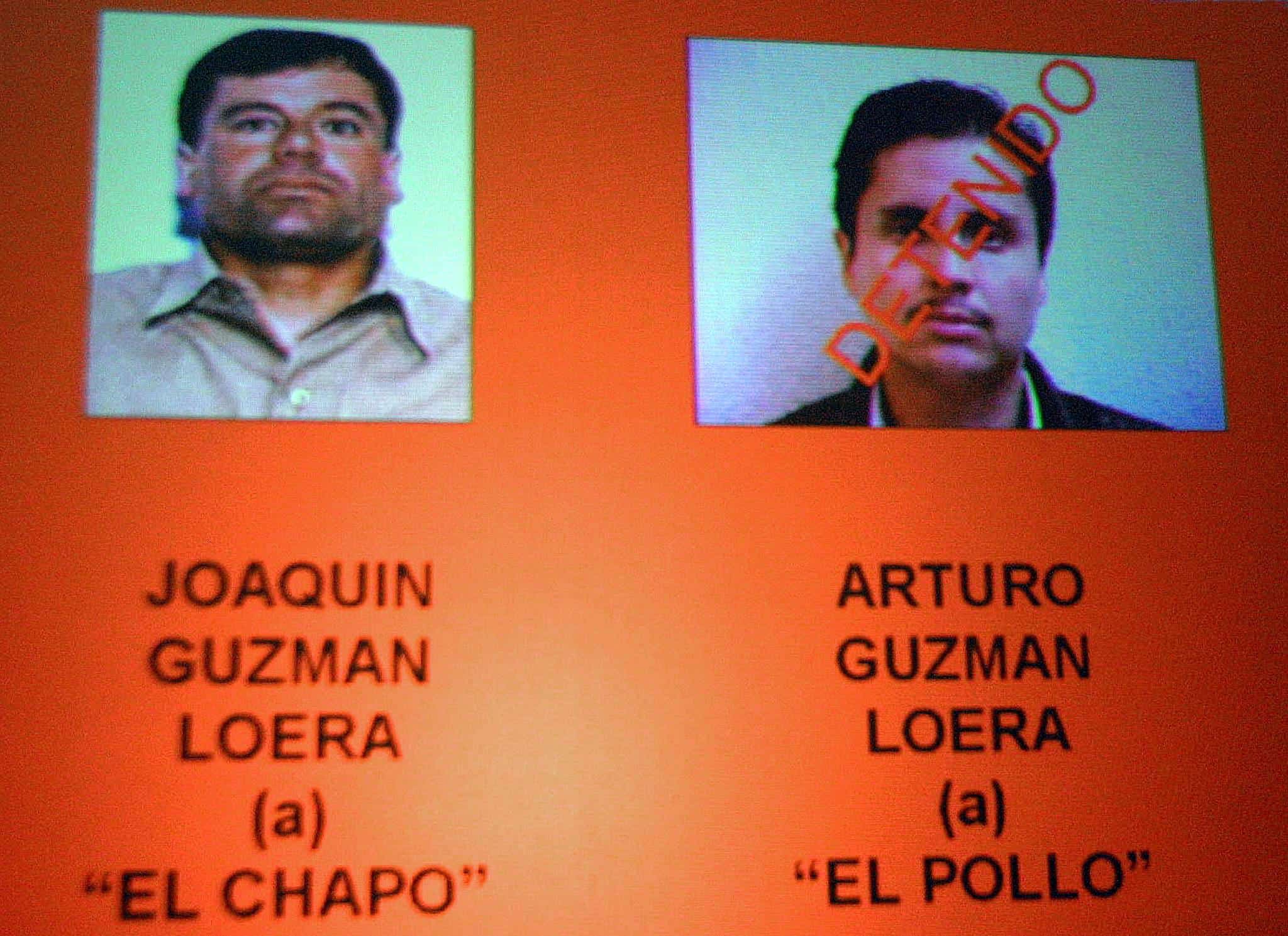

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Seven federal districts in the United States have brought indictments against Mexican cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, setting off a competition to be the first to prosecute the man U.S. officials had described as “Public Enemy No. 1” before his arrest this past weekend.

