On Nov. 29, 2017, journalism student Paula Umaña published an in-depth feature for the weekly Semanario Universidad as part of Punto y Aparte, a mentoring program for young journalists. The Tico Times is proud to translate and publish her original piece with Semanario Universidad about therapeutic abortion in Costa Rica. Part I of III.

Because of lack of knowledge and fear of legal consequences, health care professionals contribute to the obstacles to therapeutic abortion in Costa Rica.

At 24, Lucía is in her last year of medicine at one of the country’s universities. When asked about therapeutic abortion, she says she remembers seeing it mentioned in one class and says “that it’s prohibited in Costa Rica”.

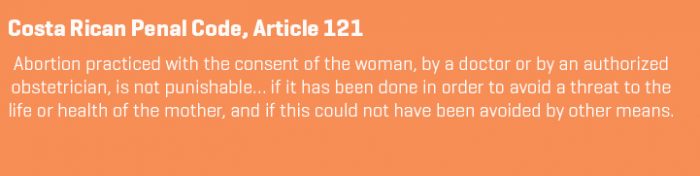

When she listens to information about Article 121 of the Costa Rican Penal Code, which establishes the circumstances under which abortion is permitted (otherwise known as therapeutic abortion), Lucía, with the tone of someone who is regaining her memory, says that it’s only done when the mother has a high risk of death due to pregnancy. About the word “health,” included in Article 121, she gives no answer; it seems that in her academic formation she wasn’t given one either.

Therapeutic abortion is subject to judgments and fears that travel from college classes to doctors’ offices. One of the interviewed obstetricians, with more than 25 years of practicing in the field, said that this type of pregnancy interruption is solely done when it’s demonstrated that the woman’s life is in danger.

When consulting her about the term of “health” incorporated in the law, she said that Article 121 does not specify a scope, and therefore “the judicial framework doesn’t allow [abortions] in cases where mental health is being affected, there are malformations in the fetus which are incompatible with the life.”

When national hospitals were contacted for this story, elusive responses reflect the fact that this topic is still a taboo – an idea reinforced by various interviewees who preferred not to be identified by their names for fear of critics in the medical field.

How many abortions do you think have been carried out in Costa Rica’s public hospitals during the past 20 years? The quantity registered by the Social Security System, or Caja (CCSS), is less than 80, in a country where 70,000 births are attended annually.

“There’s not even good training on sexual and reproductive rights, let alone something as specific as therapeutic abortion – and the training on ethics is not at all sufficient,” said Gabriela Arguedas, expert on public health atthe University of Costa Rica (UCR).

Luis Zamora, dean at the University of Medical Sciences (UCIMED), said that the topic of abortion is presented to the student from social and ethical points of view.

“The theoretical part, the laws that govern us and the situation that we have in the country are taught; when the student passes from general medic to specialist, that’s another situation, because the individual owns the topic and draws their own conclusions,” he sad.

Christian Blanco, dean of the Iberoamerican University (UNIBE), said his university addresses the topic of therapeutic abortion from an ethical, legal and objective viewpoint “so that the student has a notion of the legal aspects of the medical exercise and practice. The purely medical aspects specifically related to the health or risk of the mother are also reviewed.”

To obtain information about the training on therapeutic abortion that medical students at the UCR receive, Medical School Director Lidieth Salazar was contacted. She delegated the response to Dr. Flory Morera. However, despite multiple attempts, no answer was obtained.

Even though therapeutic abortion has been the law of the land for more than 45 years, the law is not applied effectively because of the doctors’ interpretation of the law, deficient academic training for health professionals on the topic, and the absence of abortion regulations in hospitals.

Medical resistance

During her first months of pregnancy, Aurora, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, discovered that her wanted pregnancy would not end well: her fetus suffered from an abdominal wall defect, and his organs were exposed.

But she continued with her pregnancy, not because she wanted to, but because her doctors, who knew the fetus had no possibility of living outside the womb, ordered that she continue. Her case would receive publicity afterwards in local and foreign media because it would be object of an international complaint, but at the time, she only wanted to get out of her hopeless pregnancy.

The doctors who treated her at Calderón Guardia Hospital in San José denied her a therapeutic abortion, using the argument that her life was in no danger. They set aside the physical and psychological impact she could suffer. Doctors resolved to prescribe anxiolytics, or anxiety inhibitors, to diminish the suffering of a mother who waited to give birth to a child she desired, but whom would never raise.

