I have long believed that each of us has the right to two countries. The one where we were born, and the other, which we freely choose. The other, for me, will always be Costa Rica. -“First Lady of the Revolution,” Spark Media

I shivered when I heard these words spoken, a calm voice that sprang suddenly from my computer to break the silence of my parents’ house in Maine, where I sat working late at night during a visit home. It was that thrill of recognition you get when you hear, for the first time, the voice of a person whose words you’ve read for many years. More than that, though, it was the thrill you get when you hear words you could so easily have said yourself.

I have a few things in common with the speaker, featured in a trailer for a documentary film I’d stumbled across just then through a friend’s Facebook post. We are both U.S. citizens who came to Costa Rica as young women to see what we could see, assuming ours would be brief visits. (They weren’t.) We both married Costa Rican men and became mothers here.

We both, for vastly different reasons, ended up participating in or witnessing aspects of the presidency, so that we got to know our adopted country from a variety of perspectives. We both know the uncertainty of navigating all of these roles in another country and culture. We both know the balancing act and yearning and long-distance love of this kind of life.

The speaker was, in short, a woman who would have understood without the need for words the exact set of mixed feelings I was nursing right there in my parents’ kitchen, steps from a rocky shore and a cold sea. The comfort that comes from the smell and sound of home, unmistakable even in the hush of night. The desire to read every book on the shelf, memorize every sketch and photo on the walls, stay forever. The craving, nonetheless, for a very different place; for tropical downpours and extra helpings of rice; for the good, the bad and the ugly of Costa Rica.

All of that, we share. But it stops there.

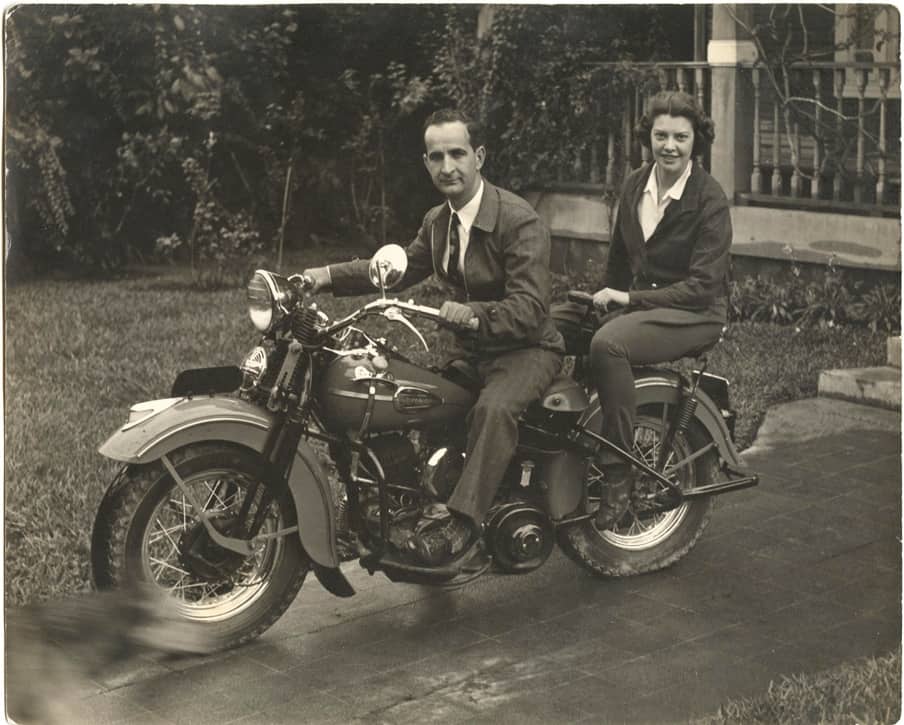

When this woman came to Costa Rica, she took an eight-day boat trip to Limón, not a five-hour plane ride into a sleek international airport. She got to know the country by train and horseback and motorcycle, not in taxis whizzing through roundabouts past mammoth malls selling KFC and Häagen-Dazs. The Costa Rican man she married had no ordinary future ahead of him: he would lead Costa Rica’s 1948 Revolution and become the architect of the country we know today.

