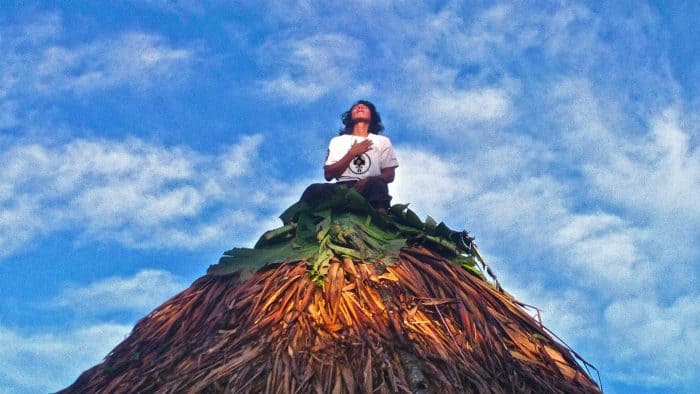

Preserving the ancestral traditions of Costa Rica’s eight indigenous cultures: that’s the mission that the Jirondai Project has been pursuing for 12 years now.

The project has connected indigenous people from around the country with non-indigenous people with expertise in art, music, anthropology, ethnology, gastronomy and other areas. A special focus for the project has been indigenous chants, songs and language, which in many cases have begun to vanish slowly over time. Today, the project seeks to provide indigenous groups with the tools they need to document culture and traditions from an audiovisual perspective for safekeeping by younger generations.

The project’s name and logo are inspired by the Gnöbe Buglé indigenous community.

“There’s a figure in the history of the Gnöbe Buglé from Costa Rica and Panama that’s called jirondai. It’s a shaman… They said that it was a being with two faces. One of the faces knew about the Gnöbes past, and the other one saw the future,” Luis Porras, founder of the Jirondai Project, told The Tico Times.

With this in mind, Porras, a journalist and musician, has worked to keep creating content that pays homage to Costa Rica’s indigenous communities. When he was 18 years old, he lived in South Dakota for a time and met descendants of the Sioux as well as the Pine Ridge community. He began to wonder how indigenous groups in Costa Rica were living and, later on, had the opportunity to meet indigenous leaders here struggling to maintain their cultures.

One such leader is the Cabécar jawá (doctor) Luis Salazar, who has been working along with Porras and the rest of the collaborators of the Jirondai Project during the past five years. Salazar lives in the mountains of Chirripó; it takes him 10 or 11 hours to walk down the mountains to then take two buses to San José. His joy in teaching younger generations about his culture is what drives him to participate in Jirondai.

On a rainy afternoon at the Ecole Travel Tourism Agency in Barrio Escalante, east of San José, The Tico Times sat down and spoke with Porras and Salazar. Excerpts follow.

How did you two get to know each other?

LS: It’s been five years since we met here in San José.

LP: A very good friend of ours, Elvis Vitar, who runs and is a Bribri music teacher, lives in Uatsi and teaches in Amubri. He’s a marathoner, and he [met] Luis at a race called the Ruta Run, which is 150 kilometers with the Tarahumaras from Mexico. Immediately, Elvis called me and told me that he wanted me to meet a friend that was running with the Tarahumaras.

Luis is a master of the culture, a doctor and a singer. He also represents maybe one of the most important pillars to understand decolonization. Meeting Luis and the community of Alto Telire, where Luis lives, is to discover something very important about decolonized thought… he did not go through any traditional elements of colonization. Not even school.

The biggest colonization Luis has is his friendships, having friends in Pérez Zeledón or San José. It’s the biggest counterculture he knows, but it’s not going to school to learn from a Sikua (foreign) teacher or going to Church to be evangelized.

How many people participate in Jirondai?

LS: Many. It’s hard to count.

LP: For percussion we have Isaac Morera, who’s also a percussionist at Infibeat. Andrés Cervilla is also working with us. Luis Mario Marín, who’s the guitarist. Johnny Gutiérrez. Paloma Coronado, who is a Mexican-Peruvian singer.

We’re actually a really big collective, including academic musicians like Andrés and people who are partially musicians like me. We have anthropologists. We have people from the communities: singers, doctors, elementary and high school teachers.

There’s also the gastronomic part with Pablo Bonilla, which is oriented to erase [the idea] that the poor indigenous people from the mountains are dying of hunger and we must help them with cans of tuna. It’s unjust to have masters of food security [in our country], and telling them they’re dying of hunger. In our national gastronomy, we don’t having any vestige of the marvels they use in the mountains to survive.

LS: Sometimes we’re told that they’ve found indigenous people who live in Alto Telire that [supposedly] are dying of hunger …it’s a lie [that’s told].

They eat natural food and a lot of food. There are a lot of crops. When I return home they’re OK and working a lot. They’re very happy and are not dying of hunger.

A few days ago some girls were asked if they were hungry and they did not speak Spanish, so they did not understand well. They just answered yes, and then the other people believed that, and then it’s published that we’re dying of hunger and it’s not true.

During the political campaign you published a video with indigenous people speaking about the elections. What was the result?

LP: We’ve never gotten into anything political. We made two short videos. Many people saw it, and that generated a lot of things. We were treated badly and were told many things. Even the men from the communities that appeared in the videos were treated badly. I think the country still doesn’t know what it saved itself from. Seeing the threats that the people received after participating in the video, we notice the craziness that’s behind it.

How did you choose to focus on music and audiovisual production?

LP: Because it’s what allowed us to speak to more people without the people feeling that it was an anthropological lecture. It made it possible to go to the bar El Observatorio and perform… We’ve played at the National Auditorium, the National Theater, the Melico Salazar Theater, and now we’ll have four dates to perform at the Vargas Calvo to film an audiovisual piece that will document the old singers due to the generational change we’re looking for.

I want to generate a dialogue with new voices in communities that want to explore strange and unusual places. Like suddenly taking a public space… and creating a new relationship with music. Young people who do reggae, hip hop and dancehall, but in Bribri and Cabecar.

What motivates you?

LS: For me it’s very important to keep on with this work for the rest of my life. I hope my groups, families and students keep going onward. I prefer that they keep learning and growing, and if I become tired or am lazy about it, then my students continue with it. It is important work, like the work of my grandfathers and grandmothers’ work who worked many years, the caciques who worked thousands of years on the Earth and still keep working. We must work like them. We move on and it’s very important for us. We keep going on with the project.

LP: This year, Spanish Cooperation is giving us a hand to produce content. We’ll be classifying what we’ve recorded and also produce a lot of content for radio, which is a joint project with Salvador Vayá, who has opened the doors for us at the Farolito and Casa Caníbal because it’s about the new generations taking on this cultural heritage.

Listen to one of Jirondai Project’s albums called Sesiones Quetzal:

“Weekend Arts Spotlight” presents Sunday interviews with artists who are from, working in, or inspired by Costa Rica, ranging from writers and actors to dancers and musicians. Do you know of an artist we should consider, whether a long-time favorite or an up-and-comer? Email us at elang@ticotimes.net.