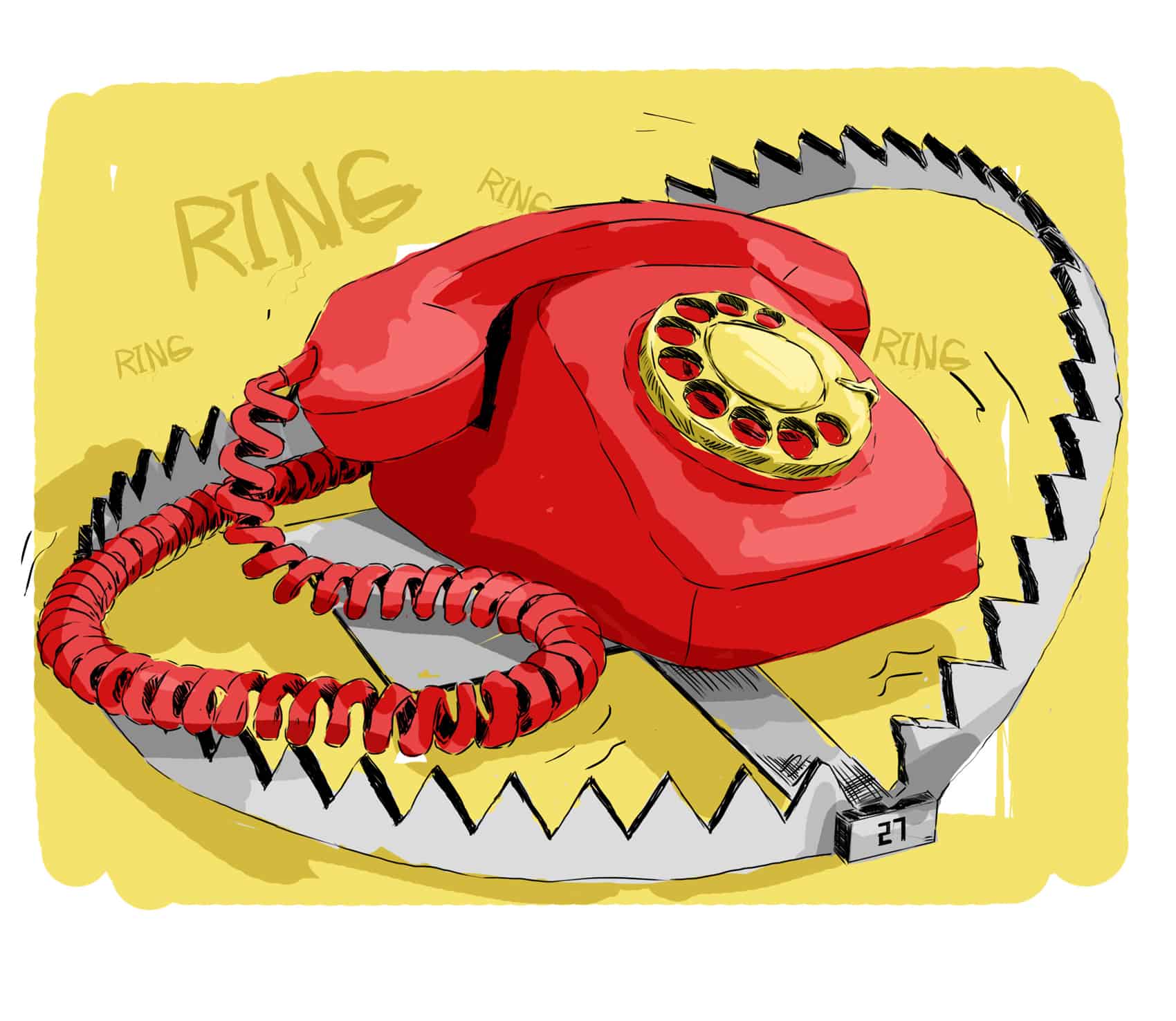

A New York area code flashed on the caller ID when Lita picked up the phone in April 2015. The man on the line introduced himself as Vince Anderson, a customs agent at John F. Kennedy International Airport. He said he had a package waiting for Lita.

