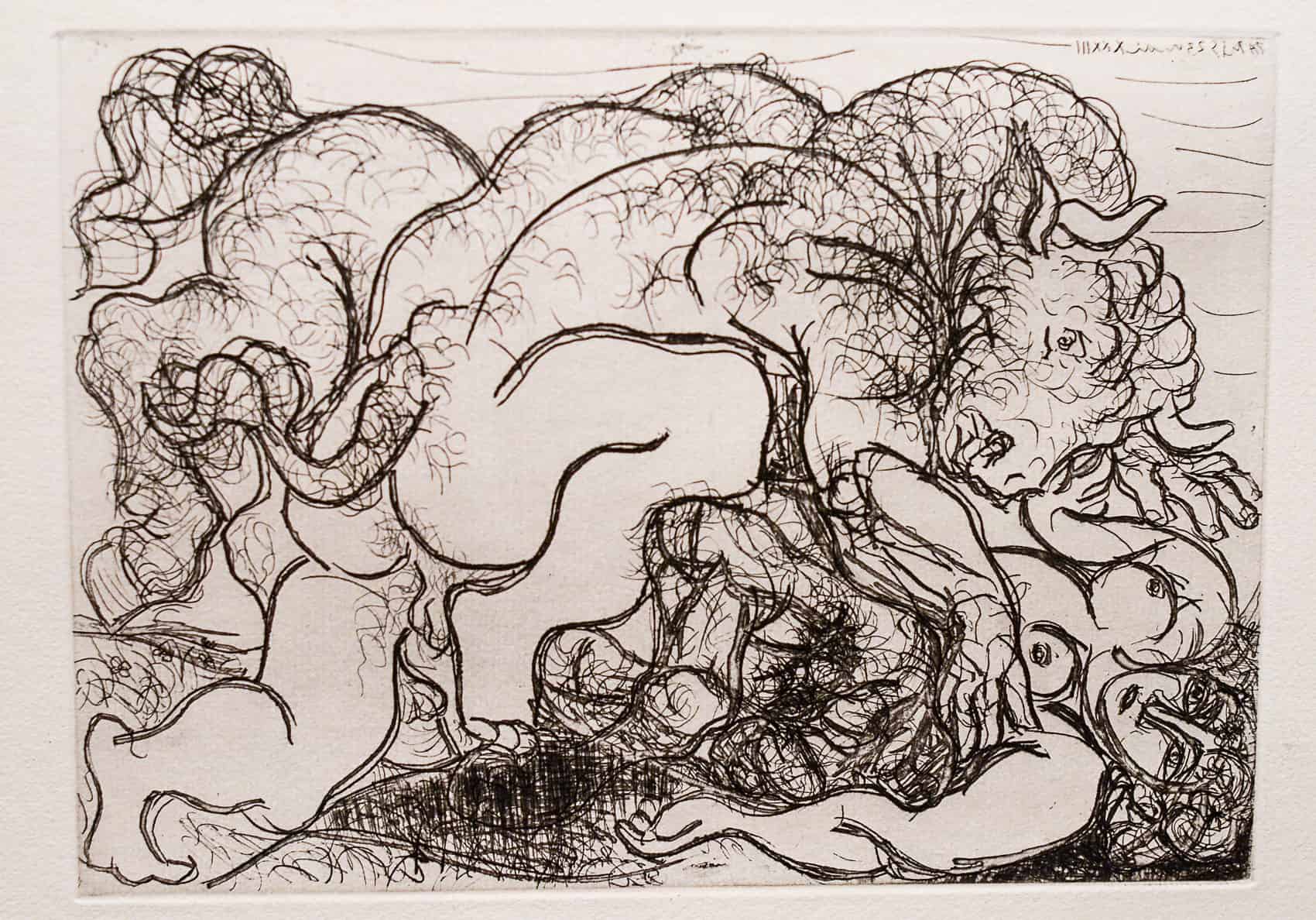

In the drawing “Minotaur Attacking an Amazon,” a hairy, naked minotaur wrestles a bare-breasted woman to the ground. His eyes are cold, but his hulking body arches with intent. The Amazon looks resistant, and she pushes a hand into his face, but it’s clear that her fight is hopeless. The image is vicious and unsettling, a blunt vision of sexual violation, and you might be surprised to learn that “Minotaur” is the work of Pablo Picasso.

“Minotaur” aptly represents “Herencia del Arte” (“Art Heritage”), a massive exposition now on display at the National Gallery in downtown San José. Showcasing 158 works of art on two floors of the Costa Rican Center of Science and Culture, “Heritage” is diverse, provocative and even shocking. Like a survey course in the history of visual arts, “Heritage” rounds up artworks ancient and postmodern, pious and pop, drawn and sculpted and photographed and projected. If this wing of the former penitentiary was buried in the ground and discovered millennia hence, future generations would learn a great deal about civilization so far.

