FREETOWN, Sierra Leone — The dreaded Ebola virus came to the children’s hospital in the form of a 4-year-old boy.

His diagnosis became clear three days after he was admitted. The Ola During hospital — the nation’s only pediatric center — was forced to close its steel gates. Fear swelled. The boy died. The 30 doctors and nurses who had contact with him were placed in quarantine, forced to nervously wait out the 21 days it can take for the virus to emerge. And remaining staff so far have refused to return to work. They, along with millions of others, are facing the worst Ebola outbreak in history. Already, the hardest-hit West African nations of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone have reported more than 3,000 cases, including the infections of 240 health-care workers.

Ebola is now spreading from the remote provinces and into the teeming cities such as Freetown, where 1.2 million people jostle for space. Previous outbreaks had been limited to remote villages, where containment was aided by geography. The thought of Ebola taking hold in a major city such as Freetown or Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, is a virological nightmare. Last week, the World Health Organization warned that the number of cases could hit 20,000 in West Africa.

“We have never had this kind of experience with Ebola before,” David Nabarro, coordinator of the new U.N. Ebola effort, said as he toured Freetown last week. “When it gets into the cities, then it takes on another dimension.”

The hemorrhagic fever has no cure. Odds of survival stand at about 50-50. Detection is difficult because early symptoms are hard to distinguish from those of malaria or typhoid, common ailments during the rainy season. While Ebola is not transmitted through the air like the flu, it does spread by close contact with bodily fluids such as blood, saliva and sweat — even something as innocent as a tainted tear.

Now it is headed to Freetown, where the streets hum with low-level panic. People long ago stopped shaking hands. Hugs are unheard of. Plastic buckets filled with a diluted chlorine solution are posted outside many businesses to encourage hand-washing. Some of these homemade solutions tingle and burn; others smell like aromatic cleansers. For a while, street peddlers, who normally sell peanuts or umbrellas from stacks balanced on their hands, sold surgical gloves, $1 each.

But the roads are still crammed with autos and people, stray dogs and wild chickens. Trucks with loudspeakers rumble down rutted roads.”Wash your hands!” they announce in Krio. “Ebola is real!” shout banners strung throughout the city. Radio ads detail the virus’ symptoms: headache, fever, nausea and vomiting. The government of Sierra Leone has been running these messages in the capital for months, just in case.

Sierra Leone’s first case appeared in late May, in the distant Kailahun district. A month later, the country had 158 total cases. In late July, it was up to 533 cases. A national state of emergency was declared. Soldiers erected roadblocks to cordon off the rural epicenter, raising memories of the country’s brutal civil war, which ended in 2002. Residents were ordered to stay at home for one day of prayer and reflection. An evangelist texted tens of thousands of people before dawn one morning, telling them to douse themselves in saltwater for protection from Ebola. People rushed into the streets, singing and washing.

“It looked like panic,” said Killian Doherty, an Irish architect living in Freetown. “It’s the kind of thing that makes you lose your bearings.”

The government has passed laws to limit close contact, altering the city’s daily rhythms. Riders in the city’s many “Poda Poda” minibuses, usually packed shoulder to shoulder, are now curtailed to four people per row. “Okara” taxi motorbikes are restricted at night. Even banks have cut hours to limit time spent in their crowded lobbies. And large public gatherings have been outlawed. The small cinemas where patrons would pay to watch foreign soccer matches on TVs have been shuttered. The popular clubs along Freetown’s Atlantic Ocean beaches are now empty.

Recently, a group of 12 men sat on benches under palm trees along Lumley Beach. Technically, this was illegal. The men all knew about Ebola, even reciting how the virus got its name from a Congolese river near where the first outbreak was discovered in 1976. Still, they didn’t know what to think of this strange disease. This country, where doctors are few and over half the population lives in poverty, knows plenty about malaria and cholera and even Lassa fever, a more forgiving hemorrhagic fever spread by rats. But Ebola was new to Sierra Leone.

