Whether it belongs to a Pharaoh or a commoner, a recently discovered tomb is fun to open. A couple of archaeologists got their chance to do just that in San Ramón, 36 kilometers northwest of San José.

The 500-year-old tomb was unearthed in February in Santiago de San Ramón, where property owner Roberto Arias was leveling the ground with a bulldozer. It scraped a large, flat rock and revealed a hollow space underneath. When Arias took a closer look, he wondered if it might be a tomb, and sure enough, it was. By law, Arias knew, all archaeological discoveries must be reported and preserved. So he called the Judicial Investigation Police, which in turn alerted the National Museum.

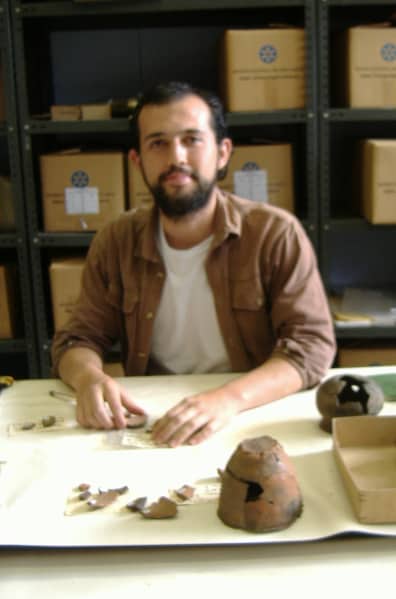

Archaeologists Ricardo Vásquez and Rony Jiménez received the assignment. They spent a week opening the tomb and carefully removing the bones of several skeletons and other artifacts that had been buried there for half a millennium. The tomb is likely from the late 1500s, around 1560, Vásquez said, which was around the time the Spaniards began exploring inland.

“We’re not just talking about a tomb,” he said. “We’re talking about a period when two cultures meet.”

Although much is known about life in 1500s Costa Rica from Spanish chronicles and surveying indigenous sites, this discovery is being closely studied. It measures 1.9 meters long by 70 centimeters wide, and is made of large, flat stones called lajas that were probably brought from a nearby quarry.

“The rocks fit together so well that the tomb had been sealed,” Vásquez said. “There was no dirt inside the tomb even though it lay underground.”

The bones found inside came from at least three people, and as many as six, the archaeologists reported. They had been carried to the spot, and over time had separated at the joints. There was no body tissue or fragments of clothing. Vásquez guessed that the remnants belonged to people who had died in their 30s — young for modern times, but old for back then, he said. In pre-Columbian days, the Huetar indigenous tribe inhabited the San Ramón area.

Vásquez has worked on many other tombs, but this one yielded some surprises, including glass beads, ceramic pots, a small copper bell and a scorched piece of corncob. The beads were a type made in Europe in the 16th century. The small jingle bell looked to be the ones the Spaniards would attach to harnesses. “The glass beads and the bell tell us that the Huetares knew and had contact with the Spaniards,” Vásquez said. Several ceramic pots — some intact, others in pieces — were also found.

Taking the tomb apart and restoring all the contents proved to be a grueling job for Vásquez and Jiménez. Using soft wooden and bamboo spatulas, they lifted, dusted and marked each find and had them packed for the National Museum’s laboratory for further assessment. The bones rest in a special carton in an archive with controlled air and temperature, but this is not their final resting place.

In time, the tomb will be on display at the regional museum in San Ramón. The other artifacts also will be on display.

Vásquez is excited about the find, and thankful that the builder stopped construction to alert officials of the tomb even if it meant delaying the construction of the house.

“Indigenous and other finds are part of our patrimony and must be preserved,” he said.