Want to help stop illegal fishing around Costa Rica’s remote, species-rich Cocos Island? Now you can, from the comfort of your couch anywhere in the world – as long as you have a fast Internet connection.

The ocean conservation group Turtle Island Restoration Network has teamed up with the imagery crowdsourcing platform Tomnod to launch a campaign that allows conservation-minded Internauts to identify illegal fishing boats in satellite imagery of Cocos Island National Park. Turtle Island hopes the initiative will produce evidence that could eventually be used in court to prosecute people fishing illegally within the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

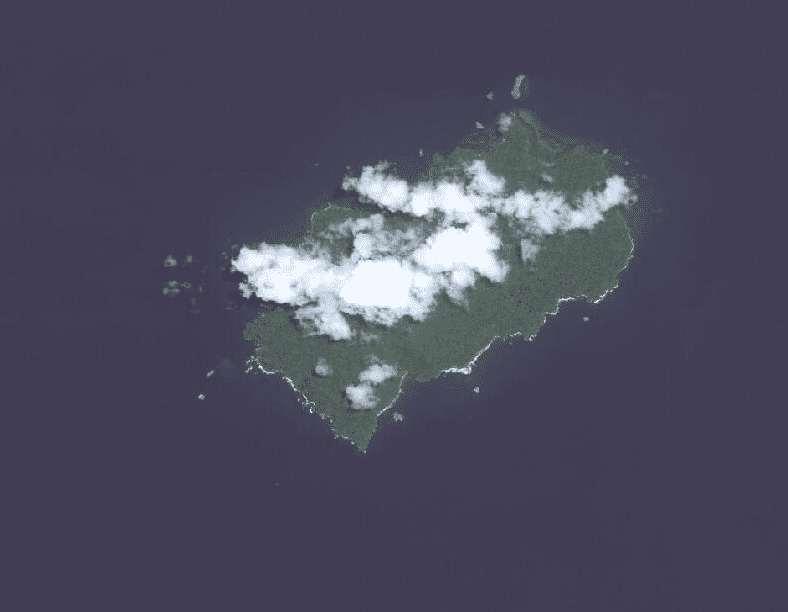

Armchair patrollers can go to Tomnod.com and scan for illegal boats in five satellite images covering a total of 3,200 square kilometers of ocean around the island. The images are broken down into tiles and the user can zoom in and out (the default size is one-eighth of a square kilometer). If a user spots what looks like a boat, she can tag it with a digital pin and the data is automatically saved.

Tomnod collects all that data and shares it with conservationists.

“This is likely the first time this sort of crowdsourcing technology is being used to protect a marine reserve,” Turtle Island spokeswoman Joanna Nasar said. As such, it’s in beta phase.

Scrolling through images of the vast expanse of slate blue Pacific ocean streaked with whitecaps – and occasionally covered with wispy clouds – can be overwhelming. But it’s also mesmerizing.

Tomnod has previously used its satellite imagery crowdsourcing platform to help rescue workers locate crumbled buildings and tent camps in Nepal and help conservationists identify illegal poaching camps in Africa.

In the first two days of the Cocos Island campaign last week, more than 5,700 people from 115 countries searched through the satellite imagery, according to Tomnod’s crowdsourcing manager Caitlyn Milton.

Currently, most of the images from Cocos Island on Tomnod are a year to a year and a half old, Milton said. But Tomnod, which is owned by satellite company DigitalGlobe, has asked its parent company to collect new images of the park, she said.

Turtle Island’s Nasar is excited about the potential.

“This is a first pilot program, a trial run to see what we get,” she said. “Turtle Island is ready to use any and all technology to help protect this reserve.”

The bountiful waters around Cocos Island are a strong attraction for illicit fishing outfits, which take advantage of minimal policing to troll for popular eating fish, like tuna and shark. Many use longlines dragging hundreds or even thousands of hooks that often ensnare endangered sea turtles, sharks and cetaceans.

Fishing is illegal within a 12-nautical-mile marine protected zone around the island.

Recommended: Shark fin scandal in Costa Rica has Solís administration on the defensive

Conservationists have launched several initiatives this year aimed at improving policing around the island, which is complicated by the island’s remoteness and a lack of funding for patrols. In April, conservation groups launched a fundraising campaign to buy a speedboat for Cocos Island park rangers.

And in May, Turtle Island Restoration Network, through its local branch, Protoma, and the National System of Conservation Areas began testing drones as a tool to spot illegal fishing boats around the island.

Nasar says the imagery crowdsourcing initiative is one more tool conservationists can add to their box.

“We can pair [satellite images] with radar from the park … and we can get a big picture overview of the island in a way we haven’t had before.”

Plus, involving ordinary citizens in conservation efforts at the island helps raise awareness about the challenges and importance of preserving this biological jewel, Nasar said.

“It’s also exciting because not everyone is going to be able to visit Cocos Island, and this allows everyone a chance to get involved.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the Cocos Island campaign was Tomnod’s first imagery crowdsourcing campaign over water. In fact, Tomnod allowed users to search the ocean for missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 when it disappeared last year.