I arrived nearly two hours early to the small campus of Veritas University to meet Luis Chaves. Although I didn’t want to rush him, I decided to text him. Take your time, but I’m available when you’re ready. Chaves replied back almost immediately. He was on his way.

Minutes later, a compact 44-year-old with squinty eyes and whiffs of facial hair was sitting across from me. His dress was casual. He seemed in good humor.

We moved to a campus snack bar, where Chaves grabbed a refreshment and we sat down at the table.

“So,” Chaves said, “what do you want to talk about?”

He said this in a curious tone, as if he couldn’t imagine why a reporter would call him up. That seemed odd, considering that Luis Chaves is the most famous living poet in Costa Rica.

*

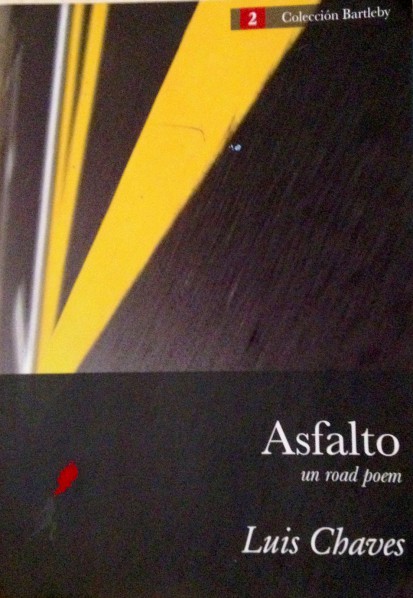

Becoming an important Costa Rican writer is a unique challenge, and this is how Chaves did it: He came out of nowhere and ignored the barriers that separate poetry from prose. To understand what that means, it helps to have read “Asfalto,” his most renowned work.

In “Asfalto,” a man and a woman take a road trip. They watch the highway through their windshield. They listen to The Kinks on their stereo. They stop at gas stations and motels. They sleep badly. In one ominous scene, we watch them through a surveillance camera. The chapters are short vignettes, but we soon realize that their relationship is falling apart. The unnamed characters are doomed: “In the old wallet shaped by buttocks, a photograph of better times. The two of them in a park in another country. The photo in which she will forever gaze, not at him, who embraces her, but toward the unknown person who took it.”

The full title is “Asfalto: un road poem,” and the book takes some cues from Jack Kerouac. But Chaves is also tougher, terser and more biting than his beatnik predecessors. At exactly 100 pages, “Asfalto” packs a wallop. On the page, “Asfalto” looks like prose; there are no stanzas, no line-breaks, no obvious rhyme or meter. But the book is terse and high-impact, like poetry.

This balance Chaves eloquently strikes is the reason he has become one of the most exciting authors in Costa Rica, which he seems almost oblivious to.

“I just like to write,” Chaves said. “I don’t care about the genre. It is up to the editors to decide where (a book) goes, but I give each one the same care.”

Acquaintances say Chaves seemed like a fairly ordinary kid. His father was an amateur boxer, and Chaves was also an athlete. He studied agronomy at the University of Costa Rica, and he worked an office job. He always arrived on time, and seemed destined for a cubicle.

But something happened, that nobody (Chaves included) has been able to explain. In short, he became deeply interested in creative writing. To the surprise of many friends and relations, he abruptly turned away from agronomy – and the stable career everyone expected for him – and began to write poetry.

He participated in a writing workshop and developed his craft. He paid bills by beginning a career as a freelance translator. He used his natural discipline to practice his writing, and he traded work with fellow writers. He cultivated a friendship with César Maurel, a poet and visual artist originally from Paris, France.

“It was very informal,” Maurel told me recently. “(Chaves’ writing) is very narrative, very modern. It’s more natural.”

In 1996, the press Editorial Guayacán published Chaves’ first collection, “El Anónimo” (“The Anonymous”). A year later, Ediciones Espiral published his second collection, “Los animals que imaginamos” (“The Animals We Imagine”). This second book won the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize for Hispanic American Poetry. His 2001 book, “Historias Polaroid,” was shortlisted for a major Colombian literary award. By the time Editorial Germinal released his fourth book, “Chan Marshall,” in 2005, Chaves had established himself as a wellspring of superlative verse. “Chan Marshall” won the international III Fray Luis de León Prize for Poetry.

