Respecting community and indigenous rights to collective land tenure and forest management could help avert climate change — and save us billions of dollars, according to a new report from the Washington-based World Resources Institute (WRI).

The report is based on case studies of community territories in Asia, Africa and Latin America — including indigenous territories in the Brazilian Amazon and community forest concessions in Guatemala’s Mayan Biosphere Reserve. Researchers found that forests under the groups’ control and management are better preserved, emitting less carbon and storing more than forests where local communities have weak control.

In the Brazilian Amazon’s indigenous territories, which cover 13 percent of the country, the benefits from carbon capture and averted emissions amount to $161.7 billion over 20 years, according to the report. And in the Mayan Biosphere, the benefits amount to $605 million over 20 years.

These findings will bolster the demands voiced by 300 indigenous women from different countries across the region who meet Tuesday in Guatemala City in the run up to the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21), which will be held in Paris from November 30 to December 11. The women want recognition of their role as key agents in the fight against global warming. They also want greater access to technology and financial resources to further that role.

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People, praised the WRI report. “[It] is very significant in terms of establishing the links between human rights and forest protection and sustainable use. It’s sending a message to governments to link respect for the rights of indigenous people to their land and resources to the climate change mitigation activities that [governments] are supposed to commit to,” she told The Tico Times.

Tauli-Corpuz added that the region’s governments need to do more to ensure that community land titles are respected and that indigenous lands are not taken over by special economic interests, like mining and monoculture plantations, or even drug traffickers.

“In Honduras, for example, indigenous people have collective land titles but [outside] land owners are invading their land for African palm plantations and there is invasion from other interests such as hydroelectric dams and mining,” she said.

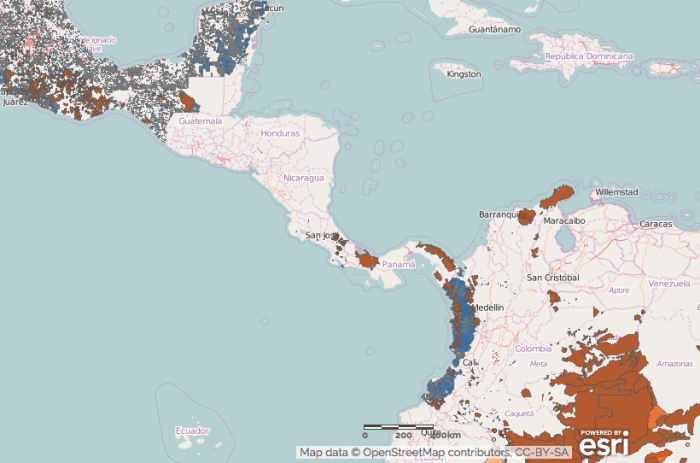

An interactive map released in conjunction with the report allows users to explore indigenous and community-owned land around the world:

Benefits of community forest tenure outweigh costs

The World Resources Institute study also found that the estimated annual cost per hectare of securing community forest tenure is low compared to the benefits from reducing carbon emissions and preventing deforestation. In Brazil, a $19 per hectare investment today would yield the equivalent of $1,473 per hectare in benefits in 20 years, WRI found. In Guatemala, a $63 per hectare investment today, would yield $1,899 per hectare in benefits, including economic benefits to communities through sustainable harvesting and the sale of forest products.

Peter Viet, director of the WRI’s Land and Resources Rights Initiative, said compared to the indigenous communities in Brazil’s Amazon, communities in Guatemala’s Mayan Biosphere Reserve found it harder to comply with the government’s long list of requirements for managing the land, which includes annual audits and forest management plans. “These communities are not indigenous; they were more recent groupings of individuals so they didn’t have the social cohesion and there were conflicts internally. Also, compared to Brazil, Guatemala is more bureaucratic and as a result, there’s more costs,” he said.

Overall, the figures presented in the report make a compelling case for the environmental, social and economic benefits of community forestry.

“In these two case studies we found that community forestry adds the highest value; it’s not agriculture or cattle raising or the exploitation of minerals, it’s sustainable forestry,” Juan Carlos Altamirano, an economist for the WRI, told The Tico Times.

Plus, community forestry can help reduce costs associated with resource conflicts that often accompany extractive industries, like mining, and others that are non-community based.

A recent study by Guatemala’s Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office highlighted mining and hydroelectric dams as the main source of conflict in Guatemala.

Community managed forests in Totonicapán

In the department of Totonicapán, located in Guatemala’s western highlands, forest land is divided into 48 cantons that have been communally owned by Maya Kiché communities since colonial times.

Logging within a three-mile radius of water resources is strictly forbidden and if a family needs to fell a tree for firewood, it must seek prior consent from indigenous community leaders and only the oldest trees can be felled. The penalties for breaking these rules depends on the size of the tree that was felled and range from planting five trees to paying fines equivalent to $64 to $102.

In order to ensure forest regeneration, every year in May leaders distribute tree seedlings from a community greenhouse so that every member of the community can plant five trees in an area of their choice.

The communities also observe strict rules regarding the use of water from six sources in the forest. If a family wishes to build a house it must seek permission from the local water committee. Using water for activities considered superfluous, such as washing cars and motorbikes, is forbidden.

According to Guatemala’s Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources, Totonicapán has the lowest deforestation rate in the country.

“The crucial factor in Totonicapán is communal land ownership and the establishment of strategic alliances with the government,” said Andrea Ixchiú, former president of the board of natural resources for Totonicapán’s 48 cantons. “Governance and the use of resources improves when communities coordinate actions with the state.”

If the benefits of community forestry outweigh those of environmentally hazardous industries such as oil extraction, why have the region’s governments been reluctant to phase out bureaucratic hurdles, implement agrarian reforms and invest in communal land ownership programs? According to the WRI, in 2013 indigenous peoples and communities held legal rights to only about 15.5 percent of the world’s forests.

Viet from WRI indicated that many governments are reluctant to cede control over natural resources to local groups because they don’t trust their ability to manage them well.

“There’s a real nervousness on the part of governments to decentralize forests to communities due to a concern over capacity,” Viet from WRI said. “Over time, when governments gain more confidence and the community shows it has the capacity, it could lift some of those conditions.”