Few of us will ever get an opportunity to visit Isla de Coco: this national treasure. This oasis in an ocean. This center for international biological research and sanctuary for fish, whales, turtles and huge manta rays. The island is 500 kilometers from Costa Rica’s mainland. There is no landing strip for planes and a boat trip is long and uncomfortable.

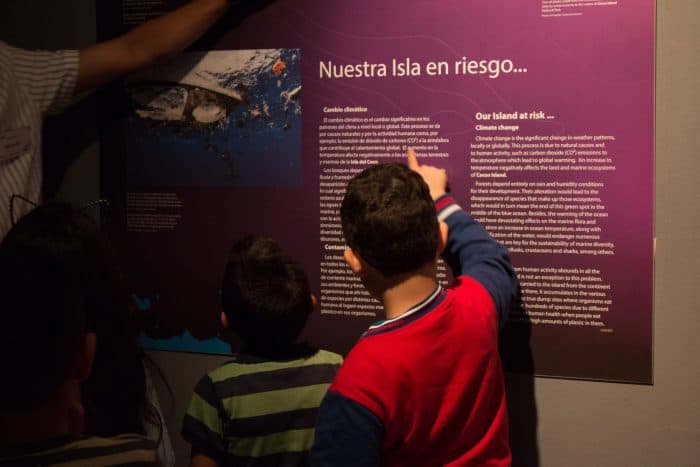

But a special exhibit at the national museum is almost as real.

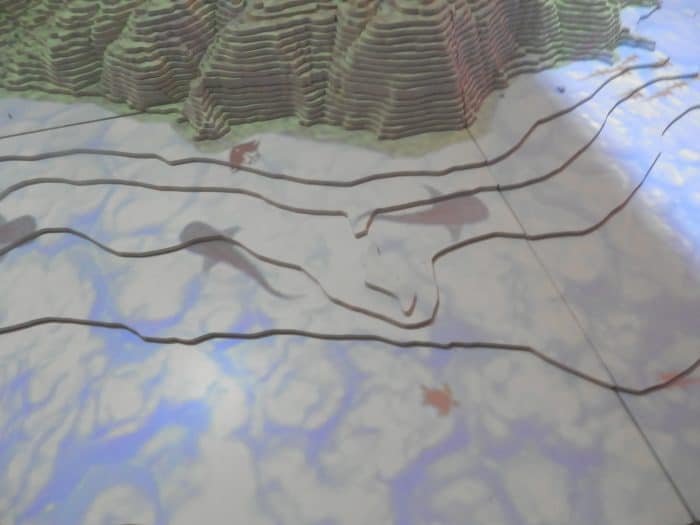

Using video mapping and other technological tools, we can experience a full day at the island, see rain clouds gathering overhead, and feel the mist of fog. We can watch as schools of hammerhead sharks congregate and disperse, turtles nip at corals, and gangs of giant rays stream by. We can even see what it’s like underwater on a wall-size screen as schools of fish numbering in the thousands pass by, followed by a whale shark taking up the entire screen and a tiger shark’s beady eyes look right at you.

Cushions on the floor and comfortable chairs are for those who want to spend time here. This special exhibit is on until August 19, 2018.

“We’re bringing the island to the people,” says Marco Díaz, a biologist connected with the project, which is the result of coordination between the University of Costa Rica’s Marine and Freshwater Research Center (CIMAR) and the National Museum. The exhibit shows research in sea science in an easy-to-understand way.

“It’s a laboratory with different climates and plant-life, ferns and mosses and a type of orchid that grows only on Coco Island,” Díaz added. Climate change and its effect on land and water is part of the research.

A gallery of photos of flora and fauna show the extent of life on the island. The island is an extinct volcano that stopped being active several million years ago, but the base of hardened lava is seen in some of the photos.

This year celebrates forty years since the island became a national park, but its recorded history goes back to 1526, when Spanish captain Joan Cabeças first landed on the island. In following centuries it was claimed by pirates, England, Spain, and the United States, but nobody really wanted it. It was too far away from the mainland, and its uneven topography and lack of a safe harbor made it worthless.

Costa Rica, however, saw the value of this parcel of land that lies closer to Colombia than its own shores, and acquired it in 1863 to use as a prison, among other things.

“This exhibit shows the public what a treasure we have,” says Díaz. “Coco Island has more diversity than any other spot on earth. Daily rain produces sweet water for rivers and pools, adding to the diversity of life. The water surrounding the island is protected by law, giving sea life a good chance to grow, feed and reproduce. The land surface is covered with trees, ferns and mosses and is home to sea and migrating birds. Wild pig and deer populations live here, brought by the English in an attempt at colonizing and, left to themselves, continue to grow.”

Because of the abundance of fish, illegal commercial fishing is a problem. Approximately 22,000 square kilometers surrounding the island are protected. The island has no accommodations for tourism but some tour companies offer tours, mostly for diving.

The museum is open Tuesdays to Saturday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and Sundays from 9 to 4:30. (closed Mondays) located on Calle 17 between Avenidas Central and 2. Tickets are ¢2,000 (about $4) for nationals and residents with a cédula. Foreign visitors $9, foreign students with ID, $4. Children under 12 are free. Also, nationals and residents over 65, and students with school IDs, enter free, and everyone can enter free on Sundays. Entrance is for the entire museum and the butterfly area.