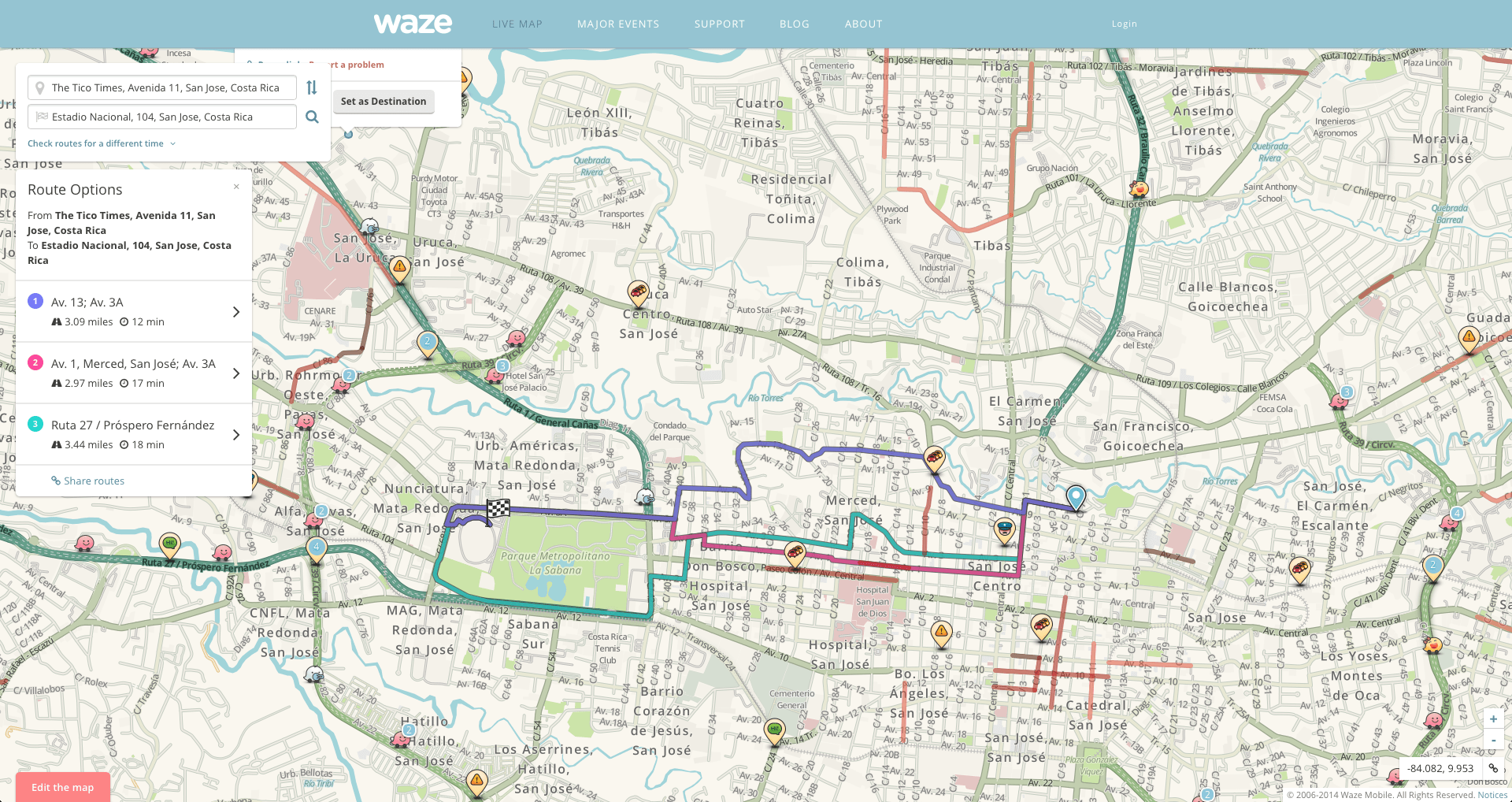

See also: Waze partners with San José to improve city traffic

“It’s a nightmare.”

That’s how Eduardo Carvajal describes the Costa Rican way to give an address.

“If I want to give the address of my office I say ‘Okay, go to the ice cream cone shop in Curridabat then drive 100 meters south and 50 meters east,” Carvajal said.