Lita, who lives in Houston, Texas, found this a bit odd. She wasn’t expecting any package. But she decided to follow Anderson’s instructions anyway.

Anderson told her to contact Jason Mann, an underwriter for the Lloyds of London insurance company, to pay for the delivery insurance. When Lita, an 81-year-old retired social worker and mother of three, called Mann, he was friendly and earnest, she later said. He congratulated her on winning a Reader’s Digest sweepstakes worth $375,000.

She was taken aback but, understandably, enchanted by the possibility that such a large windfall might actually be hers — and without even trying. She hadn’t entered any contest that she was aware of.

The promise of that $375,000 prize would lure her down an increasingly twisted, confounding path, eventually costing her more — much more — than she could have ever imagined.

“I believed that people are good but I went wrong,” said Lita, who asked The Tico Times not to use her full name because her family is unaware of her missteps and because her ordeal is not yet over.

An expensive mistake

“How come I didn’t know I had won?” Lita asked Mann that day on the phone, nearly a year ago. Mann said that she likely got the notification in the mail and didn’t realize what it was.

She thought about this. She got so much junk mail and had been shredding reams worth of it. It was completely possible that she had, in fact, received a letter notifying her that she had won and simply tossed it in with the unsolicited magazine and credit card offers.

Missing that letter, though, was an expensive mistake, Mann told her. If she had made the deadline to collect her prize, she only would’ve had to pay $750 in delivery insurance, but since she missed it, collecting would be a bit more complicated, Mann explained.

She also had to pay taxes on the prize, he said, and while normally they would’ve been taken out automatically, because she was claiming the prize money after the deadline had passed, she would need to pay the taxes upfront.

The bill would be $18,000, Mann told her.

Lita is not a rich woman, and normally this would have been a lot of money for this retired Texas Commission for the Blind social worker. But as chance would have it, at this particular moment in her life, she did have $18,000. In fact, she had a lot more than that in the bank.

Lita is originally from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, an island nation in the Caribbean. She hasn’t lived there since 1982 but still has her warm Caribbean accent. After she retired in 2004, Lita started spending more time in St. Vincent with her aging mother.

When her mother passed away in 2014, Lita inherited the family home and decided to sell the property. Lita said she sold it for roughly $300,000 and kept most of the money from the sale in a bank account in St. Vincent. Lita had simple plans for the money: pay off her mortgage, replace her car and put the rest toward her four grandchildren’s education.

With $300,000 sitting in a bank in St. Vincent, $18,000 in taxes to collect another $375,000 seemed like a bargain. Lita could do everything she hoped and more with so much money. She decided to go for it.

Mann told her the prize money was being held in an account in Costa Rica and therefore it would be easier to route fees and taxes through the Lloyds of London office there. He also said she would need a lawyer to oversee the process and introduced Lita by email to Keith Holmes, who Mann said was a financial lawyer based in New York.

When Lita told one of her daughters about the offer, her daughter told her it sounded like a scam.

“She’s like my other daughters, very skeptical,” Lita said. “I told her that she needed to trust people.” After all, there was the man from JFK and when she called Mann he answered the phone saying he was with Lloyds of London. And there was the lawyer, Holmes, too. There were so many people involved, seemingly from unrelated institutions, how could it be a scam?

“It had to be genuine,” Lita thought.

On April 16, 2015, she followed Mann’s instructions and, without telling anyone in her family, sent the first payment of $9,375 to a Costa Rican bank account tied to a company called Eventmark Internacional, S.A.

‘Your luck I wish I had’

It turned out that $18,000 was just the beginning. After she paid the supposed taxes, which Mann told her were imposed by the state of Texas on all sweepstakes winnings, Lita got more good news from Mann.

She was told that her $375,000 was actually the second place Reader’s Digest prize, and since the first place winner couldn’t pay the taxes and fees on that prize — worth $825,000 — Lita was entitled to the first place prize, too.

