PUERTO VIEJO DE SARAPIQUÍ, Heredia — The peccary stared me down, seemingly daring me to come closer, but I figured the last thing I needed all alone on a trail in the jungle was a fight with an angry pig.

So I kept my distance, snapping pictures, and the pig kept his. There were several in the herd, rooting in the fields alongside the trail, the air heavy with their musky smell. Not five minutes ago, I was snapping pictures of a mother spider monkey swinging in the trees with a baby on her back. This was starting to feel like “Animal Farm,” Costa Rica-style.

Later I saw peccary strolling the manicured grounds among researchers’ living quarters at La Selva Biological Station as casually as cats or dogs, and I realized they’re about as dangerous as Wilbur from “Charlotte’s Web” (unless, of course, you mess with them).

La Selva, a few minutes south of Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí and a couple of hours from San José, is one of the premier tropical research centers in the world. Located in lowland Caribbean rain forest north of Braulio Carrillo National Park, this private reserve is a marvel of conservation where the biodiversity needle is set to “Extreme.”

And just wait till you try the ziplining, the Tarzan swing and the whitewater rafting — oh, wait, they don’t offer any of those here. This is a place dedicated to research, not to giving tourists thrills. But visitors of all kinds are welcome, and you may find that stumbling on a wild boar is actually more thrilling than a canopy tour.

La Selva is one of three research stations operated by the Organization for Tropical Studies, a nonprofit consortium of more than 50 universities and other institutions, founded in 1963 to promote research and education in tropical biology and the sustainable use of tropical resources.

The organization offers graduate-level courses in ecology and natural resource management, with close to 10,000 students having taken its courses. Every year upwards of 300 scientists from all over the world work at its research stations, which also include the Palo Verde Biological Station and Las Cruces Biological Station.

I first heard of La Selva when I interviewed Donald Perry, who invented the jungle canopy zipline right here in 1979 to enable him to move among three huge trees where he was conducting research in the canopy, or what he calls the “main level” of the rain forest.

Imagine my surprise when I went to dinner at 6 o’clock on Thursday and saw none other than Don Perry, now 36 years older, sitting at a table with Carlos de la Rosa, director of La Selva.

Don introduced me to Carlos and said I was with The Tico Times, thus blowing my cover, as I was trying to avoid the special treatment often given to journalists in Costa Rica. But I’m glad he did, because Carlos ended up giving me the ultimate tour.

Perry is in Costa Rica to market his EcoTram, a self-guided cable car that moves through the canopy, one of which is already up and running at Hacienda Barú, near Dominical. But he was at La Selva to consult on how to dismantle some observation towers that a tree had knocked over.

“Canopy access is like the bottom of the ocean — you need a submarine to get down there,” Carlos said. “Here we have the towers. These are towers that come right out of the forest, up to 50 meters ….

“We had two towers that had a bridge in between them, and a tree knocked down one of them, and this one fell and brought the other one down. So Don is helping us with the expertise to disassemble it because it gets caught up in the trees. It’s like a stick game with giant towers.”

After a lively conversation over a forgettable dinner of arroz con pollo, I returned to my solitary $65 room, which had three bunk beds and a private bathroom. (I opted for the $65 option with one meal a day, declining the $95 option with three meals a day, and I decided that was a good call, as no two meals here are worth $30.)

Carlos told me that perhaps 30 percent of the visitors here are tourists, primarily birders, while 70 percent are researchers and students. La Selva does not strive to be a major tourist destination, so if you come here don’t be surprised if your accommodations are less than Hilton-esque.

My room was pretty basic, with no A/C or TV (not that I needed them) and no glass in the windows, just a screen. As I lay me down to sleep, a cold, windy downpour outside the screens chilled me, and I searched for first one blanket and then another. The rain continued through the night, often waking me with its pounding on the zinc roof, and I slept very little. But I enjoyed waking up from my nightmares, because at least I knew I had caught some sleep.

