Like thousands of expats before her, María Fejervary first came to Costa Rica on vacation. She came with her kids and another family. They spent some time on the beach. They enjoyed the sunny weather. They ate the food and wandered around, like any other tourist.

But Fejervary also spotted prostitutes. On the Central Pacific coast, Fejervary was appalled to see sex workers standing in the streets, in full view. She noticed how young many of them seemed. While adult prostitution is legal in Costa Rica, Fejervary guessed that many were actually underage, coerced into the trade by abusive criminals.

“We were looking for a fun place to vacation,” she told me recently. “We had no idea about any sex tourism here.”

When Fejervary returned to California, the images stuck with her. She knew a little about sex slavery and human trafficking, but now she stocked up on books, articles, official reports. She read everything she could get her hands on, and she started going to conferences. Fejervary wanted to help the victims in a meaningful way.

“When I went back to the States, I felt very called to come and do something,” she said. “Nobody’s really doing anything to fight it. There’s so much change that needs to happen in this country. It’s not about pointing fingers, it’s about changing things.”

Slowly, Fejervary formulated a mission: She would return to Costa Rica. She would build a rehabilitation center for young survivors of sex slavery. She would create an official nongovernmental organization, certified by the government-run Child Welfare Office (PANI). She would house, feed, educate and provide therapy for as many kids as possible.

Fejervary was no expert in human trafficking. She was not yet fluent in Spanish, despite having lived a short time in Mexico, and she doesn’t hold a college degree. She knew little about Costa Rican bureaucracy. Fejervary had spent most of her adult life running a daycare center and volunteering at homeless shelters. What did she know about founding a facility in another country?

Yet today, Fejervary is founder and president of Salvando Corazones (“Saving Hearts”). After an uphill battle that has lasted nearly half a decade, she has met every one of her goals. And if she can steer the organization steadily, the best is yet to come.

When I met with Fejervary, it was Costa Rica’s Independence Day, and the town of Tilarán was frenetic with activity. Fejervary had brought her colleagues and young wards to see the parades, and Tilarán, near Lake Arenal in north-central Costa Rica, was flooded with marching bands. The occasion was a fitting one for her outing: Costa Rica’s Día de la Independencia focuses a lot of attention on children. On the holiday’s eve, kids pour into parks and avenues with homemade lamps, or faroles, for the Lantern Parade, and the next morning young musicians play instruments and whirl batons.

“Aren’t they cute?” said Fejervary as a garrison of preteen brass players marched past. She looked happy and relaxed, not the fiery activist I had expected. Then she proposed to sit down at a local soda and chat. We broke away from the group, found a table, and ordered a couple of Coca-Colas.

“There are very few women out there who choose prostitution,” began Fejervary. “If somebody comes into [a brothel] and he knows the doorman, then nobody cares what happens in there. These [customers] need to go to jail. If we don’t hold people accountable, they’re not going to change their ways. We have to teach our children, at the kindergarten level, how to treat women. We have to create a society where [exploitation] is not okay.”

Fejervary is a straight talker. At 54 years old, she has a rugged smile and moves slowly, owing to many painful surgeries, including a recent operation on her back. In conversation, she is unpretentious and seems to hold nothing back. She has strong opinions about certain Costa Rican ministries, about the justice system, about well-known individuals she has met, and she expresses these opinions freely. Only one thing seems to matter to her: the recovery of the girls in her care.

“Why are you interested in this?” she asked me abruptly.

It was a good question. I explained my longtime interest in the issue of human trafficking, especially sex slavery. Compared to war or gang violence, the subject earns only a fraction of the media attention. The problem is pandemic and has ruined innumerable lives, yet unlike other social problems, people don’t like to talk about sex slavery. The subject seems too intimate, too painful and horrifying, to debate openly. Polite society will gab about drug addiction and serial killers all day long, but the thought of forcing a 12-year-old to have sex for money is too awful to contemplate.