Her winnings now totaled $1.2 million, Mann told her.

But with that jackpot came more taxes. The previous winner had already paid the state taxes on the prize, she was told. All she would need to do now was pay the remaining federal taxes — $208,000 — before she could collect.

Lita shrugged to herself. “If that’s what I have to do, I guess that’s what I have to do,” she thought.

She started making several transfers a week from the St. Vincent bank account that held the money from the sale of her mother’s home to bank accounts at Banco de Costa Rica, Banco Agrícola de Cartago and Banco Nacional in the name of Eventmark and another company called Celestial Transa, S.A.

By April 29, 2015, had transferred more than $37,000.

By May 23, 2015, Lita had transferred more than $75,700.

Holmes, the supposed lawyer, wrote her an email dated May 27, 2015, congratulating her on the jackpot. “Your luck I wish I had as again I have only seen this happen once since I have been working on these types of issues with Lloyds.”

By June 15, 2015, Lita had transferred a total of $120,401.

As weeks turned into months with no prize, and the money flowing out of Lita’s account rose into six-digit figures, her anxiety grew. She had already given up nearly half the money from the sale of her mother’s home.

When Mann told her she had won the first prize jackpot, he had said that the previous winner lost the prize because he couldn’t pay the taxes. What if she had spent all this money only to come up short? Lita was increasingly worried that something was wrong but to stop paying would be to admit that she had been scammed – and to give up a potential fortune.

“I thought, ‘I can’t turn back now,’” she said, “‘I’ve paid too much already.'”

Sensing that Lita was getting skittish, Mann said that Lloyds of London could help her complete the payments with “financial aid.”

In a June 2015 email to Lita, Mann said Lloyds of London would lend her $150,000 of the $178,000 in taxes still owed if she agreed to pay the company back after she claimed her million-plus prize. Mann stressed in the same email that she would be expected to pay back the loan.

“I spoke with Keith today in length and he told me that it is very important that you pay back the financial aid that you have been given,” Mann wrote. “He said that you gave him your word and he believes in you as I do.”

Mann told Lita she needed to pay the remaining $28,000 not covered by the supposed financial aid quickly to “avoid further delays.”

Lita also wanted to avoid further delays. “I am also anxious to have this matter finalized,” she wrote Mann in an email dated July 2, 2015.

As her doubts mounted so did her elusive prize money. Jason Mann forwarded Lita a letter dated Sept. 29, 2015 with the IRS’s eagle logo on the letterhead. It was addressed to Mann from Harry Ferguson, Inspector General for Tax Administration. The letter explained that Lita was eligible to receive another $67,485 thanks to interest accrued by the prize money in an offshore account created by Eventmark.

Her winnings were now supposedly $1,267,485.

By the end of September Lita had transferred nearly $178,000.

“Once the tax is paid and initiated, the wire to your client’s account will be approved within 48 hours,” the letter from Ferguson said. “Thank you Jason, I appreciate your professionalism!”

In October, around the time she got the surprise boost in her prize, Lita got an unexpected phone call from a man who said he was with the Federal Trade Commission. The man introduced himself as Richard Smith and told Lita that she might be the victim of a scam. He offered to help her retrieve the money she had sent to Costa Rica.

Lita was skeptical. How did Smith know she had won a sweepstakes or that she had sent money to Costa Rica? Lita didn’t call Smith back and soon he stopped calling.

Meanwhile, Lita continued to transfer money to the Costa Rican bank accounts specified by Mann. As she supposedly approached the finish line for paying off the taxes, there was another snag. Mann said that the Costa Rican bank holding the prize money would not send the money to her U.S. bank account.

Lita got an email from a man named Eduardo Sáenz Guerrero who said he was a Costa Rican lawyer working with Eventmark on her behalf. He said she would have to open a Costa Rican bank account — at Banco de Costa Rica — and establish an investment account with Eventmark in order to collect the prize money. That would cost her an additional $24,251, Sáenz wrote.