He’s part of the team of volunteers who mapped Costa Rica in Waze, a crowdsourced traffic and navigation app. Carvajal, whose day job is running a software company, has made hundreds of thousands of edits to Waze’s map of Costa Rica.

Fellow volunteer Felipe Hidalgo spent 50 hours a week for almost two years helping to map the country. Hidalgo has made 378,000 edits to maps in Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Cameroon, St. Helena Island, Panama and Trinidad and Tobago. He described the work as addicting. Since the mapping of Costa Rica was completed, he scaled back to 10-15 hours a week.

“I was crazy about it, and my wife was so mad with me, I used to go to the bed and take the computer with me,” Hidalgo recalled.

Carvajal and Hidalgo weren’t paid for the hours they’ve spent annotating and labeling roads and landmarks on satellite images of Costa Rica, or vetting the edits other Waze users have made. But the duo, and other Waze power users who were interviewed for this story, describe it as fun and rewarding work.

“Some people ask ‘Why do you work for free? Why do you spend so many hours a week doing this mapping?’ ” Hidalgo said. “You feel good about knowing that the people who drive around every day save time because you are investing your time in fixing the roads and doing this mapping.”

“We don’t receive any money, but for us, everybody in Costa Rica uses Waze — believe me — for me it’s more important than all the money on the Earth,” Carvajal said.

The country was mapped completely by volunteers who wanted to make it easier for their countrymen to get from point A to B. The app is especially popular in the capital, San José, boasting 300,000 active users. On one day earlier this month — Oct. 17 — users reported nearly 47,000 incidents, which include things such as a traffic jam, an accident or hazard.

“It’s one of the top five markets in terms of absolute numbers, and that’s even though we have like 4.5 million people,” said Sebastián Urbina, Costa Rica’s vice minister of transportation.

Waze, which began as an Israeli start-up, was purchased by Google last year.

Waze became the dominant mapping system because it’s free to use, and was superior to alternatives, such as Google Maps and GPS, which lacked real-time data and the level of detail that Waze came to have.

The app is especially popular because of the unique challenges of navigating Costa Rica.

“Most of our streets don’t have road names so a lot of the addresses end up being very much next to some kind of landmark associated with it, and that’s how we give directions,” Urbina said. “There’s never been good maps generated to be able to get to where you’re trying to go.”

Waze has become such a part of the culture that businesses will even list their addresses in advertisements as locations that can be searched for on Waze.

If inviting friends over for a party, it’s common to share a Waze hyperlink to one’s address through a WhatsApp group or a Facebook event.

That way a driver doesn’t have to know every landmark in the country, a feat that’s especially challenging for young people and tourists.

Costa Rica’s government recently partnered with Waze as part of its Connected Citizens campaign to share information with Waze on road closures. So if Urbina has to close a highway due to a storm, that information is automatically shared with Waze, and drivers using the app are all instantly aware.

“I’m trying to leapfrog the technological development that a lot of cities go through. More developed cities have invested significant amounts of money in traffic cameras and in road sensors. It’s very expensive and although we have some traffic cameras they’re very, very limited in the city,” Urbina said. “And I don’t have the money to build up as many as I would need to have proper management. So this level of connection, crowdsourcing and community-based collection allows me to leapfrog that whole development stage for the cities to be able to start, and be able to make the same type of decisions that other cities do without actually having to go through that level of investment.”

He also plans to use Waze to identify when the police department should send officers to direct traffic, and to measure how effective each officer is at improving traffic jams.

“We dispatch the police officer and then Waze is going to tell us, ‘Oh now traffic flow is better.’ So we link that improvement to that officer. And then we’re able to generate data associated with not just can we improve it by sending an officer, but how good is that officer at improving. So we rank the officers and decide where we send them,” Urbina said.

As positive an impact as Waze has had, the service has inadvertently empowered some dishonorable behaviors. One Costa Rican Waze user highlighted the usefulness of being able to share where police officers are located.

He explained how a driver who may have had one drink too many could know what streets to avoid. Or a driver who is violating San Jose’s tag days — where certain license plates aren’t allowed on streets on given days — can avoid a ticket by steering clear of certain intersections.

Watch a trippy data visualization video of a single day of San José traffic on Waze here.

© 2014, The Washington Post