The number of cases against Guzmán, head of the powerful and violent Sinaloa drug cartel, show the breadth of his multibillion-dollar empire. He has been indicted in San Diego, the Southern and Eastern districts of New York, Chicago, Texas, Florida and New Hampshire.

But Justice Department officials said it is an open question whether Guzmán, who was the world’s most-wanted drug lord, will ever be prosecuted in a U.S. courtroom.

“There’s an old saying that possession is nine-tenths of the law,” said Stephen Vladeck, a professor of law at American University in Washington and an expert in extradition law. “But in this case, it’s actually closer to 10-tenths, because if they want to go first, they can. If Mexico wants to prosecute El Chapo under their own laws, it’s their right to do so. And all the U.S. can do at that point is take a number.”

The Mexican government formally charged Guzmán with cocaine trafficking and organized crime, officials in the Mexican Attorney General’s office said Monday. The crime boss is facing at least eight apprehension orders dating back to his escape from prison in 2001.

A judge assigned to the case has until 3 p.m. Tuesday to decide whether to initiate a trial or release him, the prosecutor’s office said. Guzman has been assigned an attorney, Óscar Quirarte, who has not yet spoken about the case.

Guzmán “was the number one target we were going for in the world,” said a senior Drug Enforcement Administration official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss an open case. “No one was as sophisticated. No one was moving the volume of narcotics he was moving, not just in the United States but worldwide.”

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, which took office more than 15 months ago, has extradited fewer people to the United States than the previous Mexican government.

In the last four years of the administration of Felipe Calderón, Peña Nieto’s predecessor, the number of extraditions to the United States topped 100 per year twice, reaching a high of 115 in 2012. That number fell to 54 last year, the first full year of the current government.

“The fundamental reason for extradition is to have firsthand information,” Jesús Murillo Karam, Mexico’s attorney general, said in an interview this month. Karam said that under Peña Nieto, intelligence-sharing with the United States is more reliable, so “that requires fewer extraditions.”

Mexican authorities say they cooperate closely with U.S. law enforcement officials and are willing to send criminals back to the United States. But they increasingly want people who commit crimes in Mexico to serve their time in Mexican prison before being sent to the United States. That way, Mexican authorities have full access to the intelligence generated from suspects and can show that the country’s judicial system can reliably hold top criminals.

Guzmán, who is being held at a maximum-security prison called El Altiplano in Almoloya de Juárez, once before slipped from the hands of Mexican law enforcement. He was captured in Guatemala in 1993 and sent to Mexico’s high-security Puente Grande prison. But he escaped in 2001, on the eve of his extradition to the United States, allegedly spirited out in a laundry cart.

Obama administration officials said there are likely to be lengthy negotiations to decide which country tries Guzmán first.

“The decision whether to pursue extradition will be the subject of further discussion between the United States and Mexico,” said Justice Department spokesman Peter Carr.

One of the last major cartel bosses to be extradited to the United States was Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, who ran the Gulf cartel and was sent to the States in 2007. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison, a term that some Mexican officials thought was too short. U.S. officials were upset when another drug boss, Rafael Caro Quintero, convicted of the murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, was freed from Mexican prison last year after 28 years behind bars.

Cárdenas committed “much more serious crimes than Caro Quintero,” Karam said, but received a shorter sentence in the United States.

In 2009, when Guzmán and 35 other cartel members were indicted in Chicago on heroin and cocaine trafficking charges, Patrick Fitzgerald, then the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, called the cases the “most significant drug importation conspiracies ever charged in Chicago.”

Three years later, Guzmán and 23 other members of Sinaloa and other cartels were indicted in El Paso.

“Murder and kidnapping, money laundering and drug trafficking are the four corners of this organization’s foundation,” U.S. Attorney Robert Pitman said. “For years, their violence, ruthlessness, and complete disregard for human life and the rule of law have greatly impacted the citizens of the Republic of Mexico and the United States.”

Five other federal prosecutors have made similar announcements.

Julie Tate contributed to this report.

© 2014, The Washington Post