In short, the country she met in 1940 had been totally transformed by the time I arrived in 2004. And in many ways, that transformation was set in motion by events in which she herself played a crucial part.

The woman whose voice I was listening to that night was Henrietta Boggs, first wife of José “Pepe” Figueres, the woman who was at his side during his first forays into politics and his exile. She spent part of the revolution scrambling with her young children through the Cerro de la Muerte, or “Hill of Death,” carrying her youngest in her arms over the high, cold, rough terrain to escape enemy fire. Then she became the First Lady of Costa Rica at the age of 29. She is a link to Costa Rica’s watershed moment, and a fascinating bridge between the United States and Costa Rica, though she is all but unknown to many citizens of both countries.

But as I write these words, a team of filmmakers is busy editing a new documentary about Henrietta Boggs to be released later this year, and Henrietta Boggs herself is preparing for the talk she’ll give this week in San José at the TEDx Pura Vida conference. Today, at 97, it seems that the first lady is finally ready for her closeup.

I stood on the deck of the ship which was carrying me to a strange land, and watched the shoreline slowly grow more distant. Waves swished languidly against a rocky promontory, protecting the wharf where banana boats were tied up before a string of warehouses. Overhead, huge billowy clouds pushed by the trade winds piled higher and higher… The driven clouds made me, too, feel as if I were being impelled towards a bewildering new future for which I was unprepared.

-“Married to a Legend” (2008)

I think I first learned about Henrietta Boggs when I came across her memoir by chance in a San José bookstore. I had been in the country for a few years as a reporter and was now working as a presidential aide. I read the blurb on the back, bemused. Don Pepe’s first wife was a gringa? Seriously? What would that have been like? (When The Tico Times published an interview with her shortly thereafter, I learned she had once written a column about her experiences for this paper.)

My parents came for a visit and we read her story together. During that trip, we stayed at a rural lodge near the Nicaraguan border without electricity in the rooms; if you’re night owls, as we are, you’d better have a good book to read by candlelight.

We did. We took turns reading “Married to a Legend” out loud to each other, shaking our heads in near-disbelief as her story unfolded. It reads like a novel: the young traveler meets a mysterious stranger with piercing blue eyes. He proposes during a ride on his beloved Harley Davidson up the Irazú Volcano, and she accepts while gazing into the smoldering crater.

With that fateful decision, she plunges into an adventure she handles with astonishing aplomb and discusses it with the reader quite frankly, as if she were dishing over a bottle of wine.

It’s the kind of thing you couldn’t make up if you tried. It’s also an extraordinary glimpse of history, for several reasons. One, that Costa Rica in general, and San José in particular, have changed at such a dizzying rate since Henrietta’s time living in the country. This makes it utterly fascinating to read even the most basic details.

For example, she attends a fancy expatriate dinner at “a big house at the end of Avenida Colón” with “a wide verandah shaded by stately palms interspersed with coffee and orange trees.” You pore over the details, trying to figure out where it was — probably a giant bank by now.

Or immediately following her marriage to Figueres, the couple heads out to Desamparados to get the horses they’ll ride all the way to his farm in the mountains, La Lucha Sin Fin (“The Endless Struggle”). Desamparados, now a massive expanse of concrete and malls and multiplexes, is, in Henrietta’s time, a tiny outpost in the rain.

I am from New England. If my great-great-great-grandmother appeared before me right now and described the geography of her life, it would be fairly recognizable: the streets, the landmarks, even many of the homes. To read something written by a person who is still alive, describing a city I now know quite well but in a completely different incarnation, is fascinating for that reason alone.

The second reason the story is so unusual is that it’s impossible to overstate the gigantic presence of don Pepe in Costa Rica’s collective consciousness. “Revere” is not quite the right verb for a country as practical as this one, and the leader’s flaws are as widely known as his virtues.

