What time of the year is it? It’s coffee picking season. Coffee all over Costa Rica is in full swing. In my beautiful high-altitude mountainous community along the Panamanian border, that means hundreds of indigenous Panamanians cross the border to pick coffee from September to February.

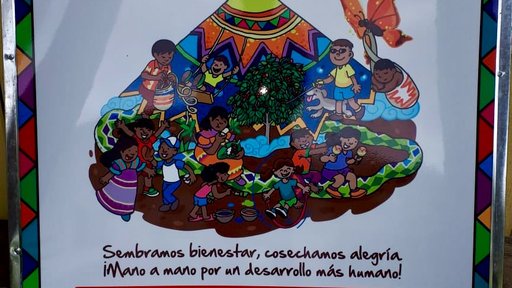

On my host family’s coffee farm, there is a house that can accommodate up to 30 people. They house indigenous families who travel from afar to pick our coffee. With the help of Icafe and UNICEF, the Casa de la Alegría (House of Joy) stays open throughout coffee picking season from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m., Monday through Saturday.

These organizations subsidize utility costs and pay for a cook to provide all meals for free. In addition to standard lodging accommodations such as kitchens, bathrooms, and showers, La Casa de la Alegría also offers free childcare. They provide meals, snacks, nap time, and loads of toys for children. This lets both parents pick coffee and earn money while their children are safe and cared for.

My community is unique in that it is one of the only coffee-producing regions of the country that provides these resources. With a local economy dominated by coffee, it’s incredible to see the impact these services have had supporting local families during the labor-intensive, long work days of the coffee season.

People pick all day, rain or shine because. For a lot of them, this is their only source of income. With a basket strapped to their waist, workers will spend hours picking ripe red berries nonstop. Their pickings are measured using cajuelas, which are 1-foot square boxes.

Depending on their experience and ability, a person can usually produce 10 to 15 cajuelas during a typical eight-hour workday. Each person’s cajuela count is tracked over the course of the work week, and on Saturdays, workers are paid approximately ₡1,000 (about $1.60) per cajuela.

Filled to the brim with bright red berries, cajuelas are then transported to a beneficio (coffee mill) to be washed, dried, and sold to a roaster. There are many beneficios in the southern region of the country, including three in my community alone.

Each beneficio pays farm owners per fanega (one fanega is 20 cajuelas), the price of which can vary depending on the season, origin of the beans, and quality of the harvest. All of the coffee picked from my host family’s farm is transported to a beneficio that is in accordance with the local coffee cooperative because my host dad, Noé, is a member of the co-op. Usually, the farmers who sell to the cooperative or the cooperative’s beneficios receive more money since they pay an annual fee to be a cooperative member.

Once the picked red berries arrive at the beneficios, the outer fruit is removed to expose the bean. From there, the beans are washed, placed in a dryer, stripped of their casing, and dried once more.

The beans are constantly being tested throughout the drying process for density and taste. There is a whole number system in place that the coffee industry uses to classify beans which roasters use to buy the specific beans they like.

The cooperative’s beneficio in town even has a vibrating machine that separates beans by weight into A, B, or C quality. At the culmination of the drying and testing process, the leftover beans, also known as the golden bean, are sold by the beneficios to roasters, such as Starbucks and other coffee shops.

Besides my frequent splurges on a $5 Pumpkin Spice Latte or Dirty Chai back in Seattle, I didn’t initially know much about the coffee industry or the extensive work that allowed me to enjoy my morning cup of joe.

Peeking behind the curtain at the inner workings of the industry has been an incredibly informative aspect of my service experience. Aside from learning about the interesting nuances of local coffee production, I was also exposed to some unfortunate realities of the industry. Coffee throughout the world is in a crisis.

Prices for this season have hit an all-time low in New York. Climate change is killing farms. Many people have stopped farming coffee altogether because they continue to lose money.

In this current season, the beneficios are only paying the coffee farmers ₡1,000 (about $1.60) for each cajuela to pay the people who are picking the coffee. Last year, the price paid to farmers per cajuela was ₡4,125 (about $6.65).

Being able to view every step of the process as a Peace Corps Volunteer, from the hours workers spend out in the fields picking berries, to the intricate steps required to produce the coffee bean we have come to enjoy (and almost depend on) back home, has dramatically transformed my perception of coffee.

Coffee keeps the U.S. running, and we’ve grown accustomed to paying through the nose to satisfy our caffeine addiction. Meanwhile, people around the world, like the locals in my community, are picking baskets upon baskets of coffee for $20 a day.

It blows my mind and humbles me. My appreciation for a good cup of coffee has undoubtedly skyrocketed, and I hope by sharing these insights, you will find a new-found appreciation as well.

The Peace Corps photo series in The Tico Times Costa Rica Changemakers section is sponsored by the Costa Rica USA Foundation for Cooperation (CRUSA), a proud financial supporter of Peace Corps Volunteer projects nationwide. Learn more here. To donate to support the Peace Corps Costa Rica, visit the official donation page. Volunteers’ last names and community names are withheld from these publications, per Peace Corps policy.

Connect with the Peace Corps Costa Rica on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.