SAN JOSÉ — Just a few months ago, people in Golfito would smirk when asked about the big marina that was supposed to be built here, saying the project was all talk and no action and had been stalled for years.

Those days are gone.

Golfito Marina Village has the plans, the permits and the plata to proceed with this $42 million megaproject, and construction is happening so fast that Phase I is expected to open by November.

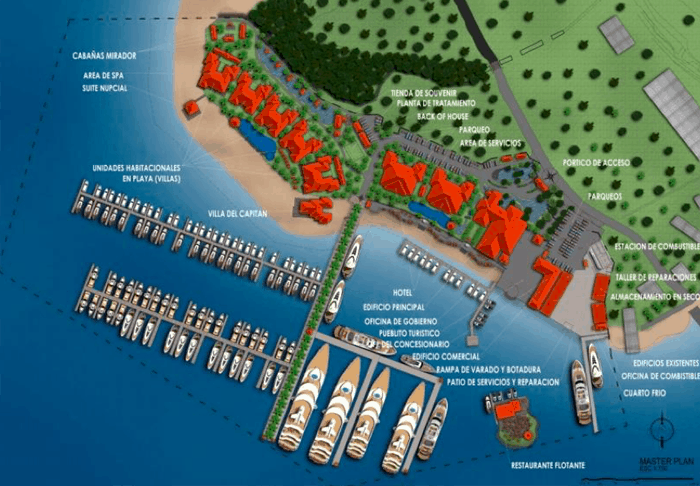

It will have a 50-slip marina, service yard, fuel dock, sewage treatment plant, and a 400-square-meter Fisherman’s Village commercial area. When completed, by 2019, the marina will have 132 slips, a 54-room hotel and 57 villas.

This marina will be the Golfo Dulce’s biggest development ever, rivaled only by another planned marina across the gulf, at Crocodile Bay in Puerto Jiménez. Together, these projects could transform the Golfo Dulce from a sleepy backwater to the playground of billionaires with 350-foot “gigayachts.”

“It’s not a lot of vertical construction, and the docks, it’s like a Lego,” said Pedro Abdalla Slon, 54, project manager and chief architect of the Golfito Marina, referring to Phase I as he outlined the vision in a presentation for The Tico Times at his office in Sabana Norte.

“It comes in, and you just put it together, and we’re working really hard and really fast to get it ready because we can’t lose this high season,” he said.

Abdalla, born in Costa Rica to parents from Lebanon, said the project stalled seven years ago because of the global recession, when banks stopped lending money.

But three years ago, the marina got a new lease on life.

“The project got smaller,” he said. “The size was reduced to make it more realistic to the global market after the crisis. So that allowed us to lower the cost of Phase I from $30 million to $12 million, $11 million.”

In July 2015, the project was given final approval by the government, with all the permits needed to proceed. In December, the money came through with $7.5 million from Banco Nacional and $3 million from the partners on the project.

The projected cost of all three phases is officially $41.8 million, though Abdalla said $55 million is probably a more realistic figure.

The three phases

Here’s the plan, according to slides shown by Abdalla that reflect an ever-evolving design and cost.

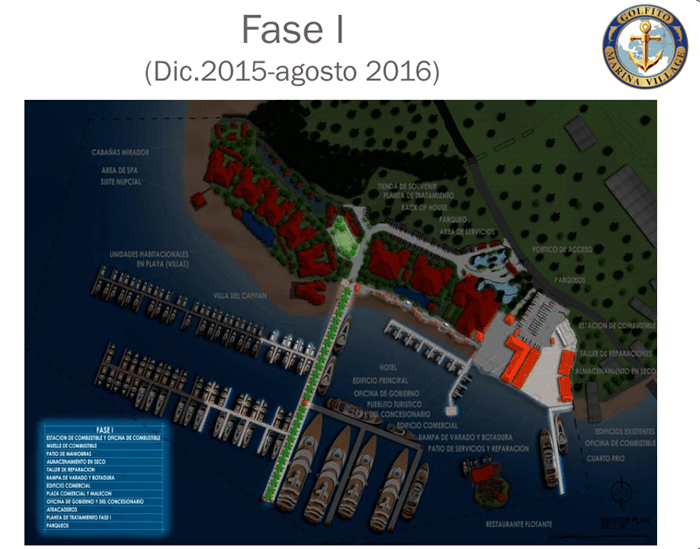

Phase I, to be completed by November 2016 at a cost of $9.9 million, will have 50 boat slips, a 400-square-meter commercial area, a sewage treatment plant, a fueling dock, dry storage for 13 boats and parking for 26 vehicles.