On a more personal level, I told Fejervary that I had been solicited by scores of sex workers around the world, almost always in the street. All of them were adults, as far as I could tell. But it is difficult for a casual observer to distinguish consensual sex workers from women forced into the trade. I find this particularly unsettling, because millions of johns are exactly like me: normal-looking male professionals from a developed country. My interactions have always been brief – I would never hire a sex worker – but I have always wondered what happens to these people. (I say people, rather than women, because many of them were men or transgendered.) For sex workers lucky enough to escape the racket, how do they acclimate to normal life?

Satisfied with my response, Fejervary said, “Let’s go visit the home.” And we headed for our cars.

Initially, Fejervary had to decide where to start her program – that is, which country. While it was Costa Rica that had motivated her to take action, she considered a variety of possible nations.

“I had two prerequisites,” recalled Fejervary. “I had to like the weather, and I had to be able to learn the language. So that ruled out Asia.” She laughed. (She now speaks Spanish very well.)

Fejervary had visited Costa Rica on vacation more than once, and she finally whittled down her options and decided that Costa Rica was the most fitting base of operations. Fejervary founded Salvando Corazones as a nonprofit in 2010, but that was only the beginning of a difficult slog. Costa Rica already had a similar recovery program called the Rahab Foundation, which had earned praise for helping former sex workers. But Rahab works primarily with adults, and clients do not live on the premises. Fejervary wanted to improve upon its model: work entirely with children, and give them shelter as well.

To begin her search, Fejervary visited the Lake Arenal area with vague plans to obtain a property. She wanted to base her facility in a rural setting, far from sex trafficking hubs like San José and the province of Puntarenas. She had concerns that children might try to seek out former caretakers, no matter how abusive, because the kids yearned for familiarity. Many of the children would inevitably have substance abuse problems, and she had to curb access to drug dealers.

I asked her how she picked this place in particular.

“It picked me,” said Fejervary with a knowing chuckle.

During her visit, she said, Fejervary decided to sit down outside and take a breather. As she did so, a random man approached her and asked whether she was looking for real estate. The man wasn’t a licensed agent, but he guided her around the region, suggesting different sellers and properties. When she found the building that would one day become Salvando Corazones, she was awestruck: The large structure stood on a grassy bluff overlooking Lake Arenal. The surrounded lot had plenty of room for a garden and some livestock.

“I stood there and thought: ‘This is it,’” remembered Fejervary.

The building had some problems: It was new but also unfinished. The former owner had foreclosed, which meant Fejervary would have to spearhead final construction of the interior. Meanwhile, there was a family of squatters living inside – as well as their two cows.

Fejervary is no stranger to difficult, hands-on tasks: A native of Palo Alto, California, she has encountered plenty of challenges during her time working in homeless shelters, as well as running a daycare for 28 years. Fejervary is open about her own history of sexual abuse – she says that her teachers took advantage of her when she was young – and she uses this experience to work with vulnerable people.

“I tell the kids, ‘You can heal from it, and it doesn’t have to define you,’” said Fejervary. “‘But it is a part of you.’”

Fejervary has four adult children, two biological and two adopted. When she said that she had adopted two of her children from Russia, I was startled. Russian orphanages are perhaps the most disreputable in the world, where poor facilities, brutal caretakers, and rampant abuse are routinely reported. When she arrived in Russia to finalize the adoption process, she found herself counting $100 bills in a secluded room in front of dubious men.

“I thought to myself, ‘I’m involved in human trafficking,’” she recalled.

In short, Fejervary had faced tough personalities and tangled bureaucracy many times before, and she was determined to succeed. She managed to have her organization certified through PANI, enabling her to legally care for young victims of sex slavery. The certification was specific: Fejervary can only receive children and teenagers assigned to her by PANI. All of the children are female, and none of them can be pregnant. If a girl is discovered to be pregnant, Salvando Corazones must forfeit her to PANI.