When Chaves started to contribute to La Nación, he wrote largely about sports – his lifelong passion. Poetry and athletics don’t often mix. Yet Chaves feels they are the perfect marriage. “I’ve had this dilemma,” he said. “I like the aesthetics of sports. I don’t see a difference between a great poem and a great play in a soccer game.”

*

Talking to Chaves, it turns out, is much easier than talking about Chaves. Of the dozens of people I contacted to discuss the author’s work, only a few agreed to be interviewed. Many said they didn’t feel qualified.

“I can’t speak with you on the record,” said an old friend of Chaves. Many others followed suit. The very idea of poetry intimidated them. During the week of National Poetry Day, celebrated on Jan. 31, readings were held throughout San José, including various bars and the National Library. But people were reluctant to opine about Chaves.

“I just don’t feel comfortable,” said one poet. “It’s hard to describe.”

Costa Rica has an active literary scene, quiet as it appears. Most foreigners would not realize this, because most of the writing exists only in Spanish, and even celebrated authors are unknown outside the country.

Yet iconic figures still exist: Manuel González Zeledón (pen name “Magón”) wrote stories at the turn of the century and founded the newspaper El País; today there is a Magón National Prize for Culture, awarded last month to poet Julieta Dobles Yzaguirre. One of Costa Rica’s all-time greats, Carmen Naranjo, served as ambassador to Israel and earned high praise all over the world.

Chaves holds a special place here, and his work crisscrosses through multiple genres. In recent years, he has authored the books “El Mundial 2010,” a nonfiction account of the 2010 World Cup, and “300 páginas,” a collection of columns and reportage. He has published broadly in literary journals and edited them as well. He continues to write regularly for La Nación. He even maintains his own blog, mysteriously called Tetrabrik.

He is fairly young and accessible, yet his style is also challenging and even colloquial: In “Asfalto,” the characters use the famously informal phrase “mae” (“dude”) in their dialogue. Chaves is a major figure in Costa Rica’s literary development, which, in its minute way, is kind of like being a celebrity.

*

When I asked him about the popularity of his work, about whether he felt a responsibility as “one of the leading figures in Costa Rican poetry,” he became dismissive.

“I don’t have any control over that,” he said. “I don’t think it’s something you look for. It has nothing to do with what I’m doing.”

Chaves leads a fairly simple life. He is married with two young daughters. For the past two years, he has worked in marketing for Veritas’ School of Film and Television. When I receive press releases for the school’s screenings and lectures, it is Chaves who sends them to me. The poet teaches writing courses and continues to do translation work on the side.

When I asked Chaves about his writing process, he was nonchalant: “I’m not methodical or disciplined. There are times when I’m just reading, not writing. Sometimes I just write bits and pieces. Sometimes there are a few weeks when I write almost every day, an hour I can steal from work or family. I have a notebook. But in general I use it to jot down ideas and phrases that I can develop later on the computer.”

In truth, Chaves is not a household name. He has no agent; as few Costa Rican authors do. He has no publicist and no prepared leaflet about his life and work. Most of his publishers are also friends and colleagues. Even finding his book can be a challenge: When I tried to find a copy of “Asfalto,” I visited Libreria Internacional, one of Costa Rica’s most popular chain bookstores. The clerk only could find a single copy of one of Chaves’ many titles, and the volume took about four days to ship.

But neither can Chaves deny his impact on young Costa Rican readers and writers, who are inspired by his youthful, contemporary style. He is not writing about the sleepy Costa Rica of yesteryear, but the country as it stands now.

“Luis Chaves has become a watershed,” says David Monge, an aspiring poet who runs a popular writing workshop in Alajuela. “He touches everyday topics with plain language … and poetic image. His works have influenced a new generations of writers, thus becoming a new paradigm of Costa Rican literature.”

Monge credits an explosion of small presses, which have made publishing easier. “These publishers have come to give voice to a more underground and experimental literature – hence Chaves, with works that are outstanding and at an international level.”

Chaves recently received a grant from the Culture Ministry to write his first short story collection; another new genre for him. If the book is successful, he could attract an even broader readership. His face recently graced the cover of “Buensalvaje,” a major Costa Rican literary review, accompanied by an unedited diary of 38 days of his life. He has published in such countries as Spain, Germany and Argentina. For readers of this paper, the most pressing question is this: Will Chaves ever be translated into English?

“Well,” Chaves said, shrugging, “that depends on whether someone is interested in translating it.”