According to a letter written by Mora and other community members to the Regional Traffic Engineering in Siquirres, a canton 120 kilometers north of Puerto Viejo, “In September 2018, there was an incident in which a British tourist was hit by a motorcycle. The tourist, Mr. Pete Miller, has permanent scars on the entire left side of his body. Days later, [the woman] who was the motorcycle passenger died of a concussion.”

Mora said they didn’t know the name of the woman because she was from a different town, Hone Creek. In an attempt to reduce the speeding on the road, as well as the number of wildlife being killed, community members also requested in the letter for the placement of speed bumps and signs on the road.

Rich Coast Project volunteer Felix Charnley said that due to the government’s lack of response to petitions asking for speed bumps and signage, neighbors created their own speed bumps. Less than 24 hours after they were installed last December, the speed bumps were demolished by CONAVI authorities.

“The community in the area was outraged by the desire from CONAVI to act quickly to get these out but not to act with the same speed to reduce the recklessness of drivers and disrespect to people,” Charnley said.

In June 2015, CONAVI took ownership of Route 256 from the municipality of Talamanca and began maintenance, making the road wider to allow for easier and faster access through the area. Although cycling and walking are both popular choices of transport near Puerto Viejo, the upgrades to Route 256 left out sidewalks and bicycle lanes.

Before the maintenance, Julie Carson, a neighbor of Mora’s, said “there wasn’t the worry and stress about having such a dangerous road. People didn’t drive so fast. There seemed to be more respect, and now it’s a freeway through a little town. It’s crazy.”

Karol Méndez, an urban mobility activist who leads CicloVida Caribbean Neighbours Association, a community group that works to preserve safety among pedestrians, cyclists, cars and domestic and wild animals, says Route 256 is vital as it unites all the surrounding communities and is the backbone of an ecosystem that strives to stay healthy and harmonious.

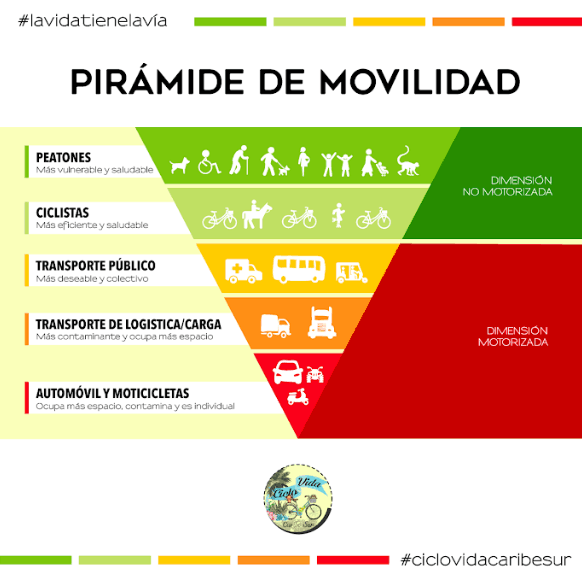

“Nowadays, it’s like the cars, trucks, busses and motorcycles are the most important thing, leaving people and bicycles at the bottom of the pyramid,” Méndez said. “We need to turn this around and put people first. We need to focus on life itself.”

Méndez is working with municipalities across the country to spread this message and to workshop solutions to fix similar issues in other provinces. When she moved to the Caribbean coast from San José, she said people in the community were asking authorities to implement cycle paths. Her response, in line with the paradigm shift of focusing on life, not vehicles, was to rethink the philosophy of the cycle path.

“It doesn’t give the cyclists the real priority they need,” Méndez said. “The bicycle itself is an identity, a symbol in the Caribbean. Everyone has one. It’s not like in San José where people think that bicycles are for poor people, police or kids. […] We want to make people understand that it’s the best means of transport you can have.”

The chances of seeing wildlife when biking from Puerto Viejo to Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge, for example, are incredible. This is a route for animals too, and they’re used to using it — and not just to cross the road. Sheep and horses use the route just as if they were people. When you’re being passed by a car speeding at 100 kph, it makes you feel more than a bit uneasy. The speeding is the leading cause of death for wild animals and bicycle accidents.

Since CicloVida is supported entirely by volunteers, the data they’ve collected on animal deaths doesn’t accurately depict the situation. However, a 2017 report cited more than 50 incidents.

Since CONAVI took over the road in 2015, it has been difficult for the public to find solutions to their concerns.

When requests toCONAVI are sent, “nothing happens,” Mora said. “There are so many economical and political interests in the road and it is all coming down on the tourists and locals in the community. For example, we rent bikes, and I noticed people are renting less bikes because people are worried about the speed limit.”

The official speed limit is 40-60 kph, “which isn’t happening,” Mora said. “The speed limit isn’t being regulated. We lose wild and domestic animals every day. Our dogs, cats… It’s crazy.”

According to Article 137 in the Mobility and Security Cycles Law from The Legislative Assembly of Costa Rica, when a town such as Puerto Viejo has a prominent bicycle culture, the law mandates a speed limit of 40 kph. Méndez says she has met with the Public Works and Transport Ministry (MOPT) many times to remind them, and “last year, MOPT made it a project of priority.”

Outside of Talamanca, Méndez has been presenting their case to municipalities in La Fortuna and Puntarenas, which have declared her mission as a priority for investment pilot projects to see if they can work in their communities as well.

“We are going to schools, because I think that kids are the ambassadors of information,” Méndez said. “We need to create a language with signs. Not just speed signs, because they are not enough. Some kids in a school I presented at in Puerto Viejo thought of one that would say, ‘We love people, animals and bicycles, and they are a priority.’”

According to Méndez, employees of MEPE, a bus company that operates a route between Puerto Viejo and San José, are open to working with CicloVida to create strategies to encourage people from San José to come by bus instead of car.

“There is an interest in people working in mobility to talk about what is happening in Costa Rica,” Méndez said. “There is also an opportunity to create job opportunities.”

For example, rental bikes in the area can be rusty with weak chains that snap while going up hills. Méndez says she is proposing to put bicycle maintenance at the entrance of main streets.

CicloVida has made an official request to MOPT for the technical studies needed for the workshopping of their pacification project in Talamanca. In short, the request outlines the need for a diagnosis and initiatives for the reduction of traffic accidents and violence on public roads. The goal is to establish a comprehensive plan of action in the short, medium and long term to deal with the situation.

Until then, Mora and many of her neighbors will remain on high alert whenever they’re on Route 256.

*Corrections: This story was updated on Jan. 25, 2019. The original story quoted Carol Meza from the CicloVida Caribbean Neighbours Association, her name is Karol Méndez.

The original article also stated Ciclovida made an official request to MOPT for their pacification project across the country. It was for a project in Talamanca, not the whole country.

This story was made possible thanks to The Tico Times 5 % Club. If only 5 percent our readers donated at least $2 a month, we’d have our operating costs covered and could focus on bringing you more original reporting from around Costa Rica. We work hard to keep our reporting independent and groundbreaking, but we can only do it with your help. Join The Tico Times 5% Club and help make stories like this one possible.