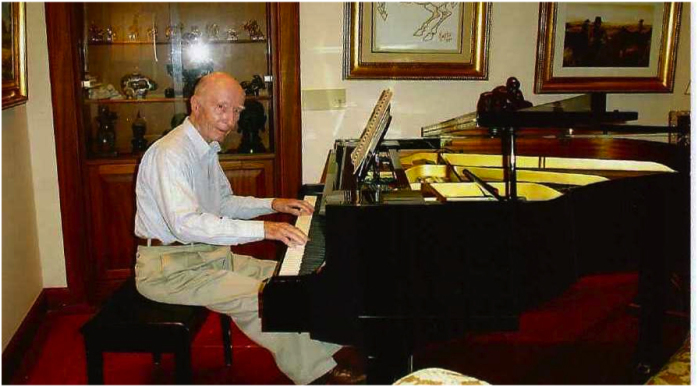

The children of friends he used to visit in Escazú say he liked to drive backwards down the hill in his Cadillac. He loved to play Sinatra, Rachmaninoff and Chopin on his piano. And he once crash-landed his single-engine Cessna 210 on a farm in Alajuelita. When emergency responders reached him, Richard “Dick” Johnson was quietly sitting on a tree stump, filling out his flight log.

Everyone who knew Johnson, who died at 91 on July 20 in Costa Rica after a long illness, has fond stories of a profoundly caring, energetic and ambitious man. He found success in Costa Rica as part of a first wave of expats from the United States following the Costa Rican revolution of 1948. That particular group mostly retained its U.S. identity while wholeheartedly embracing a new country, becoming just as much Ticos as they were North Americans.

“He was very warm, he took to people, liked people and was a courtly gentleman,” said James Fendell, whose father Jack Fendell was a representative of Hearst Corporation for middle Latin America and the Caribbean, and a good friend of Johnson’s. Both Jack Fendell and Johnson were involved in founding the American Colony Committee in Costa Rica.

“Costa Rica is very accepting of people from other countries as long as they’re gentle folk. Costa Ricans get along with people who are gentle and decent, and certainly Dick Johnson fit all of that,” James Fendell said.

Johnson founded the margarine and African palm oil products company NUMAR in Costa Rica in 1951 and later served as vice president of United Fruit Company in Boston, Massachusetts.

“He was an exceptional man, a very kind gentleman who was charitable and firm, but delicate,” said Humberto Pacheco, whose family considered Johnson a close friend.

Pacheco’s father-in-law, Dr. Mike Ortíz Martin, a pediatrician, and his wife Janet Basta Unkel, once jumped into a NUMAR truck with Johnson and the kids to visit a cacao farm they bought in Sarapiquí on a whim. Of course, the two knew nothing about the farm before they purchased it, and the venture was the source of more than a few laughs at parties when they had realized it was a flop. From then on they called each other “socios” (partners).

From small-town Midwesterner to naval captain

Johnson was born on June 12, 1923 in Doland, South Dakota, a Midwestern town with a population at last count of 180. Doland also was the hometown of former U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had a hand in helping get Johnson’s margarine company off the ground. Humphrey’s father ran a pharmacy in the small town. Johnson’s father ran the local grocery store, selling everything from “bananas to shoes,” according to Johnson’s second wife, Judy Johnson.

Richard Johnson was 2 when his mother died, and he was sent to live with his aunt on a farm in De Smet, South Dakota. There, his aunt, who was married to a banker, made sure Johnson received a good education, including piano lessons. Ten years later, she bought a car but couldn’t drive it. So Johnson drove her around at the age of 12.

Johnson enrolled in the Michigan School of Technology, where he completed three years of studies in electrical engineering. A year after the U.S. declared war on Japan in 1941, Johnson joined the U.S. Navy. He served four years in the Pacific, rising from engineering officer to captain. His naval service took him around the world – including through the Panama Canal – and during a brief port of call in California, he met his first wife, Elissa, an Armenian-American who looked and sang like Judy Garland.

After retiring from the Navy, Johnson decided to finish his engineering studies, enrolling at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He graduated in 1948. In Los Angeles, he met a Costa Rican entrepreneur named Silverio Chaverri, who convinced him to travel to a banana plantation Chaverri owned in Sierpe, in southern Costa Rica. In February 1948, he and Elissa – now married – moved to Sierpe, where they lived and worked for eight months before moving to San José.

Historically, 1948 was an interesting year for Costa Rica, but also for the Johnsons. Dick often told wild tales of the family’s early adventures in the Southern Zone, Judy Johnson said.