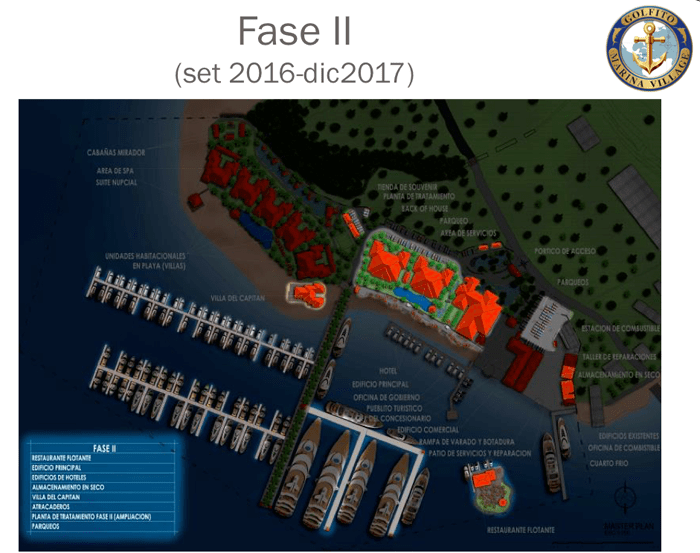

Phase II, to be completed by December 2017 at a cost of $16.3 million, will have 132 slips, a 54-room hotel, an 1,100-square-meter floating restaurant, a 1,500-square-meter commercial area, dry storage for 34 boats and parking for 68 vehicles.

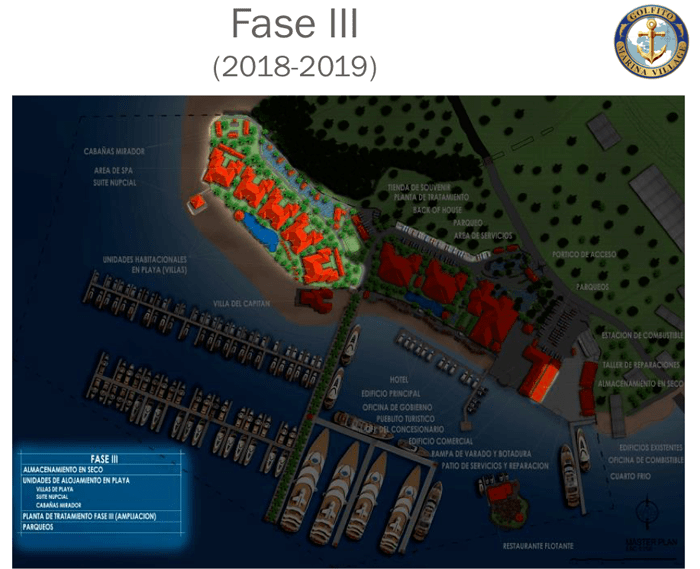

Phase III, to be completed by 2019 at a cost of $15.7 million, will have 57 villas, dry storage for 41 boats, a spa and souvenir store, and parking for 35 vehicles.

“And if we have more demand, we can increase the concession,” Abdalla said. “We have the space.”

Abdalla, 54, has been working on this project for 10 years. And it seems that victory is finally within reach.

Any opposition?

Just across the Golfo Dulce, roughly a 30-minute ferry ride away, Puerto Jiménez has been a hotbed of opposition to Crocodile Bay’s plans to build a 115-slip marina, a 74-room hotel and 50 private residences.

Likewise in Pavones, the world-class surfing capital south of Golfito, the Pavones Point condominium complex now under construction remains fiercely controversial.

So what about the Golfito Marina Village, a project similar in size and scope to Crocodile Bay?

“Seven years ago, some environmental people, you know, as usual, tried to fight against that, but, I mean, we have all the approvals,” Abdalla said.

The owners of Crocodile Bay and Pavones Point also say they have “all the approvals,” but that hasn’t won over the vocal opposition.

Abdalla said hardcore environmentalists will often start a fight “because they don’t know about projects like this,” and “because they have money to fight.”

“Now the people believe in the project,” he said. “So now they will fight against the people who want to stop this, because now they have jobs.”

How many jobs?

He said the current construction project employs 100 people, 80 of them from the Golfito area. “It’s a commitment that we have with the municipality,” he said, that 80 percent of the jobs go to locals.

In the long run, he said, he expects the marina to create 400 jobs directly and 800 or more indirectly.

What do the locals think?

Hans Mora, a 27-year-old businessman who lives in the area and is involved in the Pavones Point development, said, “I’m not opposed to the marina or that type of development. As far as I know, with the people I’ve talked to about this, I haven’t heard bad comments, I haven’t heard anybody who’s against it.”

Mora said he is aware of the environmental controversy over the Crocodile Bay Marina, and of the primarily foreign opposition to Pavones Point, but as for the marina in Golfito, he said, “I see it as a good thing for the Southern Zone.”

“As far as I know, the Golfito Marina has no opposition, no organized group,” he said. Referring to Crocodile Bay, Pavones Point and Golfito Marina, he said, “I understand that all the projects have all the permits they need and all the government permissions and requirements, so they have nothing to hide ….

“With most people that I’ve talked to in Golfito about this project, everybody is in favor and they’ve been waiting a long time for this project to be developed.”

Mora said not long ago there was talk of closing the duty-free zone (“el depósito libre”) in Golfio and opening one on the Caribbean coast in Limón.