During my visit, Fejervary said hello to several locals in Tilarán, exchanging waves and smiles. I asked her how she had adapted to living there, whether she had made any friends.

“They all know me,” she said grudgingly.

On top of all the other challenges, Fejervary claimed the community was suspicious of her intentions. She said they called her a child molester behind her back. In the year since the Corazones facility opened, she has had to fight the tide of gossip. Only recently has she sensed a change for the better.

The Corazones facility is secluded and hard to find, which is a good thing. But I wondered whether a relatively nearby town like Tilarán might also have its share of sex workers.

Fejervary shrugged. “I’m sure it does,” she said. “But it’s everywhere.”

“Everywhere” is no exaggeration: In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigations estimates that 293,000 minors are currently “at risk of becoming victims of commercial sexual exploitation.” On the international stage, an estimated two million children are exploited each year in the global commercial sex trade, according to activist group Equality Now. There are well-known hotspots, like Bangkok, Thailand, and Goa, India, but the geography of underage sex trafficking is borderless.

Costa Rica is one of those hotspots. For sex tourists, the nation is a favored destination, where transport and trysts are easy to arrange, and many forms of prostitution are legal. For watchdogs, the nation is notorious for its sexual exploitation. In its 2014 report on human trafficking, the U.S. State Department identified Costa Rica as a “Tier 2” Watch List nation. “The Government of Costa Rica does not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking,” noted the report. “However, it is making significant efforts to do so. In 2013, authorities convicted an increased number of trafficking offenders compared to the previous year and created a dedicated prosecutorial unit for human trafficking and smuggling.”

“I don’t trust statistics,” said Fejervary several times during my visit. She has a point. Sex crimes and human trafficking are both routinely underreported, no matter where they take place, and it is impossible to get a precise picture of the situation in Costa Rica. But the problem is glaring: Just this past week, the newspaper Diario Extra reported that police raided a suspected prostitution ring in San José, arresting six suspects. Police claimed to have rescued 70 alleged “sex slaves” from Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic.

Meanwhile, the sex trade in this country is infamous around the world. In 2007, the writer Sean Flynn wrote a vivid account of Costa Rica’s sex industry for GQ. Little has changed since Flynn’s story; his unflinching descriptions could as easily be written today. Flynn was writing about the legal sex trade for an upscale men’s magazine, but his conclusion was damning: After describing airport posters that warn against child prostitution, Flynn writes, “Welcome to Costa Rica, where it is illegal to rape children. Where it is necessary, in fact, to remind every single tourist entering the country that it is wrong to rape children.”

When discussing the sex trade and sexual exploitation, the distinction is important: While many critics passionately object to any kind of prostitution, prostitution by adults is legal in Costa Rica. Pimping, child prostitution, rape, sexual slavery, or foreigners smuggled across the border for the express purpose of selling their bodies are illegal. In theory, these crimes are a separate issue from the legal adult sex trade.

In practice, it’s not so simple. Prostitution is legal and regulated in all kinds of unexpected places, like Switzerland and Turkey. Yet when the industry is lucrative, the GDP is low, and laws are haphazardly enforced, a thriving legal sex trade in a country like Costa Rica arguably opens the door to illegal activity, including the sexual abuse of children. Costa Rica already hosts a steady stream of sex tourists, and many of them are predatory. Self-made pimps can find children, imprison them, and force them to service clients. The underground industry wreaks unspeakable damage on minors, and the nation is almost completely unprepared to rehabilitate the victims.

As the U.S. State Department’s report put it: “Victim services remained inadequate. … Government capacity to proactively identify and assist victims, particularly outside of the capital, remained weak.”

For full rehabilitation, Fejervary says a child needs at least two years of in-house care and intensive therapy. Survivors of Costa Rica’s sex trade likely number in the thousands. Since the facility started operating about a year ago, Salvando Corazones has cared for a total of 18 children. The oldest just turned 15.

