MONTERREY, Mexico — The attack that burned 52 people to death at a casino in an upscale neighborhood was bad. But what really scared Idalia Villafana’s customers away were the body parts once strewn across the plaza near her restaurant.

Villafana, 41, says she still can’t believe that the barbarism wrought by the Zetas drug cartel has largely subsided here near Monterrey, Mexico’s third-biggest metropolis, just a few years after she’d almost given up hope for peace.

For that, she can thank local business leaders who got fed up with the penetration of the legal system by criminal syndicates and helped create and fund a unique program to take back the streets. The result: Murders in this industrial hub on the steps of the Sierra Madre are at a five-year low and commerce is once again thriving.

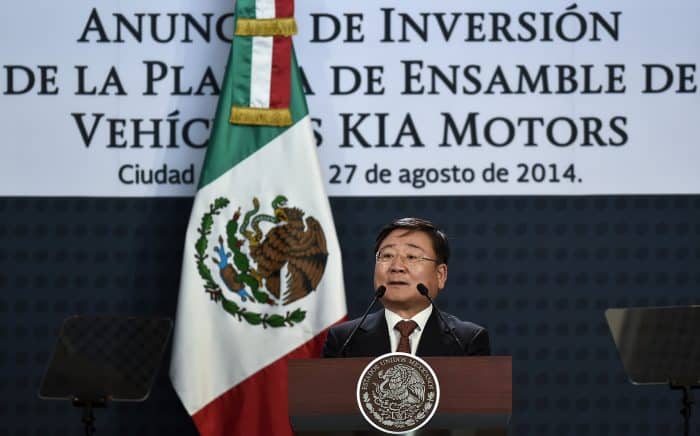

A bustling symbol of the turnaround is the factory South Korea’s Kia Motors is building for more than $1 billion not far from where the Zetas once operated a paramilitary base. That’s helped push the wider Nuevo León region, which touches Texas, past Mexico City as the national leader in pledged foreign direct investment, with another $6 billion expected this year, state officials say.

The money is trickling down the way it should for small-business owners like Villafana, who has a contract to feed 190 of the workers from the Kia project at her modest, white-washed eatery. Villafana says she struggled to pay a single employee at the height of the violence in 2011, when the casino attack occurred. Now she has six and is struggling to keep up with demand.

“We thought this would become a ghost town if things stayed the same,” Villafana says as she dips a ladle into a steaming pot of zucchini, her fingernails painted light blue. “Instead, there’s lots of work. The plant has really helped.”

Mexico has been wracked by drug-related violence that’s left more than 22,000 people missing and 70,000 dead in the past eight years, including 49 headless corpses dumped en masse on the highway linking Monterrey to the United States. While the murder rate has begun to fall, President Enrique Peña Nieto has faced criticism for surges of violence in some regions, such as the abduction of 43 students in western Mexico last year by corrupt cops who allegedly handed them over to a drug gang to be killed.

Monterrey, the hub of a metropolitan region of 4.2 million people, is a linchpin of Mexico’s economy, with output per capita of about $20,000 a year almost double the national average.

The city’s transformation would never have been possible without wholesale changes to the law-enforcement system, which was widely seen as infested with drug money, according to Guillermo Dillón, who runs the state’s industrial chamber, a lobby group whose members include cement maker Cemex SAB and the Alfa SAB conglomerate.

The tipping point came in 2008, when kidnappings reached epidemic proportions, prompting the chamber to organize a media event to urge officials to act, Dillón said in an interview.

“We said we were receiving very troubling complaints from many members who were threatened by kidnappers,” Dillón said.

That event helped galvanize the public and embolden other business leaders to join the charge for change, including the late Lorenzo Zambrano of Cemex and Fomento Economico Mexicano SAB’s José Antonio Fernández. As popular support for a thorough cleansing of the state police department swelled, a group of politicians, businessmen, educators and non-governmental organizations was assembled and tasked with an overriding objective: build a brand new force.

Businesses contributed about 50 specialists in public relations and human resources to create recruitment campaigns to attract the ideal officer — anyone who’s never been a cop. They set pay and benefits that far outstrip those in other states, such as private health insurance and scholarships for kids. Professors were brought in to help write the training manuals for the new police academy. They ran market studies to design a name and uniforms that inspire trust.

Thus, Fuerza Civil, or Civil Force, was born.

“It was important to have this collaboration between the private and public sectors,” Javier Trevino, a deputy education minister who was lieutenant governor of Nuevo León from 2009 to 2012, said by phone from Mexico City. “It was a good way to earn the trust of the community.”

Four years on, the state’s Fuerza Civil is more than 4,000 members strong and 70 percent of Monterrey’s municipal cops have been purged. An alliance of cartels that teamed up to repel the Zetas in the state may also have helped reduce violence, according to political scientist Javier Oliva at Mexico’s National Autonomous University.

The drop in crime — homicides have plunged 76 percent and car thefts 86 percent — has been so steep that violence is no longer the public’s single greatest concern, according to Pedro Torres, a security and law analyst at the Tecnologico de Monterrey university’s school of government.

The success of Nuevo León’s security revamp may serve as a blueprint for other states such as Jalisco, home of the country’s second-largest metropolis, Guadalajara. There, cartel gunmen recently shot down a military helicopter and erected roadblocks from burning buses and debris amid clashes with police that left at least seven people dead.

As voters in Nuevo León prepare to elect a new governor next month, a rare independent candidate in a region with an entrenched two-party system, Jaime Rodríguez, is polling second. “El Bronco,” as he is known, survived two assassination attempts during the height of the violence, when he was mayor of a Monterrey suburb, and is now pledging to root out old- fashioned cronyism and graft.

“Security isn’t my priority anymore,” said Osmar Dávila, a 19-year-old criminology student with a vivid memory of the shootout between cops and gang members that erupted outside his house three years ago. “It’s cleaning up the government.”

With assistance from Thomas Black in Dallas.

© 2015, Bloomberg News