“They met somebody from Costa Rica [Chaverri], had a few drinks, and the man asked if they wanted to come to work in Costa Rica. At the time, they thought Costa Rica was Puerto Rico,” Judy Johnson recalled with a chuckle. “The man was very wealthy, but he wanted to live in Spain. So, they came here and it was very funny because somehow they ended up on a train going south. They were in a suit and hat, and they had to walk down the train rails because the man forgot they had arrived and there was nobody to pick them up.”

When Dick and Elissa Johnson finally arrived in the tropical heat of Sierpe, the refrigerator was broken. Dick Johnson spent the next three hours repairing it “just to have a drink of whiskey,” Judy Johnson said. “A few hours later when the ice came out, they celebrated with a drink.”

Engineering success

Back in San José, Johnson saw opportunity to start his own business. He traveled to the U.S., where he found two investors willing to back a new venture – the first margarine plant in Central America. NUMAR – a combination of the words “nutritious” and “margarine” – started production in May 1951.

NUMAR began in a garage in San José’s Barrio Luján, and according to Judy Johnson, it lost money for an entire year while Dick Johnson tried to learn everything he could about margarine. Frustrated, he traveled again to the U.S. to tell his two majority shareholders the project was a failure. But they sent him back to Costa Rica with an order to keep going, and to spend more money on advertising. At the time, Johnson was working as the company’s engineer, sales manager, mechanic, and any other duty that was required.

One of NUMAR’s biggest barriers at the time, however, was the Costa Rican demand for butter. No one trusted this strange, new palm oil derivative called margarine. At one point, Johnson was called before the Legislative Assembly to defend his product. Lawmakers responded by ordering him to add yellow dye so that customers would know it wasn’t butter.

But little by little the demand for margarine began to grow, and NUMAR’s business eventually started to thrive, along with the demand for African palm oil. In 1965, United Fruit Company in Boston bought NUMAR, and Dick and Elissa Johnson moved to the U.S. East Coast, where they would live for three years. In Boston, Johnson helped expand United Fruit’s operations, acquiring stock in companies like Baskin and Robbins and A&W Root Beer, according to Judy Johnson. He became vice president in 1968, and helped develop agricultural exports, working with labor leader and civil rights activist César Chávez, whom he grew to know well.

But Elissa Johnson didn’t like Boston much. The family returned to Costa Rica, where Dick assumed the role of vice president of several of the company’s operations – including palm oil plantations and factories – in Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

In 1984, when United Fruit changed its name to Chiquita Brands International, Johnson and colleagues began producing bananas for export, mainly to the U.S. He retired in 1987 at 64.

New chapters

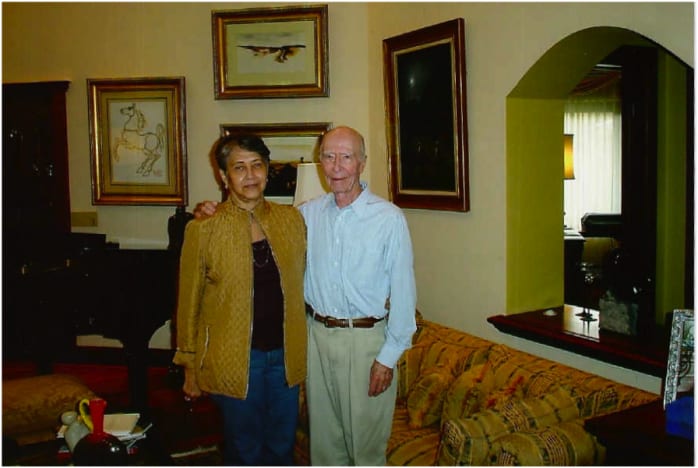

Johnson’s first wife, Elissa, died at a young age in 1980 after a long illness. They had been raising three kids, Richard, Michael and Janice. At a friend’s house, he met Judith Waugh, a Calí, Colombia-born British citizen who immigrated to Costa Rica in the 1960s, and whose late husband worked for the competition, Standard Fruit. Judy was raising three teenage boys of her own – Terrence, Phillip and Kenneth.

Dick and Judy were married a few short months later, in October 1980.

“I’m really glad. We really had a wonderful time. He was a very interesting person, with a lot of interesting facets. With his boat, his plane, whatever, he always wanted to do different things,” Judy Johnson said.

He was active in the American Colony Committee, the Costa Rican-American Chamber of Commerce (AMCHAM), where he served as president, the Rotary Club, and several other organizations. According to Humberto Pacheco, Johnson continued attending AMCHAM meetings until his health no longer permitted. “It was one of the loves of his life,” Pacheco said.

And so was the piano. His teacher was at least a generation younger, but that didn’t matter, Judy Johnson said. Johnson continued taking lessons all the way up to age 90, playing an array of jazz tunes for anyone interested.

A memorial service for Johnson was held last Thursday at Iglesia Don Bosco in San José.