One of the first things I ever heard about Figueres when I began work as a reporter, a story I’d hear again and again in the years to come, was that he was asked what had been done with some funds earmarked for a certain purpose, and said gleefully, “I spent it on candy.” That is: What’s it to you? I’m the president.

But that story is generally told with a smile, sometimes even a certain nostalgia for the unilateral power that the presidency, or at least Figueres, once had. At any rate, it’s generally underpinned by overall admiration for the legendary figure who led an armed uprising following fraudulent elections, who enacted remarkable reforms and then gave up power peacefully (to be elected twice more, serving in 1953-1958 and 1970-1974).

This is the man who took a sledgehammer to the Bella Vista fortress and abolished Costa Rica’s armed forces (Henrietta informs her readers that he sent a crew the day before to loosen the stones to make sure the theatrical gesture would work); who led the governing board that founded Costa Rica’s Second Republic, creating the current Constitution and many of the institutions without which life in modern Costa Rican would be unimaginable; and who founded the National Liberation Party, a pillar of the country’s two-party system for decades and still a driving force in the current multi-party panorama.

In other words, reading “Married to a Legend” and learning what this man was like during courtship and marriage is a little like reading a tell-all by Martha Washington.

It’s also completely fresh information, a secret in plain view, because of the extremely limited attention given to Costa Rican first ladies in general – the third thing that sets Henrietta’s story apart. In the United States, our first ladies are legends in their own right. In a modern U.S. presidential campaign, the spouse and family are crucial. In Costa Rica, no one really cares.

Case in point: Just the other day, my family grabbed lunch and near the end of the meal, I noticed a woman paying the cashier, which tells you how fancy the place was. “Do you know who that is?” I asked my husband. He craned, looked, shrugged. “That’s your first lady.”

The partner of current President Luis Guillermo Solís, Mercedes Peña Domingo, walked unnoticed from the restaurant with their daughter, Inés, and stepped into an unmarked Casa Presidencial vehicle. I was going to write that she slipped unnoticed, but she didn’t have to slip, because no one there knew who she was, as the waitress and cashier confirmed to me.

So no wonder no one knows about Henrietta Boggs. My parents took our copy of her memoir back to Maine with them after their visit, so when I started working on this story, I went to several bookstores looking for another copy.

It was out of stock all over the country, both in Spanish and in English. I told one bookstore clerk I found this hard to believe, because I think it’s one hell of a yarn. I’m not the only person who thinks so.

As I watched him park the motorcycle and walk towards the porch, I felt slightly disappointed. He did not meet my college girl standards. He was not tall or handsome or even attractive in the usual sense of the word. He had a strange little half-moon smile that was almost impish and olive skin tanned by the sun… The only thing you noticed were his eyes, startlingly blue in that sunburned face.

-“Married to a Legend” (1992)

Filmmaker Andrea Kalin, who is the founder of Spark Media and director of that company’s upcoming documentary about Henrietta Boggs, “First Lady of the Revolution,” said she had the same reaction: How has this story never been told?

I contacted Kalin after seeing the trailer on Facebook, and we spoke by Skype in September. The award-winning director came across Henrietta by chance, too. She had produced several short-form documentaries for the Inter-American Development Bank, where Muni Figueres, one of Henrietta’s two children with don Pepe, headed up international relations.

Muni invited Kalin to a party at a Washington, D.C. home.

“When I came to her house there was this coterie of people surrounding someone — I couldn’t see who was in the middle. It was Henrietta, and she was telling stories,” Kalin recalled. “I was completely bamboozled.

“The next day I brought my camera and said, ‘I need to interview her, and I’ve gotta get this now.’ I didn’t know then that I would jump in full throttle and deep dive into telling her story.”

When work on the documentary began, Henrietta was 94. Kalin was astounded by the precision of her memories, her gifts as a storyteller, and her seemingly endless energy.

