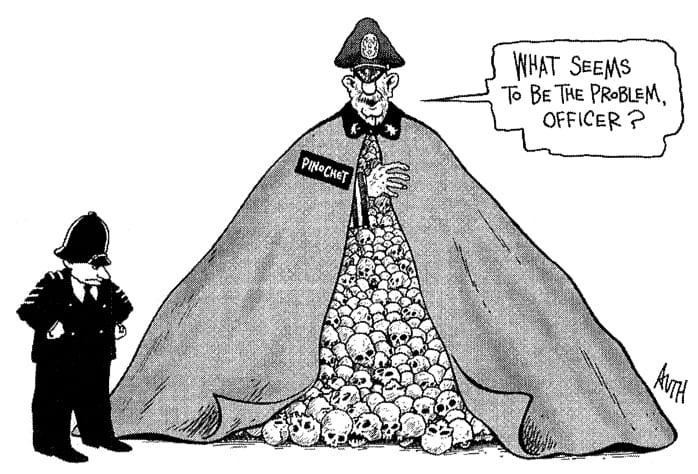

Also see our special report, “Pinochet’s Arrest Remembered,” published last October.

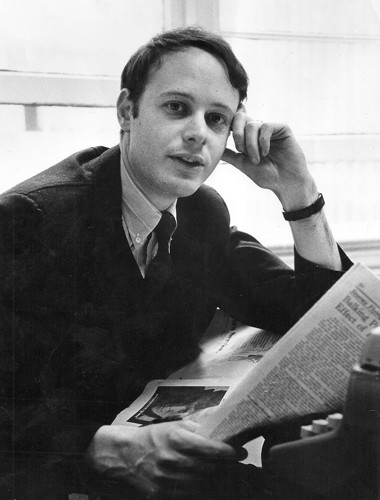

Last Wednesday in Santiago, Chile, Judge Jorge Zepeda’s office made public the results of a 14-year legal battle. The case stems from the 1973 murders of two U.S. citizens – Frank Teruggi and Charles Horman – in the days following a brutal coup d’état against the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. Teruggi, 24, and Horman, 31, had both gone to Chile to see and experience the new Chilean government. Allende died in the coup, thousands of Chileans were subsequently killed, and many more were imprisoned and tortured during the 17-year rule of dictator Augusto Pinochet.

The court ruling, issued on Jan. 9 but held for nearly three weeks until all of the parties were notified, sentences Pedro Espinoza, a former Chilean army colonel, to seven years in the killings of both men. Additionally, Rafael González, who worked for Chilean Air Force Intelligence as a “civilian counterintelligence agent,” was sentenced to two years of police supervision as an accomplice in the Horman murder only. Espinoza is currently serving multiple sentences for other human rights crimes as well.

The families of Teruggi and Horman also were awarded a cash settlement. Under Chilean law, a mandated appeal process will take place before final action is taken.

Janis Teruggi Page, Frank Teruggi’s sister, told The Tico Times: “Joyce Horman [Charles Horman’s widow] and I still have an appeals process to get through, which may last six more months. We also intend to increase our support for Universal Jurisdiction, because the arrest of Pinochet made investigations possible in Chile, and internationalized the crimes and took away sovereign immunity for torture.”

This month’s sentencing followed a ruling last June by Judge Zepeda that found that the two North Americans, in separate incidents, had been killed by Chilean military officials based on information provided to them by U.S. intelligence operatives in Chile. Judge Zepeda’s investigation, which began in 2000, asserted that the targeted killings were part of “a secret United States information-gathering operation carried out by the U.S. MILGROUP in Chile on the political activities of American citizens in the United States and in Chile.”

