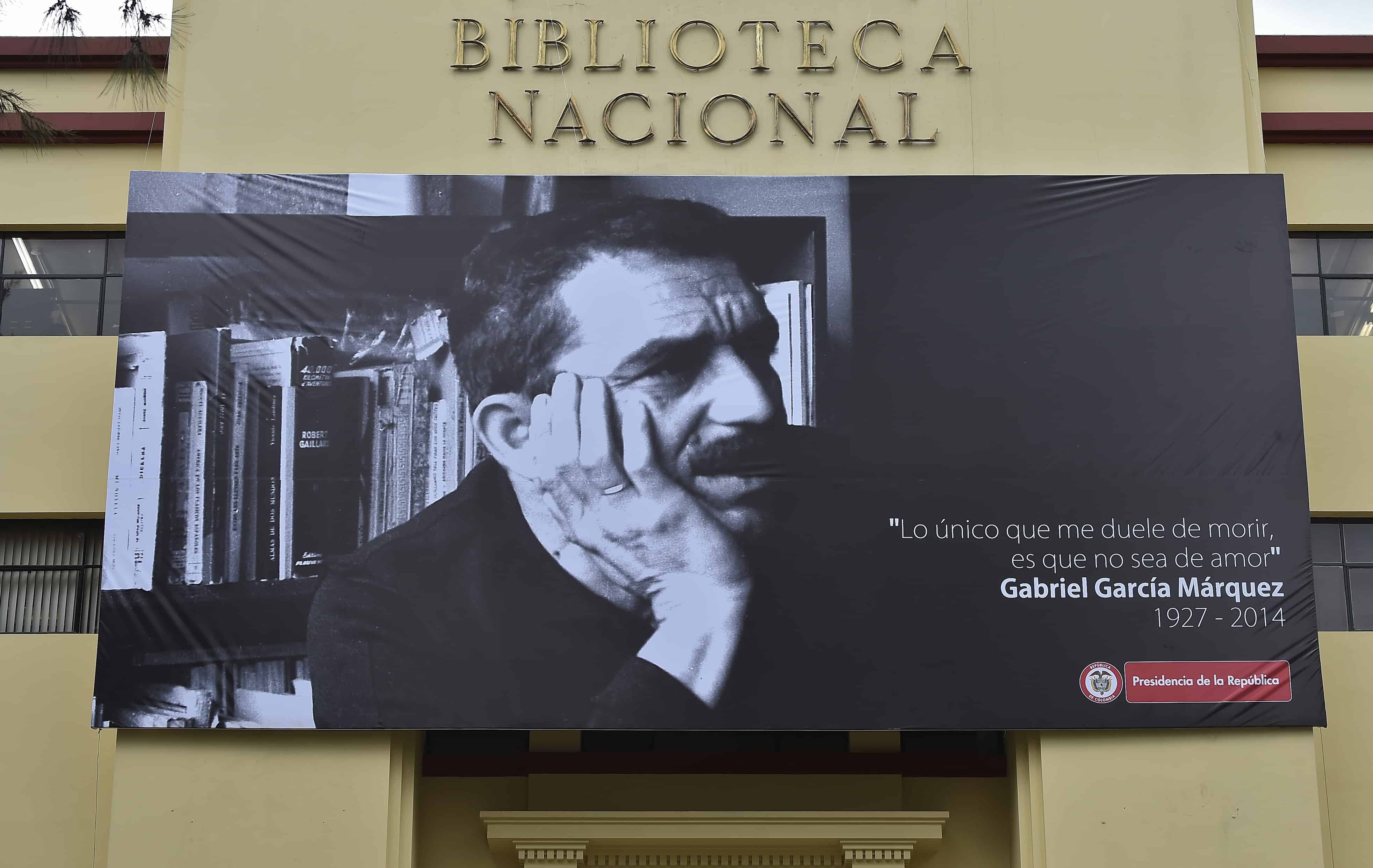

NEW YORK – Few contemporary writers and none from Latin America could match the scope of his influence or the radical inventiveness of his imagination. Affectionately called “Gabo,” Gabriel García Márquez, the Colombian Nobel laureate, journalist and author, was the most celebrated Latin American cultural export of his era. He died, at 87, on April 17, in his home in Mexico City.

His glamorous mystique — the houses and apartments strewn across Europe and the Americas, the glossy magazine profiles, the voluptuousness of his words — was offset by the author’s self-deprecating charm and humble back-story. The chasm between his socialist beliefs and the opulent lifestyle to which he ultimately grew accustomed attracted criticism, to be sure, yet his literary reputation never sagged under the weight of that paradox.

It was the 1967 publication and 1970 translation into English of his most famous novel, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” that vaulted the author to stardom. In that novel, the head of the allegorical Buendía family interprets the world according to his own perceptions. In a warped chronology of events, Macondo’s founding family is regenerated ceaselessly, through revolution, natural disaster and incestuous coupling. Translated into English by the peerless Gregory Rabassa, “One Hundred Years of Solitude” has sold tens of millions of copies worldwide. It gave exuberant voice to a region of the world that had previously been viewed as lush but inscrutable, best known by many North Americans and Europeans for its political instability and violence.

As in most of his fiction, in “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” the author said he sought to destroy “the lines that separate what seems real from what seems fantastic.” He did so with rapturous virtuosity, emotional insight and humor.

When The New York Times reviewed the book in 1970, the reviewer, John Leonard, described the work not so much as a piece of literature, but as an experience: “You emerge from this marvelous novel as if from a dream, the mind on fire. A dark, ageless figure at the hearth, part historian, part haruspex … first lulls to sleep your grip on a manageable reality, then locks you into legend and myth.”