“I don’t even need a Foley library,” she said, laughing as she referred to the stock sound effects filmmakers use. “She’s making the clanks and the wheel sounds — you can visualize everything. [When she’s] on camera, sometimes I’m shaking my head. She’s not scripted, yet she’s so articulate. I have not seen her memory fault her.”

Kalin’s career has brought her into contact with an awful lot of extraordinary people. She’s documented the lives of medical pioneers (“Partners of the Heart,” 2003), trailblazing doctors from inner-city Newark (“The Pact,” 2006) and Syrian activists (“Red Lines,” 2014). Still, she says that Henrietta has had a unique influence on her.

“I’ve been making films for 20 years, but she is one of the most special individuals I have ever met,” Kalin said. “She’s living this life that makes you wonder what you’re doing with your own. She has a better social life than I do! She is a vibrant, dynamic, admirable person … she is who she is, and you either accept her or you don’t, but she’s fine either way.”

We nerded out, so to speak, chatting about different aspects of Henrietta’s story. Here are a few more nuts and bolts: Henrietta, eager to see the world and frustrated with the closed-mindedness and racism of her native Alabama, made that initial visit in 1940 to her aunt and uncle, who split their time between a home in Barrio Aranjuez and their small coffee farm, La Hortensia.

Figueres came to dinner one night to discuss coffee business and a courtship began. Following their marriage, he became increasingly frustrated with corruption in the government. He spoke out, resulting in his imprisonment and then the couple’s exile, which they spent traveling throughout Central America and Mexico.

Kalin marvelled at the key role her subject played in many of those moments, pointing out that Henrietta was the one who suggested Figueres choose the radio as the medium for his momentous speech criticizing the government. She was the catalyst for many key discussions during their time in exile, and his cover in Mexico as he collected the arms he’d need for the revolution (with her there, they could pass as a couple out for an outing at the location where Figueres needed to secretly arrange his purchases).

By all accounts, her constant advocacy for women’s rights, particularly voting rights, was hugely influential in Figueres’ own advocacy for those rights once he attained the presidency.

“I think they had a real intellectual synergy,” Kalin said. “They enjoyed talking about books, about philosophy, about Roosevelt, the New Deal. She was shocked when she came here to see the status of women in Costa Rica: It was very controversial and scandalous just to wear pants.

“She would talk to Pepe and say, ‘This can’t be. You can’t have development unless women are recognized.’ She feels that this did have an influence, but with the twist that’s Henrietta, she’ll say, ‘That didn’t change things at home. He was still the machista at home.’” (In the book, Henrietta recounts one incident in which don Pepe informs her, “I will fill this house with maids from the front to the back, but I will never change any child’s pants!” And he never did.)

One of the most remarkable things about “Married to a Legend” is the sudden end, both of the book and of the marriage. Henrietta describes a distance between her and her husband that grew throughout the Revolution and the founding of the Second Republic as Pepe’s attention to his family, which now included children Martí and Muni, came second to his political concerns, and his wife’s opinion appeared to matter little.

In her telling, things came to a head when a doctor’s concerns about possible uterine cancer results in a sudden hysterectomy. When Figueres made a ten-minute visit to his wife two days later, he brought with him two of his political collaborators so the three men could talk shop in her hospital room.

“Perhaps at that moment I decided to leave,” she writes, and a few months later, she did, her children at her side. Very few people aside from Figueres himself knew that the first lady and the first children were getting on that plane never to return — at least, not in that role.

Kalin said it is quite obvious that for Henrietta, discussing this drastic turn of events and the readjustment to life in the United States is still very difficult. (She went on to work with the Costa Rican delegation at the United Nations, to pursue her interest in writing, and eventually to found “Montgomery Living” magazine back home in Alabama.)

Kalin also said that one of the most interesting things about filming was watching the effect of the story on her Costa Rican crew members, particularly Paulo Soto, her associate producer and director of photography.