Seeking a clandestine solution was not an alternative, because in Costa Rica, the penalty for illegal abortion is from one to three years in prison. Carrying it out legally wasn’t an option either after a cycle that ended when she ran out of time. After months of intense pains, daily vomits and other affectations, Aurora gave birth.

“I can’t understand how the doctor who diagnosed my baby’s disease said that he wasn’t going to suffer. He was drowning in my womb for week, with the lungs outside the body, gutted by my organs. Afterwards, I learned that he sucked his own fecal matter until he was born. Even though he was not born, he agonized for five minutes,” she told the newspaper El País in 2013 when she agreed to tell her story.

Larissa Arroyo, human rights lawyer and activist, accompanied Aurora to the medical center to solicit the end of the pregnancy. The doctor indicated that that was not permitted. When Article 121 was discussed, the doctor’s answer demonstrated uncertainty about how to apply it, the lawyer says.

“The doctor was very vehement in saying that [abortion] would not be permitted. When I asked about the Penal Code, what he said was: I don’t know, ask my boss,” Arroyo said. Semanario Universidad tried to speak directly with Aurora, but her lawyer indicated that she is not willing to speak further about the topic.

For Sylvia Mesa, a psychologist at the Women’s Investigation Studies Center (CIEM), “the woman is tortured for no reason. No one takes into consideration what [denial of abortion] implies in terms of psychological and physical suffering in that situation.”

Aurora’s case is being discussed in the Inter-American Human Rights Commission and has sparked efforts in Costa Rica to create a norm that regulates the application of the Article 121, given that the process for therapeutic abortion varies from one health center to the other. Due to that, “sometimes it’s a matter of luck if they access it or not,” Arroyo says.

Some hospitals, for example, refer their cases to their bioethics clinical committees, which fill the void created by the lack of clear regulations. These committees are usually made up of medics from different specialties, nursing and social work professionals, pharmacists and legal advisors, to provide recommendations that lead to a final decision.

Other hospitals gather obstetricians and other specialists if the woman suffers from some dangerous disease. Sometimes the decision is up to one doctor.

“There are no paths. As doctors we have no concrete guidelines… it’s a paperwork procedure that we invent each time it happens,” said Oscar Cerdas, chief of gynecology and obstetrics at the San Juan de Dios Hospital in San José.

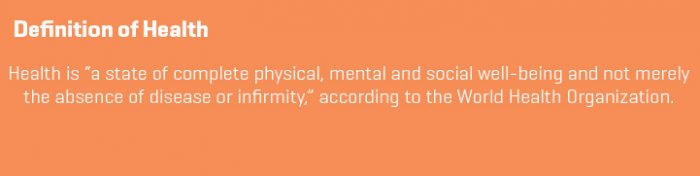

But the biggest obstacle to therapeutic abortion is the interpretation of the law by doctors. Many medical professionals say that Article 121 don’t take the mental and emotional health of the mother into account, and because of that, it only applies when their lives are at risk because of the pregnancy.

The interpretation generally given to “health” is the absence or presence of disease, even though this contradicts the broader World Health Organization (WHO) definition, which took effect in 1948 and was ratified by Costa Rica. Howevr, the mental aspect of health is not taken into account in this usage.

Allan Varela, chief of the Caja’s Health Services Unit, says that the country doesn’t allow abortions due to malformations in the fetus that are incompatible with the life. However, those who defend cases such as Aurora’s say that the request for abortion in such cases is based on the need to protect the physical and mental well-being of the mother.

The obstetrician Raimundo Riggioni, who worked in various Costa Rican hospitals and is now retired, says that there is a massive lack of knowledge of the topic within the medical sector, especially the legal aspect. This causes even more obstacles to abortion.

“There are very conservative doctors and very fearful doctors; they fear that for one of these actions they’ll have a legal risk,” Riggioni said.

There are no lawsuits on the record against doctors for carrying out an abortion of this type, given that it must be practiced with the woman’s consent.

Religious beliefs also sneak into maternity rooms when an abortion is needed, as long as the Medics and Surgeons College supports health professionals’ right to a conscientious objection to performing any medical procedure.

Some obstetricians consulted said they would agree to perform therapeutic abortions in circumstances that seriously affect a woman’s emotional health, as well as when the fetus suffers congenital malformations incompatible with life outside the womb and the mother does not desire to continue with the pregnancy. They’d be in agreement – but only if they are guaranteed legal security.

These sources even agreed that Aurora and A.N. (a similar case that was revealed 10 years ago) needed an abortion because they were high-risk cases, but that fear of legal and social consequences stop their abortions from proceeding.

Stay tuned for Part II in this series from Semanario Universidad, in translation at The Tico Times.