In downtown San José, just west of the Cementerio de Obreros, sits a forgettable lot of urban real estate where the municipality and the Public Works and Transport Ministry park garbage trucks and heavy equipment. But on this same spot 73 years ago, an internment camp was erected by the government to hold hundreds of German-Costa Rican prisoners after the United States and Costa Rica entered World War II in December 1941.

Costa Rica’s popular image today as an environmentally friendly, neutral country without an army hardly meshes with the idea of Tico troops rounding up people into camps. But at the behest of the U.S. State Department, that is exactly what happened following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Concerned about a so-called fifth column — a group of Axis nationalities conspiring against the U.S. and Allied war effort — the State Department leaned heavily on Latin American and Caribbean governments to expropriate property from Axis nationals and either imprison or deport them to the United States or Germany through a Special War Problems Division. The little-known division was responsible for amassing a blacklist of Germans and Italians in Costa Rica, along with orchestrating the policy of internment across Latin America, the Caribbean and the U.S.

There are few people still alive who remember these events firsthand, but to mark the 73rd anniversary of the Pearl Habor bombing this month, The Tico Times spoke with several who either experienced them or whose families were impacted by them.

“Before, it was perfectly fine, people were even proud to have German friends. But the war changed many things – not for everyone – but when the order came from [U.S.] President Roosevelt to round up Germans across Latin America, things changed,” said Hermann Kruse, 85. Kruse was a boy when the war broke out and his father was interned in the San José camp.

La Tribuna, a Costa Rican newspaper, captured the surreal situation in an article dated Dec. 11, 1941 trumpeting the speedy construction of a “concentration camp” to be built in San José and designed to hold 400 men of German, Italian or Japanese descent. The newspaper’s description of the project reads like a perverse hotel review, including “very accommodating” dormitories, kitchens, dining halls and a visiting area all encircled by three rings of electrified fences. “What we want is that the concentration camp offer all the biggest and best accommodations,” said then Public Security Secretary Francisco Calderón, according to La Tribuna.

Kruse recalled visiting his father in the camp’s visiting area: “There was a long display with chairs lined up for waiting, and the prisoner would show up at a certain time to talk for 15 or 20 minutes until the guard said enough.”

Kruse’s father became a Costa Rica citizen in 1933, but that was not enough to keep him out of the camp. Some of his male relatives were also held at the camp, but the same could not be said for Kruse’s uncles, including one who served in the German consul in Puntarenas. They were among 379 German-Costa Ricans deported to the United States, where they were sent to detention centers in Texas and other states alongside Japanese internees.

Along with the imprisonment or deportation of German families, the Costa Rican government expropriated property from many elite German families who dominated coffee, sugar and other export industries. Germans had been moving to the isthmus since the 19th century in search of opportunity in the Americas and found fertile ground in the coffee business in particular. By World War I, Germans were well established in many key export industries in Costa Rica, from coffee, bananas and cocoa to electrical generation and the importation of finished goods from Europe. But economic success had blinded many of Costa Rica’s German population as to what the war in Europe would bring.

With a naval blockade separating Costa Rica from its European markets, a deal was struck for the U.S. to buy its coffee with a catch. The State Department announced that it would boycott all exports from German-owned businesses, most notably coffee. Coffee constituted more than 54 percent of Costa Rica’s exports between 1938 and 1945 of which Germany purchased roughly 40 percent, according to economic historian Gertrud Peters of Costa Rica’s National University. As a small country dependent on exports, Costa Rica had little choice but to agree to U.S. demands.

The expropriations might have been obligatory but they have also been criticized by scholars as opportunistic. The Victoria sugar factory owned by the Niehaus family was expropriated in March 1943 at an estimated value of more than $700,000 in today’s dollars. The sugar factory became the first agro-industrial cooperative in Costa Rica later that year, according to research by historian Carlos Meissner. Expropriated property was also leveraged to pay down the country’s soaring national debt.

“The government of President Rafael Calderón Guardia took advantage of a lot of things,” Kruse said. “When they would take away the Germans, a group of men, I don’t know if they were police or what, would show up with boxes and take away everything in the house supposedly to guard it until they came back,” he added.

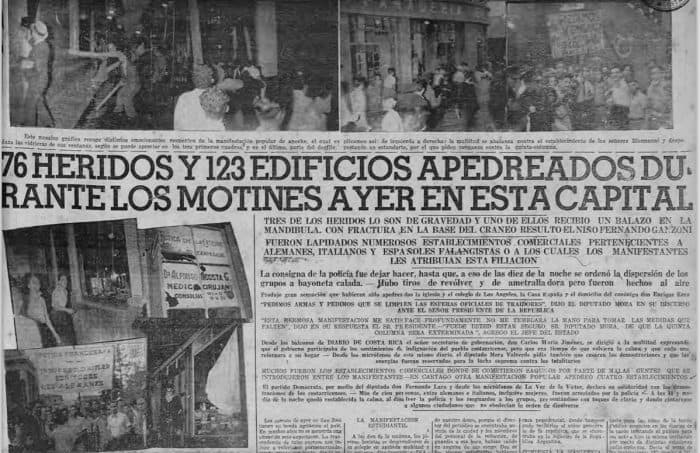

Costa Rican-German relations reached their nadir when riots broke out in San José on July 4, 1942, following the torpedoing of the San Pablo, a United Fruit Company ship docked at the Caribbean port of Limón. Twenty-four Costa Ricans were killed in the German U-boat attack. More than 120 shops of German-owned businesses were looted, 76 were injured and 15 tons of glass were broken. Reportedly, 100 German and Italian residents were arrested followed the unrest.

The newspaper Diario de Costa Rica reported on July 5, 1942 that looters had infiltrated the demonstrations and that pistols and machine gun fire was heard. Kruse recalled seeing a man throw a bicycle through the window of a German-owned camera shop as looters grabbed everything they could carry, leaving the shelves empty. President Calderón Guardia (1940-1944) was quoted as saying the demonstrations “greatly pleased him” and that the “fifth column would be exterminated.”

As the war ended in 1945, the camp was closed and detainees returned to their families, homes and businesses, if they were able to keep them. Some reclaimed lost property, but others could not and faced starting over from nothing.

“Those who had properties here tried to transfer them into the name of others before they left. Sometimes, after they returned, they tried to reclaim their property, and people would say, ‘What farm? I have a document here that says you sold it to me.’ That was a shame,” Kruse said.

Just a few years after the end of World War II, Costa Rica entered into civil war, and José Figueres Ferrer rose to the presidency. After a short-lived coup d’état, Figueres abolished the armed forces in 1948 and codified the move in the 1949 Constitution.

Kruse did remember another story of a Costa Rican family who cared for a German family’s farm. When the Tico approached the German to return the farm to his name, the German rewrote the contract so that they were 50-50 partners.

Said Kruse: “There were injustices committed by Costa Ricans and others by Germans here during the war, but there was perfect harmony between others.”