WASHINGTON, D.C. – Top U.S. lawmakers from both parties are urging the Obama administration to take a tougher line on Venezuela, which is violently cracking down on popular protests against the government of Nicolás Maduro. For some on Capitol Hill, though, the real target is Cuba.

These leading Republicans and Democrats are pushing back at a country that has been a constant thorn in the side of U.S. interests in Latin America in recent years.

Reps. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, R., Fla., and Eliot Engel, D., N.Y., have both called for the Organization of American States, which meets this week, to take a tougher line on the Maduro government’s treatment of peaceful protesters. Sen. Marco Rubio, R., Fla., has floated the idea of U.S. sanctions against Venezuelan officials involved in the crackdown, and even against the Venezuelan government itself.

But Venezuela hawks such as Rubio are making a second argument: tougher action against Venezuela represents a chance to undermine one of the key lifelines of the communist regime in Cuba, whose economy relies on heavily subsidized oil and other gifts from Caracas.

“The Cubans get free and cheap oil from the Venezuelans. So their interest is keeping this regime in place because they’re their benefactors,” Rubio told CNN this week. “And Cuba is clearly involved in assisting the Venezuelan government with both personnel and training and equipment to carry out these repressive activities,” he added.

A host of key lawmakers have long been skeptical of the Obama administration’s efforts to reach out to Cuba after more than 50 years of a U.S. economic embargo against the island nation. Obama’s efforts to loosen restrictions on travel and remittances, especially for Cuban-Americans, have provoked a backlash among lawmakers, like Rubio, who count on Cuban-American votes.

That perception was strengthened in December, when President Obama shook hands with Raúl Castro, the brother of Fidel and the current Cuban president, at the funeral of Nelson Mandela. That came just a month after Obama suggested the United States might need to rethink the embargo.

Rubio said in a passionate speech on the Senate floor Monday that he also wants normal relations with Cuba — “a democratic and free Cuba. But you want us to reach out and develop friendly relationships with a serial violator of human rights, who supports what’s going on in Venezuela and every other atrocity on the planet?”

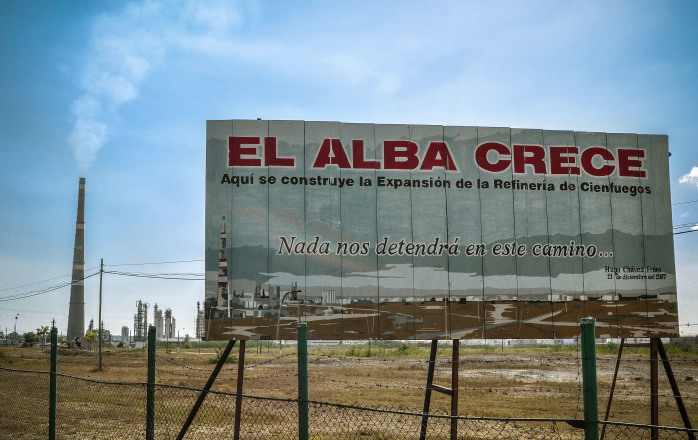

Cuba and Venezuela are linked as foreign policy challenges for many U.S. lawmakers because of the close ties between the two socialist regimes. Former Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chávez was an unabashed supporter of Fidel Castro, and helped ensure that Venezuela used its oil wealth to help prop up Cuba’s ailing economy. Chávez repeatedly sought medical treatment for the cancer that eventually killed him in Cuba, and the close relationship between the two countries has continued even as both have moved on to other leaders. Nicolás Maduro was one of the feted guests last summer when Cuba celebrated the 60th anniversary of the start of the Cuban revolution.

While Venezuela’s self-proclaimed “Bolivarian revolution” was modeled on Cuba’s, the South American oil giant replaced the Soviet Union as the island country’s main economic patron, underwriting the Cuban economy to the tune of billions of dollars a year.

Some estimates of the scale of Venezuelan support for Cuba, including more than 130,000 barrels a day of oil but also salaries for thousands of Cuban officials working in the country, suggest Caracas gives Cuba more than $10 billion a year, or between one-fifth and one-sixth of Cuba’s gross domestic product. That comes close to the level of economic support that Cuba received from the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, before the Soviet collapse abruptly ended Moscow’s economic aid to Fidel Castro.

In other words, some lawmakers believe, further unrest or even a change in the regime in Venezuela could represent a direct threat to the continued rule of Raúl and Fidel Castro in Cuba.

However, a lot has changed since the end of the Cold War. Cuba has slowly tried to reform its economy and find more than one “sugar daddy” to prop it up. Brazil, for one, is increasing investment and trade in Cuba, and just helped construct a major port not far from Havana. Cuba, recognizing the peril that reliance on Venezuelan oil poses for its economy, has also repeatedly sought to tap what it believes are abundant oil reserves in the Gulf of Mexico, but so far without success.

“Do you drive Cuba off the edge of the earth by strangling Venezuela? Nothing the United States has done in 50 years has caused that to happen in Cuba,” Julia Sweig, a Latin American expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, told Foreign Policy. “My expectation is that Cuba has been planning for this for a long time, and even if they’re not 100 percent ready, they are prepared enough,” including deeper economic ties with Brazil, the European Union, Canada, and China, she said.

Oil is at the heart of Venezuela’s support for Cuba, but it is also at the heart of Venezuela’s own woes. Much of the popular anger in Venezuela is a reaction to the government crackdown on students. However, widespread dissatisfaction with the Maduro government’s economic mismanagement has prompted even the middle class — hammered by soaring inflation, empty store shelves and a cratering currency — to join the protests. The New York Times captured the mood this week talking with one such protester: “Look. I’ve got a rock in my hand and I’m the distributor for Adidas eyewear in Venezuela,” Carlos Alviarez told the newspaper.

RECOMMENDED: Adiós, El Chapo: Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto might want to think twice about popping the champagne.

And that economic malaise is due in part to the systemic mismanagement of Venezuela’s oil wealth over the past 15 years. Blessed with the largest oil reserves in Latin America, and the second largest in the world, Venezuela has struggled to attract the foreign investment needed to increase oil production, especially in challenging oil fields laden with thick, heavy oil.

Production has remained constant, at about 2.3 million barrels per day in recent years, in part because rampant inflation has made it hard for foreign firms to boost output there and partly because the Chávez and Maduro regimes have used oil income to underwrite expensive social programs at home, to the detriment of productive investment in the industry.

Exports, which account for about half the Venezuelan budget, have plummeted since the advent of Chavismo. Venezuelan oil exports peaked in the late 1990s at about 3 million barrels, but have since fallen to about 1.7 million barrels a day. Additionally, some 400,000 barrels of that export total are sent to Caribbean nations under preferential terms, further eroding Caracas’ potential earnings.

While Rubio and others rail at the State Department for not taking a tougher stance on Venezuela, another office in Foggy Bottom did take one important step this week that could ultimately deal a big economic blow to Maduro and the Venezuelan government. The State Department’s Inspector General determined that its environmental review of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline suffered no conflict of interest.

That removes one of the last potential obstacles for the Obama administration to finally greenlight the pipeline that would carry almost 800,000 barrels a day of heavy crude oil from Canada to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The biggest loser if Keystone is built? Venezuela, which currently exports about 800,000 barrels of heavy oil a day to the United States to keep those refineries humming.

John Hudson contributed to this article.

© 2014, Foreign Policy