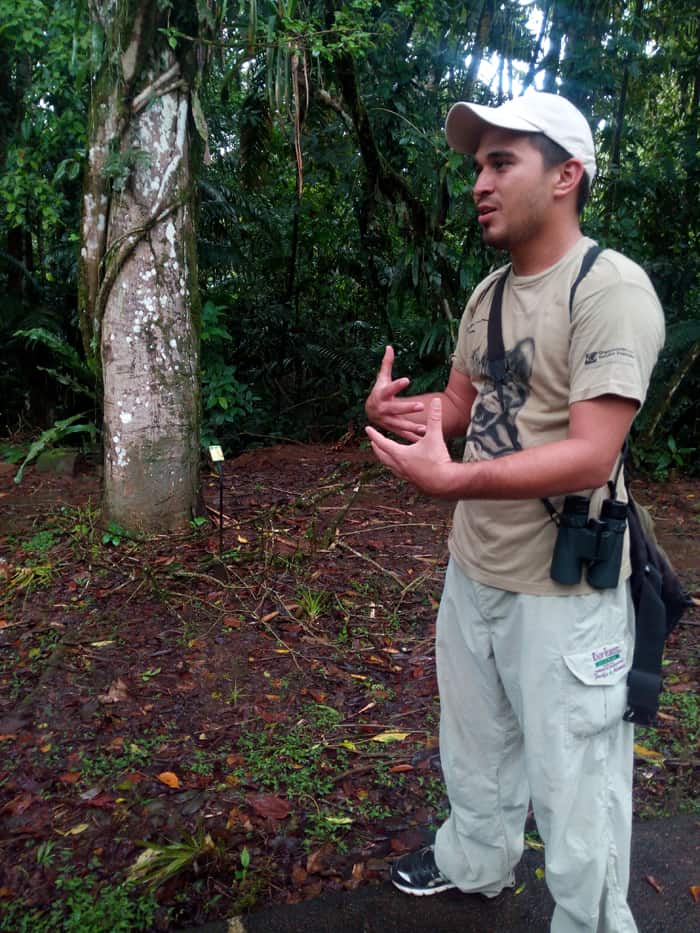

At 8 a.m. I joined a guided nature walk (included), where Tico naturalist guide Reimer Palma, 25, took me and four other Californians on a three-hour hike. La Selva has 61 km of trails, of which 16 km are paved with either cement sidewalks or cement tiles.

We saw poison dart frogs, more peccary, a huge bullet ant and multiple bird species: black-faced grosbeak, chestnut-sided warbler, crested guan, black-mandibled toucan, broad-billed motmot, stripe-throated hummingbird and ochre-bellied flycatcher. And we heard but failed to see the one bird on my bucket list, a great green macaw.

At one point a big branch crashed to the ground nearby, and Reimer said, “What we have over here, it’s known as T. rex.”

A woman in our group said, “Hey, I didn’t see that in the waiver.”

Midges among us

In the afternoon I went looking for Carlos de la Rosa, who graciously received me in his office and took me on a tour of the research facilities he oversees.

It was kind of like “Jurassic Park” lite — extraordinary laboratory facilities in the middle of a totally wild jungle, but without two-story-tall predators to devour innocent visitors.

Carlos, 60, who is from Venezuela but studied aquatic ecology at the University of Pittsburgh, is a specialist in midges — mosquito-like insects that don’t sting or even eat as adults.

“They live a few hours, at the most a day or two as adults, but their life cycle in the water is tremendously important — they are the food base,” Carlos said. “All the fish eat them, all the insects eat them.”

He called them the “white meat” of the food chain. Midges: It’s what’s for dinner.

He explained that they start as eggs, emerge as larvae, live for a few weeks or months and then pupate.

“Then when this pupa is ready to emerge from the water, it swims to the surface, opens up and out comes the adult — instantaneously. And the adults swarm and mate and lay eggs. Then they die and the cycle starts again.

