Costa Rican biologist Eduardo Carrillo, 45, saw his first jaguar on May 7, 1990. Leading 10 students from his natural resource management class on a research trip to the Corcovado National Park, on Costa Rica’s southwestern Osa Peninsula, he came across a tell-tale sign: the rough trail of a sea turtle leading into the beachside forest. Large cat prints overlaid the turtle’s, which did not return to the sea. Sure enough, a partially mutilated leatherback turtle lay dead just inside the jungle.

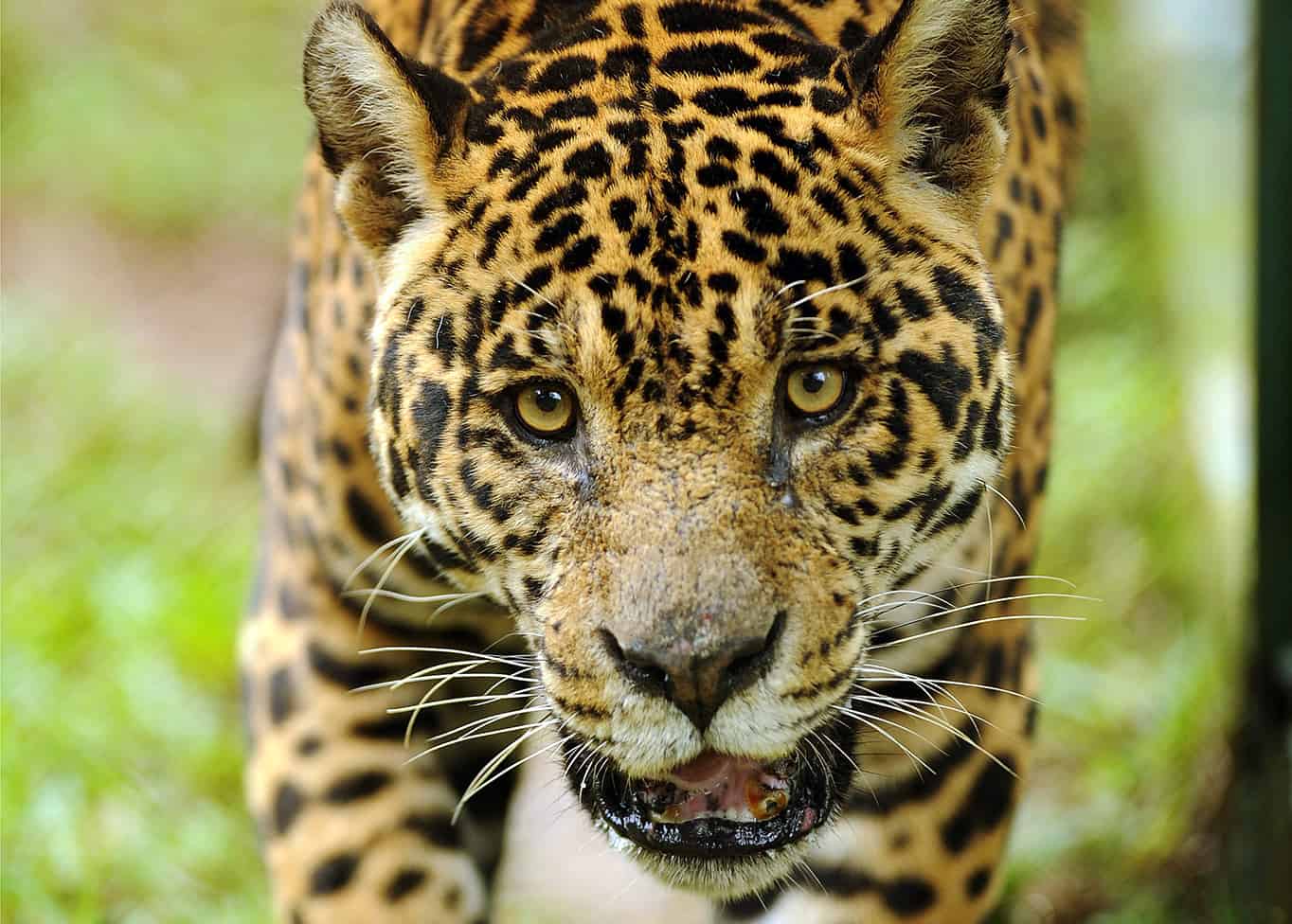

Carrillo’s group returned to the beach, where a student spotted a distant shape moving toward them along the shore. Taking cover behind a fallen tree, they watched as the shape moving intently along the sand slowly materialized into the unmistakable image of a jaguar. Trotting behind came a cub.

Carrillo, who stood still and brazen in front of the tree, clicked a photo as the two passed by. The mother cat snapped her ears back and growled, the cub scurrying under her legs as she crouched lower. After a moment, the jaguar continued on, disappearing into the forest, leaving Carrillo a changed man. “That was the moment that I decided I wanted to study jaguars,” he said.

In the nearly 17 years since, the genuine and bespectacled biologist has dedicated his life to studying the feline, which still graces a few Costa Rican jungles. His research, published in scientific journals and relied upon for documentaries by National Geographic and others, has earned him worldwide recognition.

