Art that helps build a collective imagination depicting the vibrancy and liveliness of Costa Rica’s Caribbean region: that’s what characterizes the work of Adrián Gómez, more than thirty years in the making.

“The vocation, interest or inclination for art has always been present in my life ever since I can remember. That’s why I say that I was born an artist,” Gómez, 56, told The Tico Times.

When Gómez was just 12 years old, his mother enrolled him in the National Artisans Association (ANDE), where he learned woodcarving. Gómez went on to study at the Juan Ramón Bonilla School, founded by artists from Cartago including Hernán Hidalgo, Fernando Carballo, Luis Fernando Quirós and Jorge Valverde. Carballo would become an important source of support later on when Gómez set out to create art that would celebrate Afro-Costa Rican communities in Limón.

After graduating from high school, Gómez studied construction engineering at the Costa Rican Institute of Technology (TEC), but dropped out due to family issues. He began working in advertising agencies, which allowed him to study composition and colors that he transferred unconsciously to his self-taught art.

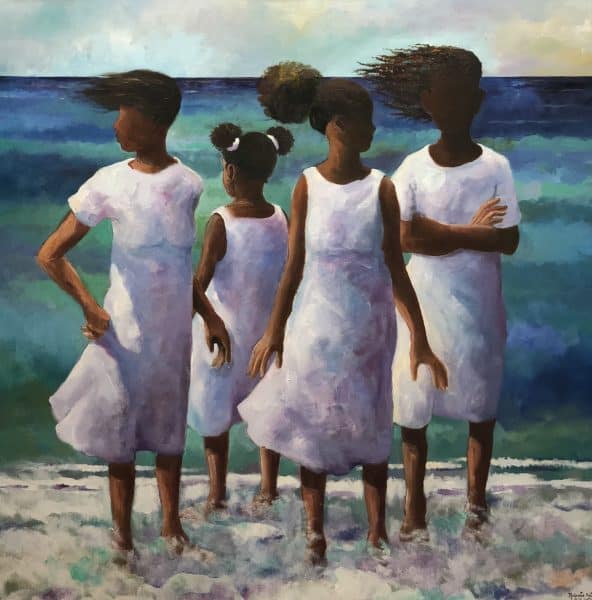

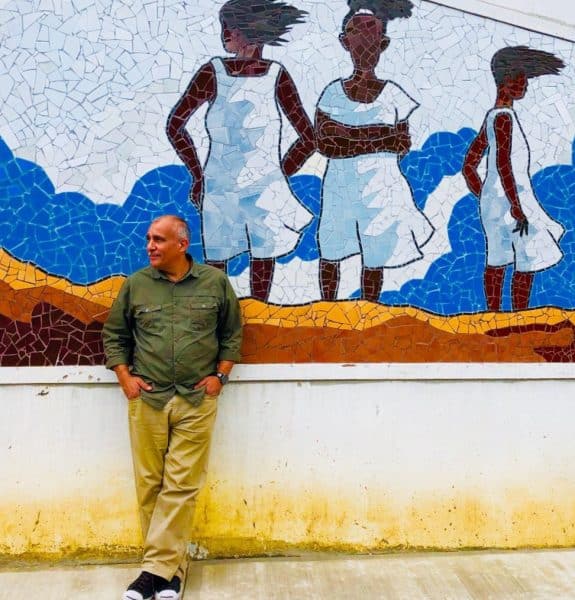

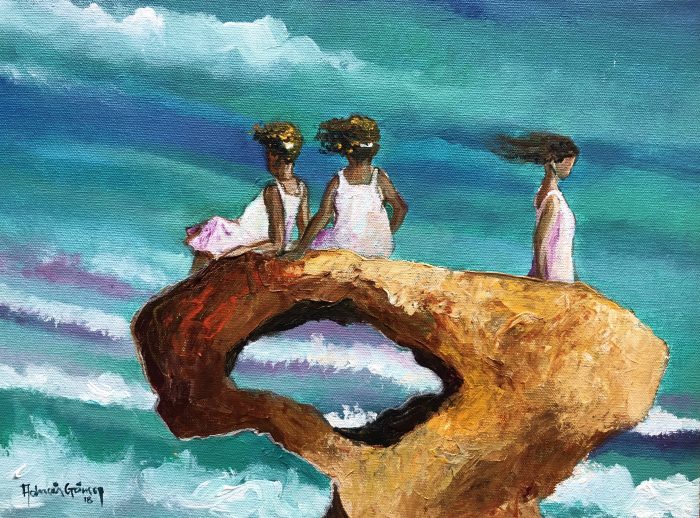

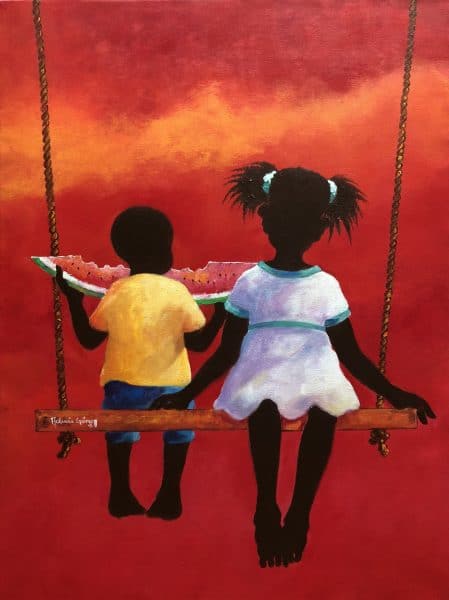

As his passion for art deepened, he found himself remembering childhood trips with his mother to visit his father, who was working in Limón. He began to incorporate his love for the Caribbean province into his art, especially focusing on black childhood; today, his paintings of faceless children joyfully playing or riding swings hung from clouds are instantly recognizable around Costa Rica. His work has been exhibited in the United States, Mexico and Guatemala as well.

On a sunny, warm afternoon at Entre Nous Café in Barrio Escalante, east of San José, Gómez sat down and spoke with The Tico Times about his life and work. Excerpts follow.

How did you come to depict Afro-descendants in Costa Rica’s Caribbean?

My father used to work in heavy mechanics, repairing trolleys, backhoes and all that sort of machinery. He worked for various companies, but a large percentage were in Costa Rica’s Caribbean region. My mother had to visit him to sustain their affection and love, and to get the money for our sustenance. We would go with my mother; there are nine of us. Obviously the nine of us wouldn’t go at the same time.

It had a great impact on me, all those images of the black Afro-descendant, but what surprised me the most were the colors they’d use in their heritage, in their traditions, in their way of dressing.

Of course, with the passage of time my reading of the Caribbean and its people has been enriched, and it’s very different from what [I thought] about the Caribbean when I began.

How has your artwork developed over the years?

With passion. With endeavor and clinging to build an imagination through the viewers’ interest, affection and empathy for the pieces. The artist needs a spectator: not only the viewer, but also the person who acquires [artwork].