“I don’t believe 100 percent that Ebola is real,” said Moses Sensie, 32, who works in security for a construction company. The movies he has seen about the virus show victims bleeding out in the disease’s last stages. He hasn’t heard about that happening now, and experts acknowledge hemorrhages in this outbreak have been rare. “I believe in Ebola maybe 60 percent.”

But Anthony Jimmy, 30, was not taking chances. He times his commute to work on the Poda Podas so they are less crowded. He avoids people who look ill. But, he said, the worry was exhausting.

“People are fed up with the situation,” Jimmy said.

Many of the people who can afford to leave Freetown are gone — some on vacation, others to foreign countries to wait out the virus. But getting out has become harder as several airlines have stopped flying to Lungi International Airport. Air France, under orders from the French government, became the latest last week. The nation’s school year is supposed to begin Sept. 9, but few expect that date to hold.

At the Lighthouse Hotel, the usual executives from the mining, pharmaceutical and banking industries are absent. The hotel is running at 15 percent occupancy, said general manager Andrew Damoah. He is barely able to cover the cost of gas for the hotel’s generator — a necessity in a country with a shaky power grid. Most of his guests now are the international doctors and nurses responding to the outbreak.

“We are all running empty hotels,” Damoah said.

The city’s hospitals are empty, too. People avoid them over worries about catching Ebola. They would rather suffer at home and hope that what they have is just a mild case of malaria. It is not an unreasonable concern. The Kenema government hospital in the provinces has seen 40 staff members die of Ebola. At Connaught Hospital in Freetown, the doctor running the Ebola ward died two weeks ago. Shortly before that, the government issued a public alert for a 32-year-old hairdresser with an Ebola diagnosis who was pulled from Connaught by her family. They wanted her to be treated by a faith healer. All of them subsequently died of Ebola.

“Everyone is scared. Even I am scared,” said Michael Karoma, a gynecologist who heads Prince Christian Maternity Hospital in Freetown, where is he working to restore the confidence of his staff and the public. “Everyone is afraid of Ebola. This used to be in the villages. Now it is in the cities. What is happening in the world?”

Recommended: Costa Rica-based US relief workers join efforts in West Africa to combat ebola

Connaught Hospital, the city’s main health-care center, is in Freetown’s historic heart, not far from the massive cotton tree featured on Sierra Leone’s paper money. The hospital’s small Ebola isolation ward is part of the nation’s triage system. Patients suspected of having Ebola wait for lab results before being shipped to the country’s only two treatment centers, a facility in Kailahun run by the aid group Doctors Without Borders and the government hospital in Kenema.

At Connaught, the Ebola ward sits behind a gate with prison-like metal bars. Staff members are covered head to toe in protective scrubs. The unit recently had 12 beds for 13 patients. At first, one or two patients were being diagnosed with Ebola each day. That picked up to three a day. Now, lab results on up to seven people a day are coming back positive.

The virus’ march into Freetown was slow to start. The first case officially emerged in mid-July. Six weeks later, the city had 30. The number is now over 40 and is expected to quickly shoot up.

The Ebola ward at Connaught is now run by Marta Lado, a Spanish doctor who arrived in March. A high-level delegation of World Health Organization officials visited her last week. Nabarro, the United Nations’ new Ebola point man, wanted to know what she needed.

“If you could get anything,” he asked her, “what would it be?”

Lado stood in her sweat-stained blue scrubs and thought.

More people and supplies, she said. “The health-care workers are really scared. This is hard work. We can’t tell them we don’t have enough supplies — to just come to work and later on you’ll have gloves.”