Working with both the jaguar and the white-lipped peccary – the jaguar’s principal prey – counting tracks and using camera traps for photographic evidence, Carrillo, fellow researchers and his students have calculated that between 40-50 jaguars remain in the expansive Corcovado park, one of the country’s largest protected areas. In addition, jaguars also roam forests in the northwestern province of Guanacaste, the southcentral and Caribbean region of Talamanca, and are making a comeback in the Pacific coast’s Nicoya Peninsula.

His research shows how heavy hunting pressure in Corcovado was killing off the peccaries and forcing jaguars onto neighboring farmland, where they attacked cattle, and were killed by protective farmers.

Former Environment Minister Carlos Manuel Rodríguez (2002-2006) spent time in the field with Carrillo, and “took on our research like a flag,” proceeding to hire 50 more park guards for the Osa Peninsula, Carrillo recalled.

Sitting in his cramped and cluttered bunker of an office at the National University campus, in the northern Central Valley city of Heredia, Carrillo’s pride in his research gave way to serious concern as he talked about the future of jaguars, and conservation in general, in Costa Rica. Excerpts:

TT: What is it about the jaguar that has you so interested?

EC: The jaguar is an indicator species. You can say that a forest where you find jaguars is an ecologically healthy forest. In any Latin American, neotropical country, you can’t study all the species, because there are thousands and thousands. But you can focus on one or two, or ten maximum, that can tell you what the health of that ecosystem is. Where there are jaguars, there’s everything else. If we maintain a place with a healthy jaguar population, everything else is okay.

What are you working on right now?

What we are going to do now is put the cameras back (in Corcovado and Guanacaste) to compare what we found in 2003 and 2004 with what we have now, after having put a stop to the hunting. (In the data from 2006) the peccary populations do show an increase, but not the jaguars. But the predator’s response is always slower. It will probably be three or four more years until we know.

When you were getting started, it was difficult to get funding.You said one of the reasons you felt you didn’t get support was because you are Latino.What did that have to do with it?

In our field – and I’ll be frank with you – nobody is a prophet in his own land.

Here, people think scientists come only from outside the country, and they’re Gringos or Europeans. They don’t see the national as capable of science. I’ve got about 20 scientific articles published in the best journals in the world, and that doesn’t count the articles in popular magazines or videos I’ve done with the BBC or National Geographic.

We are now recognized on the international level, but still it seems like it doesn’t penetrate to the national level here, where people think that a scientist only wears a white coat and works in a laboratory.

We’ve maintained this project for many years and we’ve always been able to raise our own funds. The university gives us this space, and my salary. All the equipment you see here, absolutely all of it, has been bought with funds garnered elsewhere. In fact, we just received financing for another two years of the project from The Nature Conservancy, by way of the National Biodiversity Institute (INBio).

This is a constant struggle for financing. For example, to keep my research assistant, I have to look for a salary.We just got a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and that’s where his salary will come from. But don’t imagine it’s a big salary. It’s $500 a month, but subtract 45% for taxes and he earns about $250 a month.

I say this so you see that we’re not doing this for the money.

What is the reason you do it?

Because I believe it is necessary to generate knowledge that allows us to make educated decisions to maintain the species that live in the world. It’s that simple. Sometimes we think that human beings are totally apart from nature, but we are part of nature and we are dependent on nature.

When I hear politicians talking about conservation in this country, and see that in Corcovado there are one or two park guards running to put toilet paper in the bathrooms – it’s a lie. We’re not carrying out conservation.

Right now, we are talking about a water crisis here in Costa Rica, and nobody stops to think that it might be related to all the logging we have done in the past, and that’s why there’s not enough water. Then you have the foolishness of people wanting to open up forests to logging again in Costa Rica, talking about 125,000 hectares (309,000 acres) per year, and one says, Jesus, this is where we’re at?

Who is proposing these cuts?

The government. The Environment and Energy Minister (MINAE). That’s the contradiction, and they aren’t paying attention to what we already know. Corcovado isn’t big enough to maintain ecological processes in the long term. If you isolate Corcovado (by logging nearby forests), it will be dead in 50-100 years.

Corcovado is a biological jewel right now – it has all the same species that the Spanish found when they came here 600 years ago. But it will be lost if they don’t think of the connection to other areas, and protect Piedras Blancas National Park, and the Amistad National Park, and have them connected by way of biological corridors. That is where they are proposing these cuts.

The government talks about conservation, protected areas, how “green” we are, and that it will draw tourists. You hear the Environment Minister spreading all the propaganda abroad, and the conservation areas are collapsing. I was just in an area of Corcovado and the park guard tells me, “I’ve been here alone for two weeks, attending the hundreds of tourists who arrive every day.” And the protection?

If they fire those 50 park guards – who were hired with external funds that run out this year – the problem of hunting is going to return, we are going to lose species like the white-lipped peccary, and maybe even the jaguar.

Do you trust that the current administration will find the funds for to pay those guards, or are you concerned it’s not going to happen?

I’m concerned, and not just about Corcovado. The point is our protected areas are not receiving what they need to conserve their resources. People see the protected areas as an expense, and it’s not an expense, it’s an investment. What I’ve heard (Environment Minister Roberto) Dobles talk about is investing in infrastructure, having more trails, more buildings to receive tourists, and that’s all right. But under it all, we have to conserve the resources, and that is having more park guards, more people doing education. Because if there’s no resources, there’s no tourists, and they don’t understand that.

The way we are using the protected areas and natural resources is like milking a cow without feeding it. Sooner or later, it’s going to collapse. That is the concern that I, and many others who work in this, have.