“In some of the earlier interviews, [Henrietta] talked about the war itself and the soldiers that were lost, and she said she knew the soldiers who were killed, and she got teary,” Kalin recounted. “Paulo was very moved, because he said, ‘My generation is not (connected).’ His generation is so cynical, but here, he could see how people persevered to establish something despite that.”

She gave me his email address.

Dazed and trembling I stood in the middle of the room, realizing that the 1948 Revolution had finally come home. I learned that when you were escaping, it was not so much what you took as what you left behind: the photograph of your mother in her wedding gown in the dented silver frame, the Bible you were given when you memorized the Presbyterian Shorter Catechism, your college Shakespeare with the passages marked in wavering lines of different colored ink, the harmonica you played in front of the fireplace in the family’s summer home in the Smokies.

-“Married to a Legend”

I met up with Soto for coffee one day in San Pedro, which, in “Married to a Legend,” was “a small town outside of San José” where the Figueres-Boggs family lived after the Revolution. Today, of course, its buildings and gridlock have melded completely with the capital.

Soto explained that he got connected with Kalin through the famed Costa Rican director Esteban Ramírez, who is a consulting producer on “First Lady” and with whom Soto has worked on various projects, serving most recently as the director of photography on “Presos” (2015).

Ramírez shared Kalin’s fascination with Henrietta’s story — Ramírez’s father, Victor, is Figueres’ biographer and was interviewed for “First Lady” — and put Soto in touch with the U.S. director.

Like Kalin, Soto spoke with awe of Henrietta’s seemingly boundless energy, talking of marathon days in San José during which crew members 60 years younger had trouble keeping up.

“I hope I’ll be as energetic as she is, but I probably won’t reach 97, let’s be honest,” he said with a smile. “What shocked me most is that she’s just so kind and polite. We were filming at the Club Unión [in downtown San José] and she was drinking water. ‘Are you ok, Paulo? Do you want a sip? Can I get you something?’”

Quickly, the conversation turned to the effects of hearing first-hand about the civil war.

“These people risked their lives. They were so fed up that they knew they might be killed, and they didn’t care,” he said. “You wonder, how can they not teach you about this more passionately in high school? What happened in 1948 — there has never been another revolution quite like it in the world.”

In his view, revisiting the story of Figueres is a bit frustrating as well, because it shows what’s missing from Costa Rica today.

“If you put a toad in a glass of water and you heat it little by little, he won’t realize it, and he just cooks,” he said. “For the past 30 years or so, the politicans have been screwing us, and the state has become so bloated.

“In 1948, the people were cast into boiling water, so they just snapped. We are non-confrontational and a very deferential people. We have lived off [don Pepe’s] legacy for so many years. I think we’ve come to a point where again the system is broken and the people are broken. It’s happened poquito a poco.”

I asked Soto, as I had asked Kalin before him, if Henrietta seems to feel a similar disheartenment or frustration. It was something I’d wondered, watching footage from the film of her looking out a car window as she speeds through San José. Her unusual former role within the country aside, wouldn’t it be depressing simply to see parking lots where a lovely hillside once was, or traffic, or evidence of crime?

Both filmmakers came back with a resounding “no.”

“She thinks very highly of this country; she is very optimistic,” Soto said. Kalin agreed: “Her love for the country runs very, very deep. She says how remarkable the infrastructure is … she does worry sometimes about what’s happening in terms of the focus on education, and the communal spirit that she felt she was a part of establishing in those early idealistic days and years, and the corruption.

“But those are also, as she explained, growing pains of a democracy. It’s a young democracy and a resilient one. From her perspective, as long as the values that built a society continue, it will not be forgotten.”

Soto seemed slightly less convinced, but said he believes that this particular film has a part to play in reminding Costa Ricans of an important chapter from their past.

“There is a way forward, and each one of us matters. This film could play a big role, showing us that there are things we can do. And at the very least, inspire a greater appreciation for what we have. … It has the potential to pluck a different string in people’s hearts.”

