This Sunday is Mother’s Day in the United States, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and various other countries (excluding Costa Rica, where it’s celebrated August 15).

But in some countries, there is more to celebrate than in others. On average, one woman in 30 is likely to die from pregnancy-related causes, and seven out of 10 women will lose a child in their lifetime.

Despite global improvements in children’s and maternal health, inequality between the world’s richest and poorest mothers and children is widening, according to this year’s mother index released by the international non-governmental organization Save the Children.

The index shows where mothers and children living in urban areas face the least and the greatest hardships regarding women’s and children’s health and economic well-being, among other aspects.

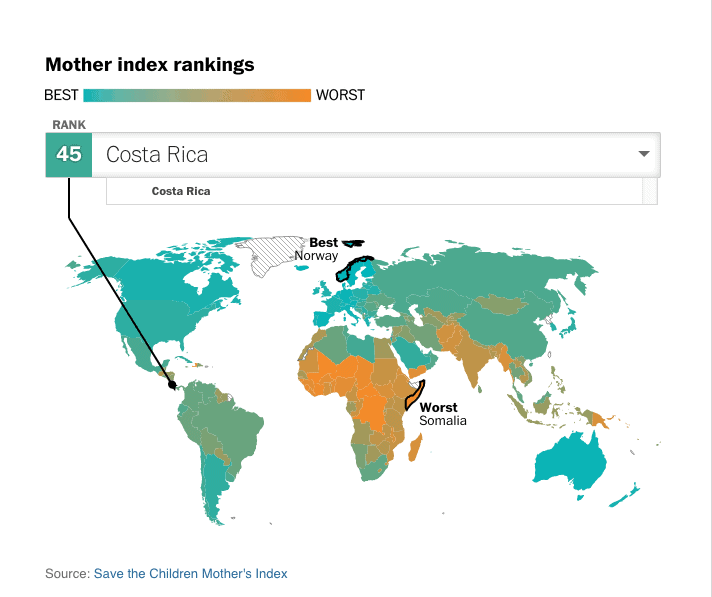

The world’s best countries for mothers to raise children are less of a surprise: Norway, Finland and Iceland. The United States, however, slipped from the 31st spot last year to the 33rd.

Costa Rica ranked 45 out of a 179 countries this year, slipping six spots from 39 last year. In Latin America, only Argentina (36) and Cuba (40) ranked higher.

Mexico was ranked 53, Panama 78, El Salvador 80, Nicaragua 102, Honduras, 109 and Guatemala 129.

You can click on individual countries in our map at this link to see how they rank.

Most countries at the bottom of the ranking are located in sub-Saharan Africa: Out of the 179 countries surveyed, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic perform worst. Nearly all of the bottom-ranked countries are affected by conflict.

Why education matters so much in the ranking

Due to the limited availability of comparable data, the index took into account factors that determine a woman’s as well as a child’s well being. The report’s authors focused on five factors in compiling the index: maternal health, children’s well being, economic wealth of a country, and the participation of women in national politics in order to be able to shape policies and debates.

Also factored into the index were the average years of formal schooling for children. In Costa Rica, that’s 13.9 years and in Guatemala it’s 10.6 years. The average for industrialized countries is 16 years of formal schooling.

“Numerous studies show a robust relationship between years of schooling and a number of important life outcomes, including income, health and civic participation,” Kathryn Bolles, the Children’s Director of Health and Nutrition for Save the Children, told The Washington Post.

Educated girls are also more likely to delay early marriage and motherhood which greatly improved the likelihood that they and their children will survive childbirth.

Growing inequality endangers mothers and their children worldwide

In more developed nations, other factors such as the ability of mothers to pursue careers or child benefits would be likely to play a role, as well.

“But as the majority of women in most developing countries do not have access to these benefits, it was not the single best indicator of economic status available,” said Bolles, explaining the decision to focus on child development indicators.

In the report, Save the Children urges that more resources need to be committed to tackling inequality in urban areas all over the globe.

“Increasingly, these preventable deaths are occurring in city slums, where overcrowding and poor sanitation exist alongside skyscrapers and shopping malls,” the authors conclude. In the lowest-ranked countries, children growing up in poverty are three to five times more likely to die than those with wealthy parents.

Among high-income capitals, Washington D.C. has the highest infant death risk. The finding that Washington D.C. performs worst in terms of infant deaths among 25 high-income global capital cities might surprise some. Whereas on average between 7 and 8 infants in Washington die out of 1,000 children, the number was as low as 2 in Prague, Oslo, Stockholm and Tokyo.

The authors argue that the high level of infant deaths in Washington is rooted in “pervasive poverty, young and uninformed mothers and poor prenatal care.” They also consider race to be a factor — with black mothers and families being over-proportionally affected.

In terms of politics, some developing countries outperform wealthier nations

Another finding of the index that could come unexpected is that Western nations are not as uniquely advanced in terms of women in politics as some might believe.

“Countries like Rwanda, Bolivia, and Cuba are doing a much better job of ensuring more equal representation of women in national parliament than many Western nations are, such as the United States, Ireland and Japan,” Bolles said.

In Costa Rica, 33.3 percent of legislative seats are held by women, compared to 19.5 percent in the U.S. (the world average is 22 percent, according to the report).

Why did political representation matter so much to the authors of the mother’s index?

“When women have a voice in politics, issues that are important to mothers and their children are more likely to surface on the national agenda and emerge as national politics,” Bolles said.

The organization’s overall conclusion follows her line of argumentation. Even in countries that face conflicts and wars, the situation of mothers and their children could be improved — if there were a political willingness to do so, according to the study.

“Some African countries, such as Eritrea, Ethiopia and Liberia have reduced their under-5 mortality rate by two-thirds or more since 1990,” Bolles said.

—

Noack writes about foreign affairs. He is an Arthur F. Burns Fellow at The Washington Post.

Gamio makes interactive graphics for The Washington Post.

Tico Times editor Jill Replogle contributed to this story.

© 2015, The Washington Post