The exhibit marks the 20th anniversary of the National Gallery, and in publicity materials, the Gallery is pushing the exhibition’s famous contributors: Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas, Andy Warhol and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The public loves an old master or two, and such heavy-hitting names are welcome in Costa Rica, which doesn’t have a lot of world-famous art. (We get some recognition, yes, but we’re short on Mona Lisas). Because everyone knows “Guernica,” or Degas’ ballet portraits, it’s nice to see some rarer works, such as “Minotaur.”

But that’s nothing. As far as collecting is concerned, the curators of “Heritage” have outdone themselves: In one room you’ll find a Burmese Buddha bust, a papier-mâché face from Bhutan (compete with bulging third eye), and ghostly Nepalese masks made from wood, human hair and “sacrificial materials.” You can also see a range of African masks and statuettes, including a rainbow-colored gazelle from Mali.

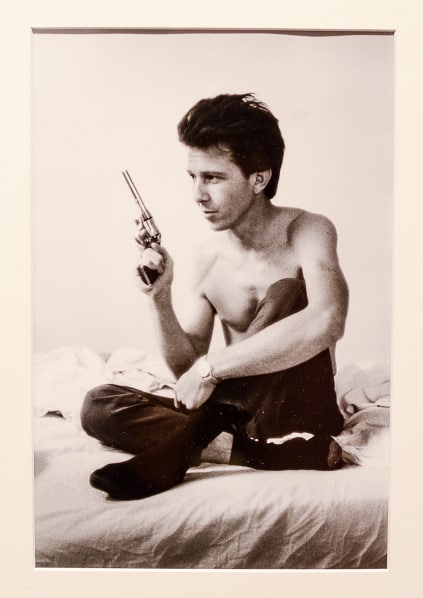

The antiquities alone would leave guests satisfied, but “Heritage” is encyclopedic in its presentation: You can see the stark photojournalism of Larry Clark, the haunting sculptures of Vanessa German, and Eric Le Maire’s “The Volcano,” a conical pile of steaming dirt. Like a dose of MOMA injected into the heart of San José, much of “Heritage” is aggressively avant-garde.

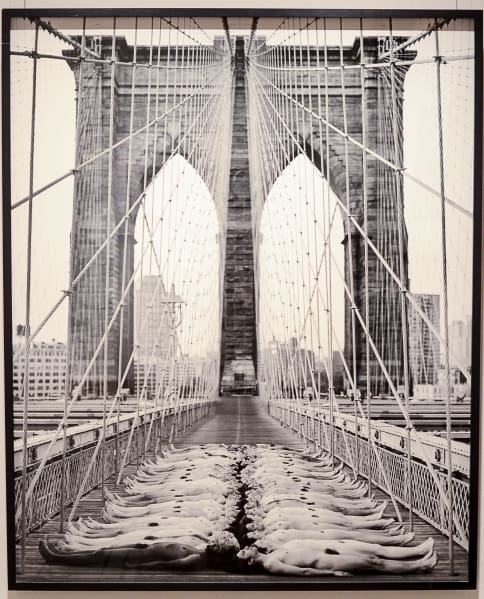

Part of what makes “Heritage” impressive is its overt nudity: Spencer Tunick has been photographing large groups of naked people since the 1990s, but Tunick is not the first artist one expects to find in Central America. His two large-format photos, taken on the Brooklyn Bridge and in Manhattan, show groups of disrobed people lying on the pavement, looking as peaceful as babies. Like Tunick’s portraits, the presence of nudity at the National Gallery is so overwhelming that you quickly adapt. A mature visitor will see the 16 sketches by Richard Guino – showing a range of acrobatic sex acts – and appreciate them for their aesthetic as well as their erotic imagination.

Art lovers in Costa Rica often complain that the nation’s creative scene is too conservative to take seriously. Ticos and Gringos alike gripe about the usual galleries with their bland, predictable fare. Many are tired of the same leafy landscapes, the same waterfall photographs, the same oxcarts and feel-good paintings of toucans. While I personally find this assessment unfair, it’s true that San José is no Amsterdam.

If anything, “Heritage” will stir the imagination, and both artists and art appreciators should benefit. “Heritage” is a remarkable crash course in artistic traditions, and a smart summary of contemporary art’s possibilities. “Heritage” isn’t careful or polite, as one would expect of the National Gallery; rather, it’s edgy and aggressive. Like “Minotaur,” the exhibition affronts its audience with uncomfortable content, so that the visitor is forced to feel something. That’s a good thing, and hopefully some milquetoast artist will stop by, feel inspired, and try a whole new approach.

Of the dozens of artists included, my own favorite was Geert Goiris. The photographer has two landscapes: “Liepeja” depicts an old concrete building sinking into gray water, and “Ministry of Transportation” shows a colossal and decaying structure built like a pile of Legos. Each photograph is plainly fatalistic, a celebration of ruins. Not everyone will share my love of tragic architecture, but that’s the real triumph of “Heritage”: There’s something for everyone.

“Herencia del Arte” continues through June 28 at The National Museum, Costa Rican Center for Science and Culture (former penitentiary), downtown San José. Mon.-Fri., 8 a.m. – 4 p.m.; Sat. & Sun., 9:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. Free. Info: National Gallery website.