Each morning at Salvando Corazones, the girls wake up in bunks, make their beds, and get dressed. From 6:50 to 7:15 a.m., they eat breakfast together in the open-plan living room, where the windows are broad and offer a breathtaking view of the valley and lake. They start class at 7:30 a.m. Lunch lasts from noon to 12:30. They have two 15-minute snack breaks. From 4:30 to 5:30 p.m., they get together for group therapy.

“Every hour is regimented,” said Fejervary as she guided me through the house. “Their home lives usually didn’t have any structure. They’re looking for structure.”

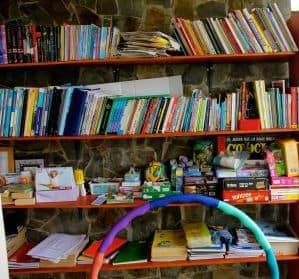

The rigid curriculum is based on years of group-home research in the U.S., but Fejervary and her staff have worked hard to embellish that rubric: The facility has a library with several hundred books, a Foosball table, a table tennis set, and board games. Nearly every bed and couch has its own stuffed animal, which the kids constantly pick up and embrace. The girls earn points for good behavior, but they can also lose privileges (mostly TV) for bad behavior.

What’s an example of bad behavior?

“Using bad words,” said Fejervary. But even in that case, the “bad” vocabulary is established as a group. The girls collectively decide what language is offensive to them. This is particularly significant in Spanish, where “puta” (“whore”) is considered one of the most vulgar insults, and many other slurs are disparaging of sexuality and women in particular.

Fejervary led me outside, where the hill sloped downward, toward a wooded defile, where an unseen creek flowed past the property. The shell of a building stood next door, its interior half-finished and full of building materials. Fejervary said that this building would eventually serve as a schoolhouse, but Salvando Corazones still required as much as $20,000 to finish construction.

“I don’t understand why it’s so hard to get finances,” said Fejervary.

Indeed, the facility’s operating costs amount to $31,000 per month, including food, utilities, wages for the full-time psychologist and teacher, and innumerable other expenses. Fejervary says that PANI is supposed to provide financial support, but so far the institution has only sent her kids. She has gotten this far thanks in large part to donations from a variety of sources (donations can be made through the nonprofit organization’s website).

If Fejervary can secure the funds she needs and Salvando Corazones becomes stable and sustainable, she wants to create an offshoot facility for pregnant girls, and then a third facility for boys, who are among the least-reported victims of sexual abuse. But for now they will have to wait until the schoolhouse is finished, among many smaller tasks.

We hiked down the hill, toward a coop with several chickens. The birds provide fresh eggs, and the girls use the surrounding gardens to cultivate carrots, onions, cucumber, squash, and herbs. Many of the young residents encounter a completely new diet when they arrive: Because vegetables are expensive, they often subsisted exclusively on rice and beans until they entered the PANI system. The Salvando Corazones staff ensures that they eat well-rounded meals, particularly veggies.

Back at the house, Fejervary pointed out the many murals that decorated the walls. Nearly every surface has its own colorful painting, such as rainbows and animals. In the stairwell, silhouettes of girls blowing dandelion seeds adorn the surfaces; this nook was called “the wishing wall.”

A noticeable omission is the heavy religious symbolism present in some rehabilitation facilities. There are no giant crucifixes on the walls, no inspirational Christian posters, nor excess of Bibles lying around the furniture. Fejervary herself grew up in a nonreligious household, and it was only when her young son, many years ago, took an interest in the local Presbyterian church that Fejervary attended a service. Now her son is pursuing a Ph.D. in Old Testament studies.

“I’m in the middle,” said Fejervary. “I like church and I like prayer, but I don’t need to call myself a Christian or anything else. I don’t need a title for that.”