Again, Mann offered Lita “financial assistance” to cover half the amount.

“We would like to thank Jason Mann,” Sáenz said in the same email, “whose participation has positively affected innumerable negotiations and people throughout the world.”

Lita sent another $9,985 to an Eventmark account on Dec. 17, 2015. Five days later, Mann stopped answering her emails.

Lita was already anxious about how much money she had sent to Costa Rica and the sudden silence from Mann and the supposed New York lawyer, Holmes — people who had been communicating with her almost daily for months — unsettled her.

The Lloyds of London Scam

In January, Lita stumbled upon an article from The Tico Times published on June 1, 2015 about a series of telemarketing scams operated by U.S. citizens in Costa Rica that defrauded older U.S. residents of millions of dollars between 2002 and 2013. Call centers based in Costa Rica known as “boiler rooms” would call unsuspecting older U.S. residents and try to convince them that they had won a sweepstakes prize.

To claim the prize, victims were told that they would have to pay an insurance fee or taxes, expenses that would spin out into the hundreds of thousands of dollars in some cases. Boiler-room callers would commonly tell victims they worked for the famous English insurer, Lloyd’s of London, which is spelled with an apostrophe, not “Lloyds” as many scammers write it.

The perpetrators of the Lloyds of London scam in the early 2000s are still being dealt prison sentences after their convictions. The latest was Geoffrey Alexander Ramer. The 36-year-old dual U.S.-Costa Rican citizen was sentenced to nine years in prison on March 15 for his role in a $1.88 million sweepstakes scam operated from Costa Rica. The scam targeted hundreds of elderly U.S. residents between 2008 and 2013, according to a Justice Department news release.

Lita wrote an email to The Tico Times saying that her experience was very similar to the Lloyds of London scam. “I believe I may have been a victim,” she said.

Anatomy of a scam

Between April 2015 and December 2015, Lita sent $211,981 to several Costa Rican bank accounts supposedly registered to Eventmark and Celestial Transa, and to a handful of individuals posing as employees of Lloyds of London and several U.S. government agencies.

Lita is not alone. The Better Business Bureau’s Scam Tracker reported nearly 1,400 sweepstakes scam complaints across the U.S. during the last 12 months.

“I’m not foolish,” Lita said. “It all sounded so credible. I had no idea it could be a scam.”

Fraudsters are very convincing on the phone, but according to AARP, there are several red flags Lita should have looked for to protect herself, namely if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Other warning signs are plain in Lita’s story, too: offers of big money prizes for contests that one never entered, and pressure to act fast.

Listen to a voicemail Lita received from Jason Mann pressuring her to continue sending money.

One of the ways scams operate is by using the names of government agencies or private companies that people would recognize, like Lloyd’s of London, to lend credibility to the perpetrators’ story. Lita said that she was familiar with the Lloyd’s of London name but she never Googled the phrase “Lloyds of London Costa Rica.”

If she had, she would have gotten results that included a fraud warning from the FBI and several news stories dating back to 2010 about sweepstakes scams.

Chris Baker, a financial crime officer with Lloyd’s of London, confirmed to The Tico Times in an email that the company does not have an office in Costa Rica and it has never employed anyone named Jason Mann. A 2011 consumer alert from the company on sweepstakes and lottery scams states that Lloyd’s of London underwriters “would never contact any person directly asking them to pay a premium to collect any ‘alleged’ winnings.”

The names of the lawyers supposedly helping Lita were also made up. A quick search of the New York Bar Association’s website would have shown that Keith Holmes, the supposed financial lawyer in New York, is not registered to practice law there.

Eduardo Sáenz Guerrero, the supposed Eventmark lawyer, is not registered with the Costa Rican Attorneys Association and that name does not appear in public record searches.

The scam artists similarly preyed on Lita’s trust with the forwarded letter on IRS stationary. The IRS does have an employee named Harry Ferguson, but he never penned a letter to Lita.

