While recently perusing Facebook I noticed an upcoming event that piqued my attention: a tour of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Costa Rica, organized by a group called Chepecletas. All my life, I had yearned to tour a Masonic Lodge and learn more about the secretive brotherhood. On the tour, we would gain access to the Masonic Lodge, temple, and museum — a real insider’s peek at the inner workings of Freemasonry.

Formed in 2010, Chepecletas started offering unique ways to experience and learn about San José, giving participants the benefit of strength in numbers in a city you might not want to explore alone. As you may know, “Chepe” is the endearing and colloquial term used to describe San José; the expression is derived from the common nickname given to men named José.

Being able to traverse Chepe sans car allows one to get to know the city in a more intimate and personal fashion, and Chepecletas feels it is the only way participants can truly enjoy all the hidden treasures San José has to offer.

We arrived on a Saturday in Parque España for a 9:30 tour. After registering more than 40 participants and partaking in a short icebreaker, we took off for the Escuela Metálica at a little after 10. The Escuela Metálica, formally called La Escuela Buenaventura Corrales, is a fascinating building acquired by Costa Rica from Belgium in 1890, shipped in pieces and assembled in place over the course of six years.

Because of the materials and Costa Rica’s warm tropical climate, there was a widespread fear that the school would be a veritable oven for the students as it heated up in the midday sun.

This turned out not to be the case, as the double insulated walls and tubes in the ceiling helped keep the structure cool. Much of the construction material was solid iron, the likes of which had been used to build the Eiffel Tower in 1889 and the Statue of Liberty a few years prior. Buenaventura Corrales thus became the first metallic building in Central America.

We made our way around the corner to a red brick wall with an exotic front door decorated with hand-crafted tiles depicting the saga of Don Quixote. This was the house of writer Don Mario González Feo, who was so enchanted with the tale that his friend, ex-Minister of Culture Guido Sáenz, painted for him 15 beautiful scenes from the epic literary piece. The other side of the building is decorated with “concherías”, as they are called, written by Aquileo Echeverría, representing typical idioms and poems about everyday Costa Rican life.

As the sun began to occasionally peek out from behind the clouds, we make our way from Barrio Amón to Barrio Otoya, stopping at the Casa Amarilla (Yellow House) to admire a piece of the Berlin Wall. Costa Rica is one of only three Latin American countries to have been given a piece of the historic wall — yet another significant slice of history sitting right here in the heart of the city.

We briefly passed the location of the first electrical plant in Costa Rica, which opened on August 9, 1884, oddly enough making San José the third city in the world, after New York and Paris, to have public electricity.

Winding our way through Barrio Otoya, we ended our jaunt with a colorful passage of graffiti-style murals by some of Costa Rica’s most talented artists, every crevice and corner bursting with vibrant original street art.

From the exuberant, we arrived at the drab. Our final destination was a tall, muted blue building jutting out at the corner to greet us. Were it not for the sign, one might mistake it for another insignificant slab of concrete erected in the neighborhood. It is no coincidence that the Freemasons Lodge didn’t hold up to any of my macabre or magnificent expectations; this is in part due to the moral code of the Masons, a humble and modest order that saw no need to build elaborate, ostentatious temples.

Many of the masterpieces made by Masons are, instead, government buildings and public spaces. Masons are said to have played a key role in buiding the spectacular National Theater; one brother revealed to us that upon entering the theater one need only take three steps inside and turn around to see the visual beacon of the Masonic Lodge directly within sight.

Freemasonry was introduced in Costa Rica by a Roman Catholic priest named Francisco Calvo, and the first lodge was completed in 1865. Masons played a surprising role in the history of Costa Rica, with 14 presidents listed as known Masonic brothers, along with many of the ministers, officials and family members that surrounded them. In a country plagued by nepotism, citizens sometimes felt manipulated by a shrouded ruling class, leading to the pursuit and persecution of many Freemasons throughout their formative years in Costa Rica.