As had happened to me so often during the six years since I had come to Costa Rica, I asked myself once again what I was doing here. Here on a trail stumbling through the mountains about to be shot while my husband hid away in a distant valley at the head of a rag-tag bunch of crazy young revolutionaries, shooting grandfather’s old hunting rifles and trying to topple a corrupt regime dominated by crooks and communists… [But] if we survived, Costa Rica was where I wanted to be.

-“Married to a Legend”

“It’s such an extraordinary story,” I said, quite unoriginally.

“You know, I made the whole thing up,” deadpanned doña Henrietta without missing a beat.

It took me a while to track down the former first lady herself, which I did with Kalin’s help. At one point, Kalin contacted me saying that she had even gotten a bit concerned at the lack of response — only to discover that Henrietta had been at a dude ranch. Of course. Where else?

At another point, our interview was delayed because she headed off to Mexico for a book reading. In the interim, the news broke that she would deliver a talk at TEDx Pura Vida here in San José on March 3, in Spanish, to an audience of approximately 1,600, followed by a special screening of Kalin’s film for students of the Universidad Latina in San Pedro and Heredia to mark International Women’s Day. (The screening will also launch a competition in which students can vie to design the PR for the film and study design in Milán; the film’s general release is slated for October.)

I started to wonder if this story should focus, not on her life and times, but on her diet and exercise tips.

The only inkling I ever received of her age was when, in one email, she warned me not to plan an interview “longer than ‘Don Quixote’” because she would “run out of steam.” I promised to make it snappy.

One fine morning I finally called her on Skype, and that voice I had now heard several times was once more emanating from my computer. I asked, among other things, how she had remembered so many details when she wrote the book — it’s quite astonishing. She even recreates things people said in Spanish during her early days, before she spoke the language.

“I live with the horror of maybe boring people to death,” she said. “I’ve long believed that one of the characteristics of being charming is not to talk about yourself. In any case, I recreated a world which has now completely disappeared … and to recreate that, to large extent from memory, was challenging.

“I did keep a journal, but unfortunately it was left in Costa Rica [when she returned to the U.S.]. On the other hand, it was the first foreign country I had visited. Everything made a profound, deep impression on me.”

I told her that Paulo Soto and I had talked quite a bit about what Costa Ricans might take away from her story. What did she think our fellow U.S. citizens might learn from the Costa Rican example? She ticked off several things: from the importance Costa Rica has assigned to public education, contrasted with the U.S. public schools that are “slowly being gnawed away and underfunded,” to the fact that Costa Rica shows it is possible “to escape from the violence which seems to me to be a part of American society.”

Mostly, however, she talked about the Costa Rican character, casting a different light on the deference and conciliatory nature Soto and I had discussed.

“One of the strongest characteristics of Costa Rica is that citizens treat each other in a kind of soft, gentle, considerate way, and very rarely become violent, almost never,” she says. “That characteristic is still evident today in the way people treat each other, their political approach to problems, and their general attitude.

“That characteristic would benefit the United States, where we are living in such a divided community, not just politically but even to a certain extent in many social situations and even in religious communities. We choose the news source that confirms our already-held ideas and concepts, [closing] our minds against anything else.”

She talked about what it’s like to come back to a country that is so profoundly changed.

“I find very little evidence of the world we lived in then,” she said. “Among other things … in the days when I first lived there, the English speakers were really in control to a surprising extent of much of the life, certainly of the economic life. The international markets were in Europe and the United States.

“Now, Costa Rica has become a symbol throughout the world of a country that has transformed itself into one of the leaders of environmental protections, [addressing] climate change, all of that. Today it is right there leading the band.”

She mentioned the terrifying prospect of the drug war raging throughout Central America, expressing hope that Costa Rica will continue to maintain its grip on peace. Then she paused.

“What do you think?” she asked. “Do you think Costa Rica can do it?”

I thought about this. Just before calling her, I had read about a brutal assault in a sleepy beach town I dearly love, which contributed to my recent glumness about the country’s security. It is getting suffocating, the daily hammering of bad news. Sometimes it seems that a net is tightening around this country and there is no way out.