While “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is a sweeping metaphor for Colombian cultural history — ghosts and modernity, colonialism and liberal reform, the introduction of railroads, the hegemony of U.S. corporate interests and military jackboots — the mythical town of Macondo itself was inspired by Aracataca, the Colombian village where García Márquez lived with his maternal grandparents until the age of 8. There, he absorbed his grandmother’s supernatural folklore. His left-leaning grandfather, a retired colonel, bequeathed the author a lifelong fascination with military and political power.

García Márquez was the eldest of 11 children (though his father, a pharmacist, also claimed several illegitimate offspring). In the fictional Macondo, the character Colonel Aureliano Buendía “had seventeen male children by seventeen different women and they were exterminated one after the other on a single night before the oldest one had reached the age of thirty-five.

He survived fourteen attempts on his life, seventy-three ambushes and a firing squad.” Such prose, at once epic and compressed, inspired an entirely new lit-crit lexicon, including terms like “Macondic.” Along with other Latin American writers, García Márquez helped to popularize the genre known as Magical Realism. But it’s the realism in his writing that’s often forgotten.

García Márquez was born in 1927, the year before the so-called “banana massacre,” in which striking Colombian workers for the United Fruit Company were crushed by the country’s military, who were anxious to forestall a threatened invasion by the U.S. Marines — a scenario he recasts in “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” He was a gifted student and attended a state-run boarding school. Later, under pressure from his family, he studied law at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá, but soon turned his attention to writing and never completed his degree.

When a Colombian Liberal Party member was assassinated, triggering La Violencia, a decades-long period of civil strife and violence that led to hundreds of thousands of deaths and displaced citizens, García Márquez gave up his legal studies completely and became a journalist. But he also read deeply the literature that would inform his development as a fiction writer. A particular obsession of young García Márquez’s was William Faulkner, whose mythical Yoknapatawpha County in the American South has been called a precursor to Macondo.

As a columnist in Bogotá in the 1950s, García Márquez wrote an expose about a naval shipwreck — the piece was later published in English as “The Story of A Shipwrecked Sailor” — that earned him the ire of the Colombian dictator, Gustavo Rojas Pinilla. To quell the fallout, the author’s newspaper sent him to Europe as a correspondent, but soon the government shut down the paper altogether. García Márquez kept writing fiction while working as a journalist and moving frequently, with spells in Venezuela, Colombia, New York and Mexico City. In 1958 he married Mercedes Barcha Pardo, who remained the unmovable pillar of his personal life until his death. The couple resided primarily in Mexico City and had two sons.

The left-leaning García Márquez wrote admiringly of Fidel Castro, eventually befriending the dictator. Both trouble and fame attached to him; the Colombian government planned to have him arrested for his political activities, Mexico offered him refuge, and the French awarded him the Legion d’Honneur. In 1982, he won the Nobel Prize for literature. Later, he would say that he put the prize money in a Swiss bank account and forgot about it for years; he eventually used it to buy the weekly magazine Cambio.

While he was lauded for his literary achievement, there were those among even his most ardent admirers who were disheartened by his politics, particularly his cozy relationship with Fidel Castro, who showered his writer friend with gifts that included a house on the outskirts of Havana. He, in turn, described Castro’s “childlike heart … political intelligence, his instincts and his decency, his almost inhuman capacity for work, his deep identification with and absolute confidence in the wisdom of the masses. …”

Critics and curious contemporaries reasoned that García Márquez was simply star struck by a man in uniform. Others theorized that that the writer was using the friendship to bend the dictator’s ear, and help Cubans leave the island or avoid harsh treatment.

According to a 1999 New Yorker profile by Jon Lee Anderson, García Márquez, “confirmed that he had helped people leave the island, and he alluded to one ‘operation’ that had resulted in the departure of ‘more than two thousand people’ from Cuba. ‘I know just how far I can go with Fidel. Sometimes he says no. Sometimes later he comes and tells me I was right.’ “

The White House, however, was not philosophical about the author’s political engagement, and for a period of years he was obliged to apply for a special visa to enter the United States. García Márquez seemed able to live with the moral contradictions posed by his friendship with Castro. But, given the complex dilemmas he assigned his most compelling characters, it’s hard to imagine that he was a man who would fail to grapple with that relationship.

Take the journalist-narrator of García Márquez’s slim, 2005 volume, “Memories of My Melancholy Whores,” who, nearing the end of his life, shares a ruthless self-analysis: “I discovered that I am not disciplined out of virtue but as a reaction to my own negligence, that I appear generous in order to conceal my meanness, that I pass myself off as prudent because I am evil-minded, that I am conciliatory in order not to succumb to my repressed rage. …” Such honest writing is what makes García Márquez’s characters so universally accessible, his fiction so humane.

But García Márquez also embraced popular imagery, using melodrama, romanticism and sentimentality unabashedly in novels like “Love in the Time of Cholera,” based on his own parents’ romantic history. He was a fan of telenovelas and boleros and even wrote a profile of pop-singer Shakira in 2002. The female characters in his fiction, while diverse, often fall into the category of dusky cat-eyed temptresses — the fiery Latinas of a good bodice-ripper. At the same time, child prostitutes and a scene during which a housemaid is raped while doing laundry, reveal a more pitiless and exploitative form of sexuality in his writing.

Through his fiction he undermined crude stereotypes of Latin Americans and informed the world about the region’s recent political history. The author himself once noted, “For Europeans, South America is a man with a mustache, a guitar and a gun.” Perhaps not so much anymore, thanks in large part to what García Márquez has left us.

Finnerty is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn. She has written for the New York Times Book Review, the Wall Street Journal and Newsweek, among other publications.

© 2014, Foreign Policy