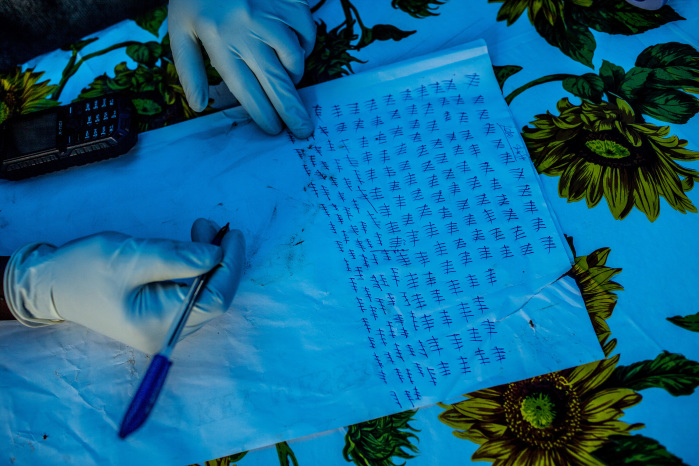

They go through 200 disposable gloves a day in the isolation room. They had enough for now, but the supply was running short.

This wasn’t a problem just at Connaught. Doctors Without Borders has warned about a worldwide shortage of the full-body protective suits worn by Ebola health-care workers. Sierra Leone’s Ebola emergency operations center said it faces a six-week wait for the specialized ambulances needed to transport Ebola patients.

A new Ebola treatment center — the country’s third — is expected to be constructed near Freetown. But it might not be ready for a month. Just outside Freetown in Lakka, a new Ebola isolation unit is almost open, on property shared by a tuberculosis hospital and housing for sufferers of leprosy. A mobile Ebola testing lab, flown in from South Africa, also just started up.

Outside the Ebola facility in Lakka, a single Sierra Leonean soldier stood guard, rifle slung over his shoulder. Balla Conteh, 35, did not like his new posting. His younger sister is being treated for Ebola in Kailahun. His 4-month-old niece died of the disease.

“It is real. It is very real. And it is killing people,” Conteh said. “It’s a very, very scary disease.”

That fear might explain how the young boy suffering from Ebola was admitted to Ola During Children’s Hospital.

The boy showed up at the hospital with his father, doctors recall. The child had a fever. He was vomiting and had diarrhea. These were textbook signs of Ebola. But 80 percent of pediatric patients here have similar complaints, usually pointing to malaria or a severe stomach bug, doctors say. They further screened the boy for the virus by asking his father some questions. Any travels? Any funerals? No, no, he said.

The boy was taken to a general ward inside the cramped hospital, which overlooks Destruction Bay on the city’s east end. The hospital’s open windows were covered by sheets to block out the sun and the smell of burning trash. A sign painted in red by the hospital entrance read, “Water from the well in the hospital compound is unsafe for drinking.”

Two days later, the boy’s gums started to bleed. He was transferred to the hospital’s isolation ward. A day later, his lab tests came back. He had Ebola. Doctors delivered the news to the boy’s stepmother and asked again about his travels. The stepmother said the boy had attended his grandmother’s funeral in the provinces.

The father had lied to us, said Sara Hommel, a German pediatrician with a foreign aid group, clearly upset.

She couldn’t understand it. Other doctors, too, have complained about patients not being forthcoming about possible exposure to Ebola. But facing a disease with no cure, perhaps the father and others were afraid to admit the truth.

The hospital had remained closed for several days as the remaining hospital staff members demanded to be taught the infection-control measures considered essential to guarding against this unforgiving virus. “We are not going to rush back to work,” a hospital administrator said. “We want to be protected.”

The wait dragged on. Hommel and another German doctor, Noa Freudenthal, wondered how many cases of malaria or typhoid were going untreated. Ola During once had been filled with 250 patients. Where were these sick children now? Recently, a charity hospital tried to deliver a 2-year-old child suffering from cerebral malaria to the children’s hospital but was turned away. The gates were closed.

And then, one day last week, an infectious disease specialist from the University of California at San Francisco walked into Ola During. Dan Kelly conducted days of training, teaching staff members how to sanitize the floors and how to put on and remove the personal protective gear.

“Fear of Ebola is just permeating everything right now,” Kelly said.

He hoped maybe the training might instill a little confidence.

In the coming days, the children’s hospital is expected to reopen its metal gates.

The only question is whether patients will be too scared to come.

© 2014, The Washington Post