“I hope it can,” I said tentatively. “I mean — I think it can. I really do. I guess I think it can because I can’t accept the alternative.”

“Yes,” she said. “The alternative is too terrible to contemplate.”

I felt somehow part of a kinship as we chatted a bit further, two U.S. ladies pondering the future of a country we both love. Later, I realized I’d witnessed natural skill as a diplomat. Within just a few minutes over Skype, she had set me completely at ease, given me a voice, put serious issues on the table but also somehow renewed my flagging optimism and revved up my desire to get behind a solution.

In other words: she’s a first lady.

I lay there in my hospital bed and knew that my days in Costa Rica were numbered. And the knowledge broke my heart. Since my early twenties I had lived in Costa Rica and almost the only friends I had were there. Moving somewhere else meant ripping my life apart… It meant… trying to find solace for inescapable loneliness and nourishment for the hungry heart.

-“Married to a Legend”

When I said goodbye to Paulo Soto on the day of our interview and went over to pay for our coffees, I pulled out a ₡10,000 note, plastered with the familiar face of Henrietta’s first husband. With some of the change from that bill, I hopped into a taxi and headed home, turning at one of the many schools around Costa Rica named for José Figueres Ferrer.

When I arrived, my 2-year-old daughter was waiting for me: a daughter born into a country without an army, where women can vote (and wear pants) whenever they like, where a woman has been president. Kalin told me that Henrietta listened to a speech by President Laura Chinchilla in Washington, D.C., sitting next to Costa Rica’s ambassador to the United States at that time: her daughter Muni. Now that’s a full circle.

As I unlocked my gate, some words read long ago floated into my mind. The Danish writer Isak Dinesen, contemplating her departure from Kenya, asked: “If I know a song of Africa, of the giraffe and the African new moon lying on her back … does Africa know a song of me? Will the air over the plain quiver with a color that I have had on, or the children invent a game in which my name is, or the full moon throw a shadow over the gravel of the drive that was like me, or will the eagles of the Ngong Hills look out for me?”

Her words are loaded with the colonial context in which they were written, but on a simpler level, she’s expressing a basic human wondering, perhaps particularly intense when we are living far from our roots. This country that is transforming my life — am I making any difference here? When I leave it, in life or in death, will there be any trace of me?

One of the preliminary scenes from “First Lady” that Kalin shared with me brought me to tears: it was of Henrietta, alone at her home in the United States, and her family in Costa Rica gathering to celebrate her birthday with her through a video call. You see her children and grandchildren and other relatives drifting through the door bit by bit, embracing and preparing food, eventually getting online to sing to Henrietta, who beams in front of her computer with a cake in front of her.

No one in the scene seems sad, least of all Henrietta, who looks delighted to see her family and also fairly content when the call ends and it’s time for a slice of cake (making sure, no doubt, that the members of the film crew tuck in as well).

Still, it got to me, perhaps because I was a few days away from congratulating my parents on their 50th anniversary, also over a screen. In another clip, Henrietta says there are two kinds of people: those who are content where they are, and those who say, “Let’s go and see what’s on the other side of the hill.” When we do that, of course, there is a cost.

But wistful contemplation of this fact, or of the mark one has left here or there, is probably not one of the many activities on Henrietta Boggs’ busy agenda. The secret is probably to worry about your impact on the world when you look forward, and, when you look back, focus on what you’ve been given. Focus on the song of Costa Rica you will always sing, no matter where you go or what you do.

“Henrietta is a study in contrasts,” Kalin said. “She’s a rebel, a revolutionary and very much a Southern lady. She also still really identifies herself as a Tica, too. When you stay with her, there are little things that surround her. The ceramics in her kitchen, the food that she prepares, the cookies that she eats that her daughter or grandchildren will bring from Costa Rica, the Spanish that trickles into everything she talks about. That period of her life, seven decades later, is still the pinnacle.”