WASHINGTON, D. C. – Cristina Equizábal, a senior fellow at El Salvador’s National Foundation for Development (FUNDE), visited Costa Rica earlier this month – and was shocked to learn that local police had uncovered an enormous cache of M-16s, Uzis, AK-47s and other weapons in a suburb of San José.

Despite Costa Rica’s reputation as a relative haven of calm in one of the world’s most dangerous regions, the raid proved to her that generalized statistics about the safety of one country relative to another often can be deceiving.

“Some neighborhoods of San José and Limón have homicide rates of close to 60 per 100,000 – just as high as some places in the Northern Triangle,” Equizábal said in reference to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, three of the most violent nations on Earth.

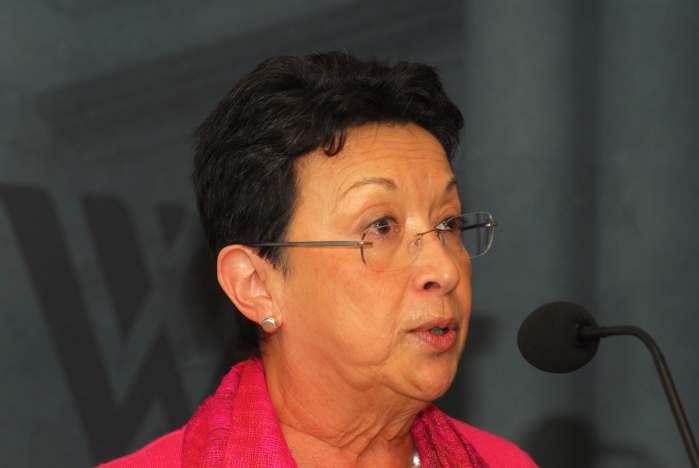

Equizábal was one of nine speakers who participated in a Dec. 11 conference on Central America’s security challenges. The first half of last Thursday’s event – sponsored by the Washington-based Wilson Center – focused on the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), a U.S. taxpayer-funded program that since 2008 has spent $642 million to combat crime, gang violence and drug trafficking throughout the region.

“One thing CARSI is missing is knowledge,” said Equizabál, who before joining FUNDE in San Salvador directed the Latin American & Caribbean Center at Miami’s Florida International University. “The situation on the ground is very variable. In El Salvador, for example, homicides are concentrated in 14 of the country’s 262 municipalities – and there are 45 municipalities that have not had a single homicide in six years. You have to stay very close to the ground in order to tailor your response.”

Asked if CARSI is a success or a failure, Equizábal said the answer depends on the level of analysis.

“Individual projects have mostly been successful according to the criteria established, and the people implementing them in El Salvador are fairly satisfied.” But in order for such initiatives to really succeed, she said, “you need a stronger tax base, more transparency and increased accountability from all sectors of society.”

Related: Top U.S. diplomat defends Central America Regional Security Initiative

Guatemala, with 16 million inhabitants, is Central America’s most populous country and has received the biggest chunk of CARSI funds to date. But how much the program has actually helped Guatemala is a big question mark, said Nicholas Phillips, author of the Wilson Center study, “CARSI in Guatemala: Progress, Failure and Uncertainty.”

He said U.S. officials have conducted no evaluation of a CARSI-funded heroin poppy eradication program, and there’s no evidence these programs have actually affected the volume of cultivation. In addition, programs to establish model police precincts have had some success in the specific areas where they were established – but they haven’t been expanded because the government isn’t committed to the program.

“The most common crime in Guatemala is everyday robbery and theft. Sadly, violence against women is also very prevalent, and 70 percent of the time people don’t even bother reporting crimes,” said Phillips, a Wilson Center consultant since 2013. “Most Guatemalans don’t have a lot of faith in their public institutions. The police are not well-trained, and they don’t have a tight relationship with folks on the street.”

He added: “In a recent survey of 10,000 people in the capital, 90 percent said they had not been a direct victim of crime in the last eight months, but they also said it was an unsafe place to be. Guatemalans are afraid – they don’t go out at night and they don’t trust strangers.”

On the other hand, said Phillips, “public prosecutors have gotten a lot better in the last few years, especially under the leadership of [former attorney general] Claudia Paz y Paz. He said the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has done a “solid job” bolstering the Guatemalan court system by installing one-way, bulletproof windows so that witness can testify anonymously and safely against “bad guys.”

See also: Experts debate approaches to stemming Central America gang violence

In addition, the State Department’s International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau (INL) has provided equipment to Guatemala’s PANDA anti-gang unit, helping it collect wiretaps and videos and working with prosecutors to build strong cases against gang members.

“INL helps vet these guys. Every six months they have to take a lie detector test. Everyone I interviewed said they’re doing a good job,” he said, noting that INL is also actively promoting the U.S.-developed Drug Abuse Resistance Education program – even though evaluations of DARE in the United States show little or no impact.

“We’ve got to better evaluate what we’re doing with our CARSI money,” said Phillips. “Frankly, it’s not enough to say we trained 1,000 officers or we gave them 100 new laptops. Those are outputs. We want outcomes.”

Much the same is true in Honduras – the world’s most violent country – where homicide rate has begun to fall after reaching 90.4 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2012.

“While it’s still the highest in the world, there’s a clear trend toward [rates] going down. That’s because Honduras is addressing high-level organized crime, but they have farther to go in that respect,” said Aaron Korthuis, a Yale Law School student who spent two years working in Honduras with two nonprofit groups working to reform the country’s police and justice sectors.

“Only 4 percent of homicides in Honduras reach a conviction, so there’s very little deterrence effect. That’s why you continue to see high impunity rates,” Korthuis said. “Change is happening, but slowly and often faltering and ridden by corruption.”

Steven Dudley, co-director at Insight Crime and a former Wilson Center fellow, said a big part of the problem is that projects like CARSI are destined for nations run by wealthy elites who evade taxes and deplete their country’s security and justice systems.

“Stories abound in places like Honduras, where public ministries are lending printers to the police, where there’s one car for every 50 cops,” he said, suggesting that Central American presidents are being unrealistic in their demands that the United States bankroll their proposed Alliance for Prosperity plan. That program was unveiled during last month’s visit to Washington by the leaders of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

“We need to put this into perspective. With Plan Colombia, for example, $8 was spent by Colombians for every dollar spent by the United States. In Mexico, it was $10,” Dudley told his audience. “These countries in Central America are spending much less, on average, for these programs, and they’re asking [Washington] for incredibly outsized sums in the amounts of $5 billion. There’s a complete disconnect between the reality on the ground and what they hope to get from the U.S. government.”

See also: For justice in Guatemala, ‘2 steps forward, 1 step back’