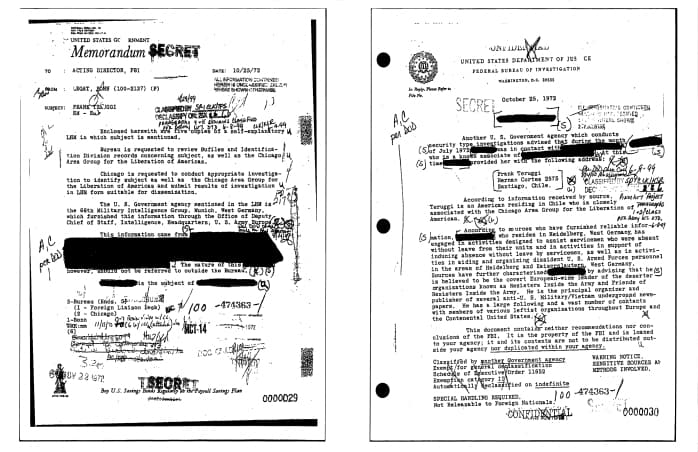

One piece of evidence, an FBI memo dated Oct. 25, 1972 – 11 months before Frank’s arrest following the coup – listed Teruggi’s street address in Santiago. If this document had been shared with Chilean security forces, it certainly would have allowed them to locate him quite easily for arrest.

A September 2000 U.S. Intelligence Community report affirmed that the CIA “actively supported the military Junta after the overthrow of Allende.” But, in spite of this admission, much of the specifics of the U.S. role remain obscured.

“After 14 years of investigation, the Chilean courts have provided new details on how and why Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi were targeted and executed by Pinochet’s forces,” said Peter Kornbluh, author of “The Pinochet File.” “But legal evidence and the verdict of history remain elusive on the furtive U.S. role in the aftermath of the military coup.”

Kornbluh is a senior analyst at the National Security Archive, an independent nongovernmental research institute and library located at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., that has been collecting and analyzing documents about the U.S. role in the Chilean coup since the mid-1980s. In June 2000, they released an electronic briefing book of documents relating to the deaths of Teruggi and Horman. These documents and others were part of the evidence reviewed by Judge Zepeda.

In 2011, Zepeda, a Chilean special investigative judge, indicted and attempted to extradite former U.S. Navy Capt. Ray Davis, who was head of the U.S. Military Group at the U.S. Embassy in Santiago at the time of the coup. Davis, it was later discovered, had left the United States in 2011 and was living secretly in Chile, where he died at the age of 88 in a nursing home in April 2013 – before he could be located by authorities. His death leaves many questions unanswered.

The 1982 film “Missing” portrays Ray Davis (called “Capt. Ray Tower” in the movie) and other U.S. Embassy officials as being much more involved in the coup and its aftermath than the U.S. public was aware. In an attempt to gain more understanding of what had happened to his son, Frank Teruggi Sr. joined a delegation that traveled to Chile from Feb. 16-23, 1974. The group, called the Chicago Commission of Inquiry into the Status of Human Rights in Chile, stated in its report (excerpted and printed in the New York Review of Books on May 30, 1974): “The Embassy of the United States seems to have made no serious efforts to protect the American citizens present in Chile during and after the military takeover.”

Janis Teruggi Page said that she and Joyce Horman now would like the U.S government to look into these killings more thoroughly.

“We are now asking the U.S. Navy, the State Department and the CIA to investigate on the basis of the information [in Judge Zepeda’s ruling] pointing to U.S. officials, especially Captain Ray Davis,” she told The Tico Times.

The importance of Judge Zepeda’s ruling, and the fact that it clearly indicts a U.S. official for having a role in these deaths, may help to move the investigations forward, but the full extent of involvement by the U.S. government in these events may never be known. After the sentences were announced this week, Frank Teruggi’s sister, Janis Teruggi Page, told journalist Pascale Bonnefoy in the New York Times, “Frank, a charitable and peace-loving young man, was the victim of a calculated crime by the Chilean military, but the question of U.S. complicity remains yet to be answered.”

Norman Stockwell is a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin, and serves as operations coordinator at WORT-FM Community Radio. His 1998 article on Madisonians who experienced the coup in Chile can be found here. His previous articles on Frank Teruggi have appeared at Progressive.org and in The Tico Times.