In spite of what conspiracy theorists hypothesize about Masons, the brothers are as passionate as they are secretive about their benevolent efforts, and they meet once a week for four hours of Masonic “work.” What that “work” entails is a mystery, as when I asked the brothers if he could describe some of the Masonic rituals, he said, “What the right hand does, the left hand doesn’t know about.”

The brother who so kindly declined to answer my question went on to say that the Masons’ philanthropic acts were something to be carried out and not discussed, as altruism should be the foremost motivator in any underground humanitarian association. The brothers hope to serve as instruments spreading good throughout the community and world from an undisclosed location.

The basic symbols of Freemasonry serve to explain the values they espouse. The square represents direction, a tool to mediate one’s actions, and the compass is a moral guide to one’s consciousness. The sacred book, which is not limited to any one religion, is used by the Masons to swear an oath to uphold their duties. The G on the Freemason logo represents God, the all-seeing higher power by which a Mason is ultimately judged.

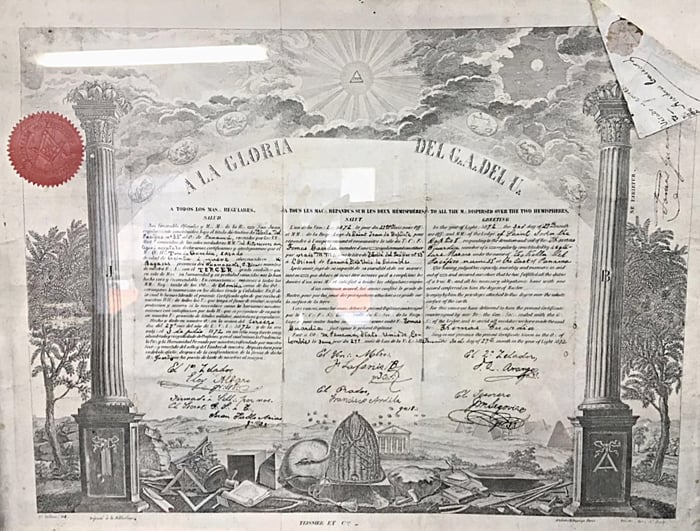

Escorted from room to room, under the ever-present and vigilant eye, we were allowed access to a Masonic museum filled with medals, certificates and oddities. These included the funeral mask of the priest Bernardo Augusto Thiel; a letter written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1779 requesting admission to the brotherhood; and a certificate issued to ex-President José María Castro Madriz instating him to the highest Masonic post of Grand Master.

The tour came to a close in the temple, the most ornate room in the lodge, where the walls were decorated with signs of the zodiac, various idols and props, and an eye staring down at us from the ceiling overlooking some kind of altar.

We were seated in the long hall lined with chairs, featuring on either end two larger, more embellished seats, seemingly reserved for higher officials. We had been assured by our guides that we would be free to ask the brothers anything, but their answers left much to be desired, letting us see, but never know exactly what goes on in a Masonic Lodge.

We headed back to the car around 1 o’clock, happy the tour had come to a close considering the now sweltering heat and growing hunger. One of the reasons that Chepecletas prefers to conduct its tours solely on foot or bike is to reduce the emissions that already choke the vicinity of downtown San José.

When asked about the inspiration behind Chepecletas, director Roberto Guzmán Fernández said its main mission was to “generate love and pride for the city, drawing activity into public spaces around San José, all the while getting participants to leave their cars at home.”

He went on to say, “I think that the cultural activities found around the city are increasingly rich and diverse. They allow us to spend our leisure time stimulating our creativity and expanding our knowledge and thusly, worldview.”

It is an admirable task, motivating people to learn about their surroundings, especially when it involves hoofing it around in temperatures best experienced at the beach. In a country well-known for activities outside its urban center, downtown San José is gaining popularity thanks to groups like Chepecletas that inspire people to get up, get out and get to know their city.

Contact the author at vieandrose@gmail.com.