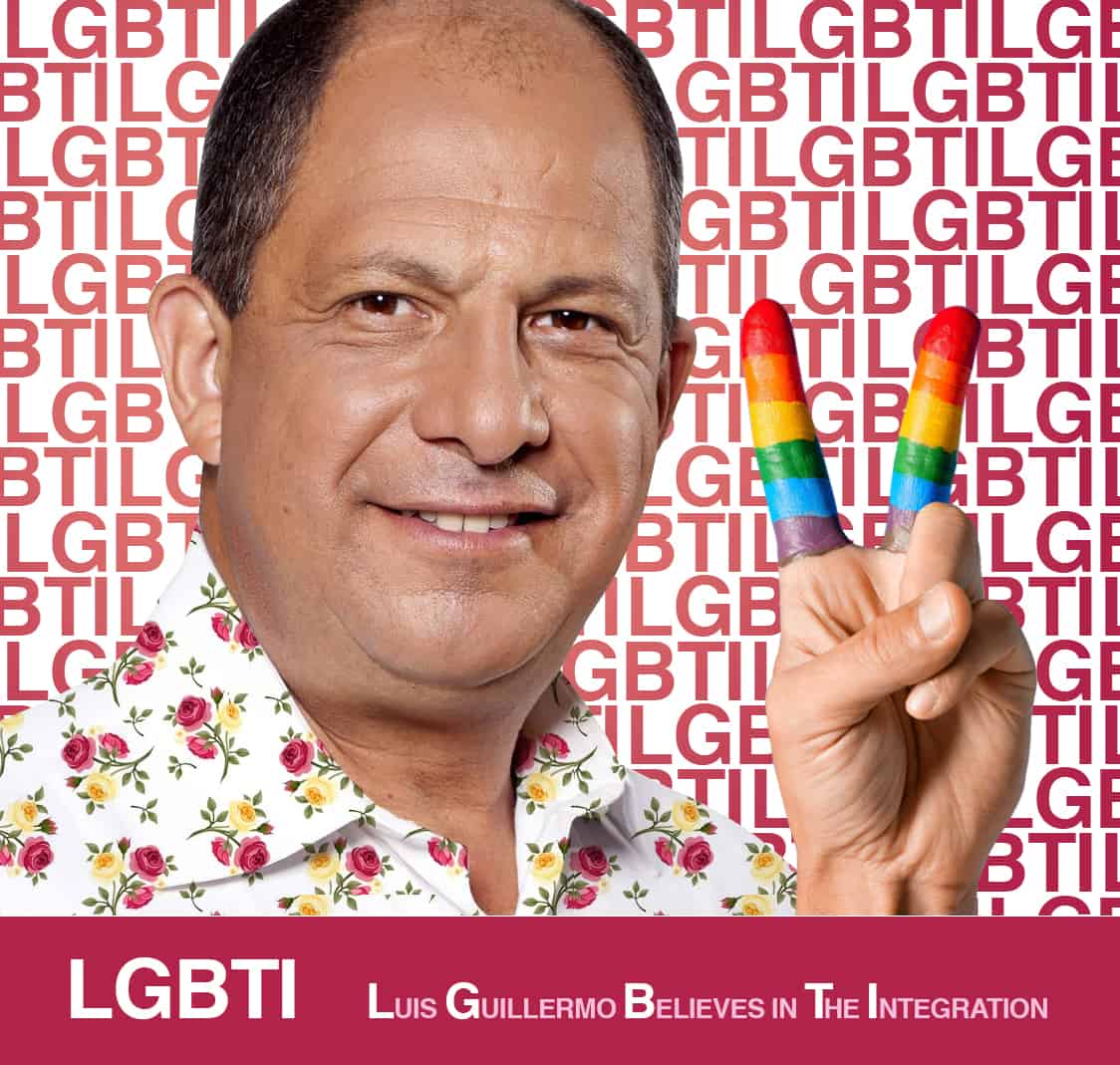

Luis Guillermo Solís has barely begun his presidency and already the LGBTI communities have much to celebrate. For one, Solís is the first president of Costa Rica who has familiarity with the gay nightlife of San José. Or at least he is the first president willing to publicly admit it.

In January on Costa Rica’s Channel 9 program “¿Como Está la Vara?”, TV personality and host Choché Romano asked Solís if he invited him to Bochinche or La Avispa (two of San Jose’s oldest gay bars) to celebrate his birthday, would Solís go? Then-candidate Solís revealed that he had been to gay bars before and would have no problem attending such an occasion. In the same interview he opined that gay domestic partnerships should be treated under the law the same as common-law marriages, granting partners all civil and inheritance rights enjoyed by any marriage or common-law marriage. Solís stated that homophobia and the violation of a gay person’s rights was incompatible with a democratic regime.

Incompatible too, one might argue, is a state religion. And the absence of a public prayer from the inaugural ceremony could be suggestive of Solís’ belief in separation of church and state, even as he personally evoked God in his inaugural address and took the oath of office with his hand on a Christian Bible. Such actions are consistent with his April 8 statement that, “A secular state isn’t a state without God, but rather a state that guarantees the religious freedom of all citizens.”