Besides that, the artist must keep his mind stimulated. An artist is not only one that creates. You have to manage and build. In my short internship of thirty-something years in advertising, I never stopped building… I participated in fairs. I made paintings. I kept enriching my knowledge about techniques. I played with images in different environments, always respecting the thematic concept, which is color, because for me the Caribbean is color. My artwork is humanized, but in the end it’s an excuse I have to be able to apply the color of [the region’s] heritage.

How has persistence been important in your work?

What one is looking for in each image or painting is for the spectator to approach, to communicate more. Capturing the spectator is what paintings, sculptures or engravings do. I try to capture a person and retain his or her attention for as long as possible. That’s why people buy paintings and keep looking at them, year after year, and don’t get bored.

Can you tell us more about how you arrived at your specific focus?

I only paint a very small point in the whole universe that we call the Caribbean, because to speak about the Caribbean you have to talk about the people and their experiences in the sea. You’d have to speak about the people cultivating in the land. You’d have to speak about the dances. So, I only do a miniscule point, a minimal sensation.

To speak about the Caribbean, we’d have to speak about all the races or the mixture of races, understanding the Costa Rican indigenous as the first inhabitants of the Caribbean before the Spanish came, and when there were no borders. Then there’s the black community that the Spanish brought from the colony as slaves, and then you’d have to add the arrival of the Asian communities.

All this marvelous mixture of races in the Caribbean… but in my license as an artist I chose in my youth to differentiate myself and [focus on] the black inhabitants of the Caribbean zone.

Why did you choose not to paint facial expressions on the characters in your paintings?

There were faces in a lot of my paintings, but the spectators themselves taught me that I was wrong… People would see them and ask why they were sad or serious, or why they had their eyes closed. I understood that they were only concentrating on the emotional state of the face and that they were not seeing the position of the arms. They were not seeing the search for the whole composition. So, I decided over a period of years that I’d leave some things present, and some things absent.

When I left the [facial features out], what happened was that the spectator didn’t see someone they had to identify. The spectators built the silhouette of a child they had in their memory or in their affection. In taking away this girl’s or boy’s face, I went from speaking in singular to plural. I was not speaking about one child in the Caribbean. I was speaking about Caribbean childhood.

“Weekend Arts Spotlight” presents Sunday interviews with artists who are from, working in, or inspired by Costa Rica, ranging from writers and actors to dancers and musicians. Do you know of an artist we should consider, whether a long-time favorite or an up-and-comer? Email us at kstanley@ticotimes.net.