“The depósito opened in Golfito because the banana company left; otherwise it would be a ghost town,” he said. “The only other economic activity is fishing. There’s a lot of little cabinas, little restaurants, that survive on local tourism, Tico tourism, from people who come to buy things at the duty-free zone.”

But what if a duty-free zone opened in Limón, two or three hours from San José? “Who’s going to go to Golfito?” he asked.

“It gives people a lot of tranquility to be able to seek another kind of work, which would be this marina,” he said. Every boat that comes to this harbor will generate multiple jobs, he said, that can feed families.

Katie Duncan, a longtime Golfito resident who runs a property management and vacation rental company called Land Sea Services, echoed Mora’s assessment that this project is welcome here.

“Honestly, I do not know of anyone seriously opposed to the project,” she said. “There have been prior concerns about potential issues such as sewage treatment plans, traffic hazards and congestion issues along our limited one-road artery through town.

“There has been discussion over the potential of costly damage to our roads by their movement of heavy equipment or environmental damages by overconsumption of sand from local rivers. There are worries that a project that is too dense or architecturally ‘modern’ [and doesn’t] fit in with our low-key ‘pura vida’ style could compromise the coveted laid-back feel Golfito is known for. … But I have not seen any indication yet that the current project underway isn’t prepared to handle the issues and damages they create satisfactorily….

“Most of my informed and forward-thinking neighbors and the community business persons I associate with believe as I do. I feel an operational, well-run, full-service marina or a multiple of them along our bay is what this town needs to become vibrant again. In reality, marinas and related support businesses and tourism services that will follow are economically and environmentally our best hope for a sustainable and viable economic base.”

A natural advantage

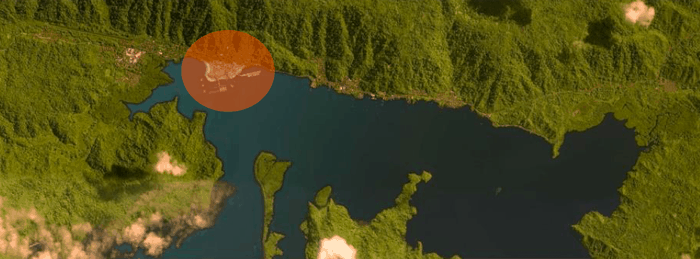

Abdalla said Golfito Bay is virtually the perfect place for a project like this because there are no waves and the water is 10 meters deep. “It’s a gulf within a gulf,” he said.

Whereas Crocodile Bay, which is in more open water, has to build a breakwater, the Golfito Marina does not. That means that no special maneuvering is needed for 350-foot superyachts to pull in and dock.

“This side will be for the gigayacht people,” he said. “You know, they want to be separate. They don’t like the millionaires; they are billionaires.” Everyone laughed.

According to the U.K.’s Daily Mail, a yacht being built last year, the Double Century, would be the world’s largest, at 656 feet long and cost $770 million. It will eclipse the 590-foot Azzam, owned by the head of the United Arab Emirates, and will dwarf the 452-foot Rising Sun, owned by Oracle founder Larry Ellison, currently the 7th-richest person in the world.

Abdalla said this will be one of the few places in the world where gigantic yachts can easily dock. And their wealthy owners can fly their private jets directly into the Golfito airport, bypassing San José — at least most of them.

“Not 100 percent of the planes can land, but 80 to 85 percent of private jets can land there, and we have already in Golfito immigration and customs,” he said. “We have to put some lights and some minimum things, but if you have customs and immigration, you’re done.”

What Maritime Zone?

The all-important Maritime Zone, which makes it impossible for anyone to own property within 200 meters of the ocean, is oddly not a factor in the Golfito calculus.

“We have no Maritime Zone in Golfito,” Abdalla said. “It’s a coastal city.” He said there are five places in the country where there is no Maritime Zone restricting beach ownership: Limón, Puntarenas, Jacó, Quepos and Golfito.

So anyone can own beachfront property in Golfito. Anywhere outside these five towns, the best you can get is a concession that allows you to operate a business on a beach for a given number of years, but the beach belongs to the people.

Golfito Marina, however, does operate as a concession. Why? Because seven years ago, before the global economy crashed, it created a 3-hectare landfill in what was formerly the ocean, with 13 hectares on land. In 2005, the marina was granted a 35-year concession, which it will have to renew in 2040 for 10 years, and every 10 years after that.

“So when you buy a villa here, you buy really like a membership,” Abdalla said. “Legally, it’s called a private residential club.”

By the way, the 1-, 2- and 3-bedroom villas will cost $350,000 to $800,000 for something you will not technically own. So start saving now.

Too much competition?

Asked whether the opening of both the Crocodile Bay Marina and the Golfito Marina would create a glut of yacht slips that would exceed demand, Abdalla said absolutely not.

“We are happy that another marina is coming,” Abdalla said. “Because that means that the area is going up, it’s not just one marina, it’s a new area coming. We’re going to have like a hub of marinas, because too many people are interested in Costa Rica.”

Contact Karl Kahler at kkahler@ticotimes.net.