NUEVA GERMANIA, Paraguay – To open the museum, señora Kück needs a hammer. She has lost the key, and the neighbor who should have a spare isn’t home today. But with a little olive oil and a few good knocks with the hammer, the lock springs open easily. She has done this more than once, Kück explains with a smile.

Inside the dusty building is a display of a few old pictures and artifacts of the German colonists who came here in 1886 to start an “Aryan colony” far away from the mainland of Europe, which they believed had been overrun by Jews. It’s not much of a museum, and Kück, who doesn’t look German, doesn’t know much about her ancestors, either.

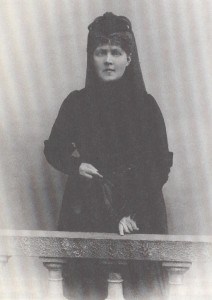

The most important part of the museum is the portrait pictures of the two founders of the colony of Nueva Germania: Bernhard Förster and Elisabeth Nietzsche, the latter being the sister of the famous philosopher. They came to the South American country of Paraguay with the dream of starting a “utopia,” but working in the humid jungle turned out to be much harder than expected. The potatoes they planted rotted away in the soil, and disease abounded. A type of sand fly caused infections that made life hard for the colonists. Although the infections weren’t deadly, the colonists didn’t know how to handle them, and they refused to ask locals for help.

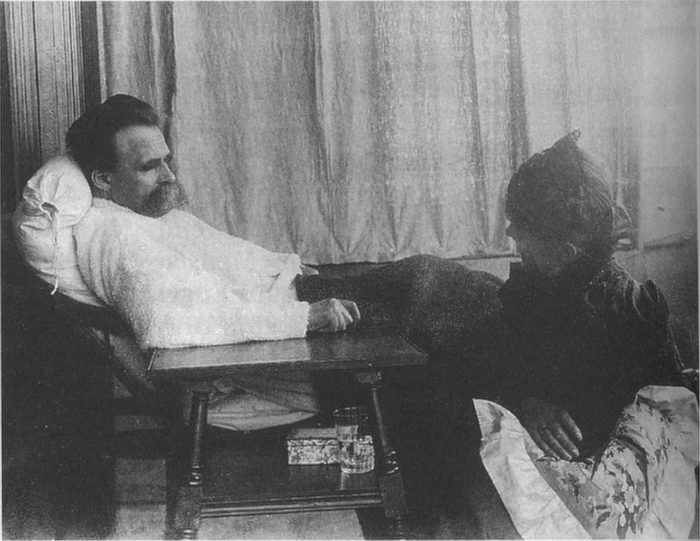

Förster committed suicide in 1889 in San Bernardino, close to the capital of Asunción, when after a few years of sweating in his Paraguayan colony he lost all hope. His wife, Elisabeth Nietzsche, fled to Germany to pester her crazy brother with her racist theories – going as far as making changes to Friedrich Nietzsche’s manuscripts after his death and turning his theories into anti-Semitic ones, as described by Ben McIntyre in his book on the colony of Nueva Germania, “Forgotten Fatherland: The Search for Elisabeth Nietzsche.”

“If Förster wouldn’t have abandoned his fellow colonists that early, it would have looked completely different here,” 74-year-old Arthur Raus, one of the only inhabitants of the village who knows something about its past, tells The Tico Times. The story of the colonists, according to Raus, is pathetic: Many died from tropical diseases they weren’t used to, while others returned to Germany. Those who actually stayed, and whose family names are still found among citizens, were those who simply didn’t have the money to pay for a return trip to their heimat.

But in the story of Raus, which he tells while drinking a beer on the porch of his village supply store, is a very interesting and almost symbolic point: Only when the remaining colonists began to listen to the indigenous locals in Paraguay did they manage to survive. Once they learned how to plant manioc instead of German potatoes, and once they learned where to look for freshwater, they found themselves with food on their plates at the end of the day.

What resulted was a colony that slowly began to lose its ties with Germany, and the original ideal of Aryan superiority. Although Raus calls the indigenous people Schweinehunde – a bad German word roughly translated as “pigs” – and is of the opinion that they “breed like rabbits,” this doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the ideology Förster and Nietzsche brought with them. It’s more the kind of general racism you would find anywhere in Paraguay, when you talk to German ancestors or Mennonites about the indigenous population. (Many are of the opinion that indigenous locals are lazy and prone to alcoholism.)

“What was the man’s name again, who killed so many Jews?” asks Raus when we get ready to leave. “Hitler, yes, that’s it. Everyone had to die with him, isn’t it? Not only those poor Jews, but also his political opponents. What a man.”

It’s difficult to find someone in the colony who still has an interesting story to tell about the ancestors. A little bit out of town, 63-year-old Flora Haudenschild remembers that her grandmother used to be picky on marrying with the indigenous. She wanted to keep the German blood “clean.”

“But I have a Paraguayan husband myself,” she says with a smile, adding, “one who knows what hard work is.”

Even if they would have wanted to keep the German blood so-called “clean,” at a certain point the settlers would have had to marry their own nephews. It’s an issue that is a point of discussion in the many Mennonite colonies in Paraguay, too: how to keep the gene pool moving with sufficient variety to avoid birth defects or other disabilities.

Haudenschild says they learned most about the history of their village from outsiders – from a German pastor, for instance, who came to town 30 years ago and told them a lot, and afterwards, from researchers and journalists who came trying to find signs of the original colony. But when asked about the German discipline, which was one of the main ideas of the colony for Förster, Haudenschild smiles.

“Well yes, I guess you could say that. We are very disciplined.”

Anthropologist Jonatan Kurzwelly, who recently spent 12 months in the town researching the German identity of its citizens, believes no one would have ever known about the fascist ideology if it weren’t for all the outsiders coming to look for it.

“Some media have gone for the sensationalist approach,” he says via Skype, “taking a racist remark out of context to make it look like this is a town full of Nazis. But the truth is that when these people say something about a Jew or about Hitler, they simply don’t have a clue what it means. For them, the Second World War is something very vague and far away.”

Although their connection to Germany boils down to speaking the language and using the German flag for a local football team, many villagers have the idea that they are still very connected to their old heimat. When confronted with bureaucratic reality, however, it turns out otherwise. Raus and his family have been trying to get a permit to go to Germany, where their autistic daughter might receive better treatment than in Paraguay. But for now, it turns out they are not German enough to be granted residency.