The letter supposedly from “Inspector General Harry Ferguson” used a Brooklyn, New York address. But the real Ferguson works as a tax examiner in Cincinnati, Ohio, according to Kevin Smith, an IRS media relations representative. The real Inspector General, whose actual title is “Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration,” is J. Russell George.

Smith said there would be no reason for Ferguson to send a letter requesting or advising a private citizen like Lita on sweepstakes winnings.

According to an IRS statement on scams, the IRS does not send “unsolicited email, text messages or use social media to discuss your personal tax issue.”

Another telltale sign of a scam, according to AARP, is that once a victim agrees to send money, requests for more money don’t stop.

After Lita agreed to pay the initial $18,000, the scammers pressured her to start making payments quickly, and once she had paid tens of thousands of dollars, told her that she would lose that money and her prize if she didn’t complete the full payment of phoney taxes. Lita found herself in a vicious cycle where the more she sent, the more aggressively the scammers pursued her.

Lita thought she was sending money to real companies in Costa Rica affiliated with Reader’s Digest and Lloyd’s of London, but the corporations were shells that lacked even a physical address.

A list of bank transfers provided by Lita to The Tico Times showed that she sent the majority of the money to bank accounts in Costa Rica in the name of two corporations: Eventmark Internacional, S.A. and Celestial Transa, S.A.

“S.A.” stands for sociedad anónima, a corporation in which the shareholders are anonymous.

Celestial Transa, S.A. did not appear in a public records search of registered corporations in Costa Rica. The address provided to Lita for the company is actually the address of the Banco de Costa Rica in downtown San José.

Eventmark Internacional, S.A. is a registered company. According to a public records search, the corporation is listed as a “consultancy for marketing and publicity, business, industry, acquiring all kinds of goods and real estate, personal and real rights, granting guarantees on behalf of partners and third parties as a fiduciary.” The firm is not registered with the Costa Rican Social Security System, suggesting either that it has no employees or is employing them illegally.

The Tico Times visited two physical addresses provided for Eventmark on its bank accounts with Banco de Costa Rica and Banco Agrícola de Cartago near the Subway restaurant on Paseo Colón and the Comptroller General’s Office in Sabana Sur. The address given near Paseo Colón was a vacant storefront that a neighboring business owner said hadn’t been occupied in two years.

There are several call centers located in Sabana Sur but none near the address listed for Eventmark Internacional had any business registered there under that name. The recent U.S. investigation that has netted numerous scammers posing as Lloyd’s of London representatives found that the scam was largely run out of Costa Rican call centers.

Along with the fake names and addresses, the amounts of the wire transfers are suspicious. A list of bank transfers Lita provided to The Tico Times showed that none of the transfers from her bank accounts in St. Vincent and the United States to the accounts in Costa Rica exceeded $10,000, which is the threshold for additional scrutiny by financial intelligence authorities. The majority of the transfers were just under this official red flag, including one to Eventmark for $9,995.

According to a Costa Rican antiterrorism and anti-drug trafficking law, any financial transfers equal to or greater than $10,000 must be reported to the Costa Rican Drug Institute and require additional oversight from banking authorities.

Lita said that she could not move more than $10,000 a day out of her St. Vincent bank account without being at the bank in person.

One email dated June 22, 2015 between Mann and Lita asked her to divide a $28,000 payment into three separate ones. Intentionally breaking up larger transactions into smaller ones to avoid scrutiny is known as structuring or “smurfing” — the same term used to describe how meth cooks avoid individual buying limits of pseudoephedrine. Structuring financial transfers is punishable by a fine and up to five years in prison in the United States.

Even if Lita had realized sooner that she had been the victim of a scam, bringing the scammers to justice could be complicated. Juan José Rojas, chief financial crimes investigator for the Judicial Investigation Police, told The Tico Times that telemarketing scams like the one Lita fell for are common in Costa Rica but difficult to investigate because the victims often live in other countries and never file criminal complaints.

At the time of this publication, Lita had not filed a criminal complaint in Costa Rica.