As bucolic as the residence is, life at Salvando Corazones is rife with challenges. Girls have attempted to run away. Self-harm is a constant concern. Residents often have to learn basic domestic skills, like regular bathing, tidying up, or using toiletries. Breakdowns are common. During my visit, one of the girls burst into tears and sobbed for nearly an hour. At such moments, the girls are encouraged to visit Lorna Bastos, the in-house psychologist, in her private office. Because of their protracted trauma, anything could trigger a panic attack or emotional outburst, and the staff has to be prepared at any moment. Bastos provides one-on-one counseling. Such constant emotional problems might be wearying, but Bastos maintains a good attitude.

“Work problems I can leave at work,” said Bastos. “I’m thankful that God gave me the ability to separate personal problems from work problems or the problems of others. Many years ago, when I was a student, a psychologist professor told me that a person’s brain should be a like a stereo that can play several CDs. Every time I work, I put in the work CD, and when I leave, I take it out and put in my personal life CD, so that you don’t mix these CDs in your mind.”

“Would you like to talk with them?” Fejervary finally asked.

Although the girls themselves were the most important part of Salvando Corazones, I was shy about actually speaking with them. For obvious reasons, I couldn’t name them or photograph their faces, but I was surprised that Fejervary had invited me to the residence at all. Having grown up in a household where patient privacy issues were a big deal – my mother is a psychologist – I am fanatical about that issue, and I knew that the nearby La Fortuna Orphanage dissuades journalists from even contacting residents, much less visiting.

But I was happy to talk with two of the residents, whom I will call Zania and Alegría. Zania was bookish and bespectacled, and she said her favorite subject was math. She had lived at Salvando Corazones for 14 months, where she loved to study English, arithmetic and cake decorating.

“I like yoga,” she said, nodding. “I’m getting more flexible.”

Zania was particularly fond of the equine therapy program. When a local organization, Vínculo con Caballo, contacted Salvando Corazones and offered free therapy sessions with their horses, Fejervary was skeptical. “I thought, ‘Girls have fun with horses, that’ll be fun to do.’ I had no concept of what it was. And I certainly did not believe that it was possible to get the kind of results we’re getting from it.” During the group’s first visit, the children were blindfolded and put in the same space as the horses, and each horse then gravitated toward one of the girls. Then they mounted the saddles and were led through an obstacle course.

“It’s really fun,” said Zania. “The horse chooses me, and I choose him. I was afraid at first, but now I’m not.”

Alegría had spent seven months at Salvando Corazones, where she also loved math and reading. “I get to think,” she said. Before, when she looked out the window, she saw only ugly things. “Lots of problems, pollution, injustice. Now I see the lake, the volcano, the light, lots of trees, nature.”

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about Zania and Alegría was how normal they seemed. Spotted on a street or in a schoolyard, they would strike me as happy, giggly teenagers, perfectly well-adjusted, as innocent and fun-loving as neighborhood Girl Scouts. It is a testament to how much Salvando Corazones has accomplished: Many residents arrived with second-grade educations, and within one year they are testing into high-school level classes. Fejervary suggests that Salvando Corazones’ instruction is better than in most public schools.

What does Alegría want to be when she grows up?

“I wanted to be a gynecologist,” she said. “But first I want to be a schoolteacher, then earn a master’s in math, then become a lawyer, then an agricultural engineer…” She paused and smiled brightly. “Because I want to do everything.”

•

Whatever happens to Salvando Corazones, whatever challenges lie ahead, Fejervary looked as embedded as she could be. She had given up a satisfying job in a place that she loved. Her children are spread out now, and she could just as easily spend her time visiting them. But Fejervary has work to do, and if her budget will allow her, the organization will expand, providing some of the most desperately needed resources in the country right now.

“The kids always ask me, ‘Would you die for us?’” said Fejervary. “And I say, ‘Absolutely.’ Then they ask, ‘How come my mother didn’t love me the way you love me?’ I say, ‘She wasn’t capable. But you deserve it. You just have to love yourself enough to accept it.’”