Extreme right homophobia is often rooted in misinterpretations of biblical scripture, and attempts to base public policy on religious texts far removed from their original context is a fool’s errand under the best of circumstances. Solís’ conception of a state that protects religious freedom for all is consistent with a state that protects the individual’s practice of any religion, or no religion, as one of many individual rights that the state should guarantee to everyone. Making all forms of discrimination illegal and guaranteeing equal access for all to state benefits and recognitions is one of the guiding principles of Solís’ governing vision, and in this case should mean significant legal advances for the LGBTI communities.

In the parade of newly appointed officials in attendance at the May 8 inauguration was the presence of Tourism Minister Wilhelm von Breymann and his gay partner of 19 years, Mauricio Alfaro, marching together in the inaugural procession. Largely lost on the many Costa Ricans in attendance, Breymann’s inclusion of his gay partner was later reported widely through social media and in the press.

The importance of Breymann’s participation is not that it is the first time a gay government minister has been in attendance at the inauguration – this no doubt has occurred on many occasions. Rather, this moment is different because it is the first time in history that a Cost Rican government minister has felt free to include a same-sex partner in such an official procession. On May 8, 2014, President Luis Guillermo Solís and his tourism minister have taken the symbolic first steps toward the dismantling of Costa Rica’s lesbian and gay closet.

Symbolism in politics is important, and the most effective presidents often use this power to change public opinion before they take steps to change public policy. On Dec. 31, 1963, Lyndon Johnson put the full symbolic clout of the U.S. presidency behind the cause of civil rights during his visit to the Forty Acres Club, a “whites only” club in Austin, Texas, when he arrived with Gerri Whittington, one of his African American secretaries as his “plus one.” She had asked him beforehand if he knew what he was doing, and Johnson replied, “I sure do. Half of them are going to think you’re my wife, and that’s just fine with me.”

Understanding well the power of symbolic politics, Johnson’s de facto integration of a “whites only” club surprised, shocked, and most importantly, demonstrated presidential leadership without waiting for Congress to act on civil rights. When asked the next day if blacks were now permitted to enter the club, the management responded, “Yes, the president of the United States integrated us on New Year’s Eve.”

While a symbolic gesture can never take the place of legal recognition and protection (Johnson’s symbolism was later followed by the passage and signing of the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act), it can help to change minds – even those long set against greater equality for all. The inclusion of Minister Breymann’s partner in the inauguration and the president’s easy admission of his own visits to gay bars with friends sends a message that Costa Rica under President Solís intends to be a part of the progressive pink Zeitgeist sweeping the world.

In recent years, gay marriage has become legal in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and in the state of Quintano Roo, Mexico, and in Mexico City, one of the world’s most populous cities. French Guiana, Ecuador and Colombia all recognize civil unions between same-sex partners. Missing from this growing list is any state in Central America, and Costa Rica is the place in the region where such legal recognitions would likely next occur.

As the region’s leader in democracy, an extension of the legal protection of the rights of lesbian and gay couples would be a natural next step. A poll conducted by the daily La Nación in January 2012 indicated that 55 percent of Cost Ricans supported the statement that “same-sex couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples.” The number increases to 60 percent among those aged 18-34. At the official level, the Costa Rican government has recognized gay marriages from other countries in its diplomatic relations, granting longer term and special visas to members of the diplomatic corps who bring same-sex spouses to Costa Rica.

Further, every survey of voters’ opinions on same-sex marriage in Latin America has shown that those most likely to support equal rights for same-sex relationships are younger, better educated city dwellers. With 80 percent of Costa Rica’s population living in the Central Valley, with 40 percent of the population under 25 years of age, and with the often touted “well educated” Tico workforce continuing to grow, support for same-sex equality can only rise in Costa Rica, suggesting that politicians of all stripes would do well to pay attention or risk sentencing their party to the dustbin of history.

Despite its appearance to many to be happening at the speed of light, social change never happens overnight, and Costa Rica has had a vibrant political gay movement for decades. Through the Herculean labors of gay activists like Marco Castillo, a lawyer and president of Movimiento Diversidad, and Francisco Madrigal, founder and director of internationally renowned Centro de Investigación y Promoción para América Central en Derechos Humanos (CIPAC), Costa Ricans now enjoy greater protection from sexual diversity-based discrimination than any of their Central American neighbors. CIPAC’s work has yielded presidential decrees setting up national days of recognition against homophobia in the last two National Liberation Party administrations. And this week, the Social Security System is considering a change that would allow gays and lesbians to insure their partners, and same-sex partners to be listed as emergency contacts, and it would guarantee hospital visitation rights to gay partners.

Solís’ new president of the Caja, María del Rocío Sáenz, using almost identical language to Solís’ January interview with Choché Romano, has already said that the proposal to extend insurance coverage to same-sex couples is tantamount to a human right.

Enormous progress has been made and will continue to advance in Costa Rica, and Solís’ strategy of a democratization of the state makes it clear he is willing to do whatever he can to advance the equal treatment of lesbians and gays, even if the legislature fails to act to pass a civil union bill.

In 1998, Nobel Laureate author Toni Morrison called U.S. President Bill Clinton the first “black” president of the United States based on Clinton’s empathy and affinity with the African American communities. It was a title of honor Clinton has long embraced. Although only in the first days of a four-year term, several indicators suggest that the administration of Luis Guillermo Solís will be the most progressive in the history of gay rights in Costa Rica. Could he be vying for the title of Costa Rica’s first “gay” president?

Gary L. Lehring is a professor of government at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. He is on sabbatical in Costa Rica.