HAVANA, Cuba — Many of the Cuban diplomats negotiating detente with the United States — talks resume this week in Washington — are graduates of Cuba’s Advanced Institute for Foreign Relations. It’s the Castro government’s foreign service school, located in a drab, blockish building along Calzada street in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood.

Less widely known is that the building was originally constructed as the Instituto Cultural Cubano-Norteamericano (U.S.-Cuba Cultural Institute), and was once a mainstay of the two countries’ deep and complicated ties.

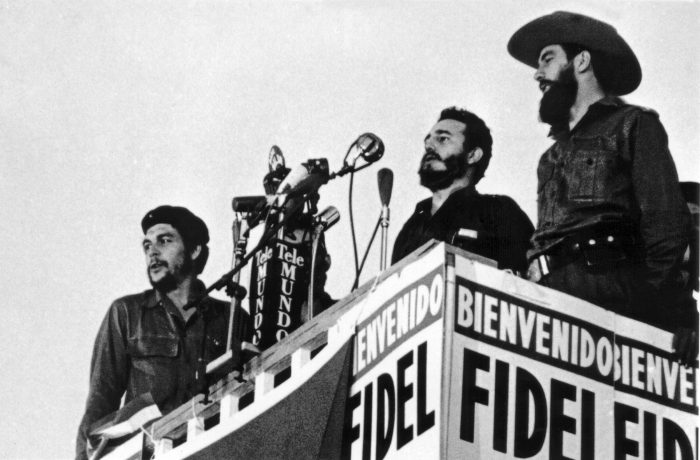

Like many buildings whose pre-1959 use didn’t fit with Fidel Castro’s post-revolution plans, it was taken over and repurposed soon after the rebel convoys rolled into Havana. The institute’s days as a center for U.S. cultural promotion came to an abrupt end, and its long-time director, historian Herminio Portell Vila, fled for Miami.

With the United States and Cuba now moving toward restoring long-broken relations, it’s not hard to imagine such an institution returning again at some point — though not likely at its former location.

Inaugurated in 1943 at the height of World War II, the institute began with 200 students, offering courses in English and U.S. history. Its Martí-Lincoln Public Library, named for Cuba’s national hero and the venerated U.S. president, was one of the first in Havana to allow users to check out and borrow books in the style of a U.S. public library, according to Cuban journalist Waldo Fernández Cuenca.

Fernández recounts this history in the December issue of Palabra Nueva, the magazine of the Havana archdiocese, and said the library’s entrance featured a painting by the prominent Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros (who, ironically, was a militant Stalinist).

“I wanted to rescue this forgotten history,” Fernández said. “It was an example of the close ties and cooperation between the two countries.”

The library’s shelves soon filled with donated books from the U.S. government and well-heeled U.S. supporters, many of them prominent investors in Cuba. Library visitors had access to all the current editions of Time, Life, Vogue and the like.

‘Employment of Cuban civilian personnel’

As an extension of U.S. culture, it was also at times an extension of the United States government. This 1945 State Department cable shows that U.S. military officials tasked Portell Vila with providing a report on the Cuban educational system, with the goal of hiring Cuban civilians for U.S. military bases in Cuba.

When the United States closed its base at San Antonio de los Baños at the end of World War II, the secretary of the War Department transferred more than 4,000 volumes to the Institute’s Martí-Lincoln library, according to Fernández. The library was well-known for its collection of military history, especially its World War II materials.

Cubans seeking scholarships to study in the United States flocked to the institute. By the late 1940s, it processed more than 800 applications a year from Cubans wanting to study aviation, meteorology and other courses at U.S. schools.

With its popularity growing, the institute moved in 1950 from its original location along Old Havana’s Prado Boulevard to a new site in Vedado, erecting a six-story edifice with 23 classrooms, a huge library and capacity for thousands of students.

Then-Vice President Richard Nixon visited the institute during a trip to Havana in 1955, calling it “a vital element in the U.S.-Cuba relationship that grows closer every day” in a letter to Portell Vila.

With Castro’s rise to power and a rapid deterioration of U.S.-Cuba relations, the institute came under a cloud of suspicion. An article appearing last year in the communist party daily Granma made rare mention of the institute’s existence, describing it as beachhead for U.S. espionage and “an institution dedicated to influencing and penetrating Cuba’s scientific, academic and cultural sectors.”

After taking control of the building and its well-appointed library collection, the new Castro government kept the school’s original function as a language academy, though English-speaking instructors were replaced by Russian and German ones. The old name lived on, according to Cubans who studied there and knew it as the “Lincoln school” well into the 1970s.

When the language academy shut down in the 1990s, the building was used as Education Ministry offices, then became the new training academy for Cuba’s Foreign Ministry, located just two blocks away.

Today it is not among the storied Havana landmarks associated with pre-Castro Cuba and the ill-fated era of U.S.-Cuba intimacy, like the iconic Hotel Nacional or the Cuban Capitolio. But Fernández, who dug up much of the U.S.-Cuba Cultural Institute history using copies of its old newsletter, “Dos Pueblos,” said it’s a legacy worth revisiting.

“In the end, I think its contributions to Cuba were more positive than prejudicial,” he said. “It didn’t even last two decades, unfortunately, but maybe some day something like it will emerge again.”

Miroff is a Latin America correspondent for The Post, roaming from the U.S.-Mexico borderlands to South America’s southern cone. He has been a staff writer since 2006.

© 2015, The Washington Post