Rojas said that the international nature of these scams could involve three or more countries, depending on where the victims and fraudsters are and the bank accounts used by criminals. Legally speaking, the crime is committed in the country where the money is taken out of the bank.

Rojas said it was highly unlikely that someone other than the individuals or corporations listed on the bank accounts to which Lita deposited money had opened the accounts. If so, it would have required notary fraud.

Regardless, the company or individual listed as the beneficiary of an account is legally responsible for any illicit funds that enter or are removed from that account, Rojas said.

‘Hell no, I’m not going to do it!’

Lita finally reported the suspected fraud to the FBI in Houston in January. She said an official took down the details of her story but told her that the FBI typically does not work individual cases.

Frustrated, she reached out to the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, but she could not reach Richard Smith, the FTC official who had previously contacted her.

In February, Lita got a call from a man who identified himself as Richard Gold with the FTC. Gold told her that he had been assigned to her case, but by that point, Lita was wary of strangers offering help.

“How can I be sure you are who you say you are?” she asked him. Gold told her she could look him up on the FTC’s online directory. She did and his name was listed on the website.

Upon Gold’s request, Lita sent him a list of all the transfers she had sent to Eventmark and others who could have been involved in the scam. Gold gave her his direct number and said she should call him there, not the one publicly listed on the website.

Gold told Lita he couldn’t guarantee that he would get her money back but he would try.

After Lita began communicating with Gold, Jason Mann started calling again. Lita said that she was getting several calls a week from Mann, pleading with her to pay the “last” $3,000.

“He would say, ‘I don’t understand why you won’t pay this last bit, you’re so close,’” she said.

Mann’s calls would try to guilt Lita into paying. “It’s a lot of money out there and you’re not doing your part,” Mann told her in a voicemail recording Lita shared with The Tico Times. “If I don’t hear from you, good luck, because I’m not going to deal with this case anymore.”

Lita said she wanted to call Mann’s bluff and say she knew it was a scam, but thought better of it. She was speaking with the FTC and had reported her case to the FBI. What if by keeping Mann on the line she could help catch him?

During the first week of March, Gold called and said he had found Lita’s money. He said he had spoken with the Costa Rican Embassy in Washington, D.C. and an embassy official there named John Vega said the money was located in a Costa Rican bank.

All Lita had to do, Gold told her, was pay $20,000 in “bank taxes” to recover the several hundred thousand she had lost to the scam.

Suspicious, Lita went to the FTC website again and looked up the publicly listed number for Gold. She called that number instead of the one Gold had said was his direct line.

Richard Gold picked up the phone. He said he had never spoken with Lita before.

This Richard Gold did work for the FTC but his job title was Freedom of Information Act public liaison, not fraud investigator. He said he knew nothing about her case.

Just as Lita thought she had escaped the fraud, it had caught her again. “Hell no, I’m not going to do it!” Lita said to herself, breathless at the idea of giving another $20,000.

Even the supposed embassy official who the fake Gold said had located Lita’s money was a sham. Costa Rican Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Melissa Durán told The Tico Times in an email that no one by the name of John or Jhon Vega works at the Costa Rican Embassy in Washington, D.C.

And it didn’t stop there. Holmes, the supposed lawyer, called Lita in early March offering to fly to Costa Rica and look into her case as independent counsel. Since he would be representing her and not Lloyds of London, he would need the money upfront, he told her. He normally asks for a retainer of $10,000, he said, but he was sure the two of them could work something out.

Lita, however, was done sending money — to Holmes, Mann and everyone else hoping to squeeze another couple grand out of her.

Nearly a year after that first exciting phone call, Lita realized her daughter was probably right. She should be a little less trusting.

Lita knows it might be too late for her to get restitution. But she wants to make sure this scam doesn’t happen to someone else. “I want them caught, whether or not I get my money back,” she said.

Lita still gets several calls a week from Mann, Holmes and, most recently, Vega.

Contact Zach Dyer at zdyer@ticotimes.net