“What I’ve been doing for over 30 years is collecting the skins they left behind.”

Strange hobby you have there, señor.

Carlos showed me a bag of the “soup” he collects from rivers, which he said contains tens of thousands of tiny midge skins. He picks them out of the soup and then separates them by species. And how can he tell the species apart? Because he’s one of the world’s leading experts, that’s how.

“I have 134 species that were completing the life cycle that day, and that’s extraordinary,” he said. “Nowhere else in the world will you find this. That level of species richness is unique to this area, to Costa Rica.”

He said there are perhaps 10,000 species of midges in the world, and 1,000 to 2,000 in Costa Rica. Yet only 60 species have been identified, he said, “so we got a long ways to go.”

He showed me a collection of midges mounted on slides. “We have a catalogue of 100,000 specimens,” he said. “This is one of the three largest collections in the world, and it’s the largest in the tropics.”

So all you people out there who are deathlessly interested in midges, you definitely want to stop by this place.

Lab in the jungle

Carlos showed me around the research facilities, which consist of laboratories full of microscopes and other sophisticated devices to do what I call “science and stuff.” He explained that researchers rent space here, telling him what equipment they need, how much space, how much time, three hots and a cot, and La Selva tallies up their needs and comes up with a fee.

“It’s like a hotel with a very large laboratory,” he said.

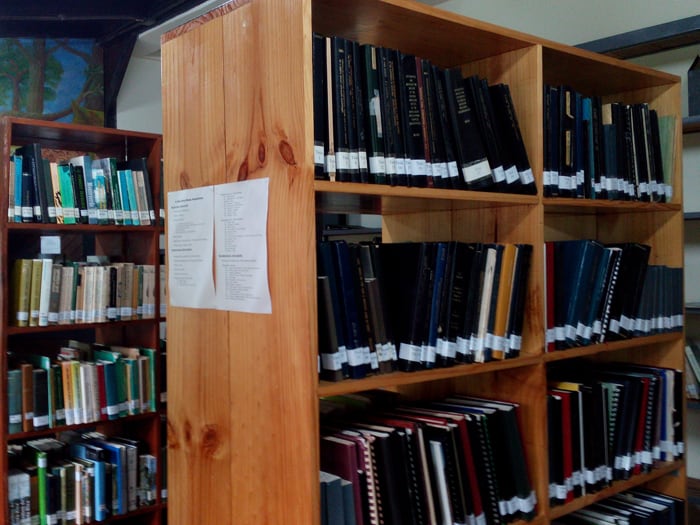

Carlos was especially proud of La Selva’s library, which contains all the master’s and Ph.D. theses that were ever done based on research conducted here.

“Out of La Selva alone, we have published 4,500 papers and books,” he said. “With 300 researchers just out of this site, that’s [currently] about 200 to 240 papers a year. That’s a paper every two and a half days.”

The library also contains all the books that go with all the courses that have been taught here, and the projects done by the students, dating back almost 50 years.

“You say, OK, howler monkeys, how many student projects on howler monkeys have we had? And it will give you all this, year by year, and you can extract data from it and then see trends from the ’70s, the ’80s, the ’90s and so on. So it’s a very good reference,” he said.

Carlos said La Selva never closes. “It’s open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. The coffee machine is never off because people are working 24 hours. Bat people are going to be out all night, and people who work with amphibians are out all night.”

He said the staff of 75 works in three shifts — Monday to Friday, weekends, and the night shift.

“What you’re seeing here is the largest laboratory in the world,” he said, “1,600 hectares of land, studied in many ways, from virus and bacteria and fungi to whole ecosystems. … Our understanding of climate change in the tropics came from here.”

Carlos recalled a recent conference in which multiple distinguished scientists opened their presentations by referring to how they started their research at La Selva.

“This has been the incubator of most of the knowledge we have on tropical biology,” he said.

IF YOU GO

Getting there: From San José, take Highway 32 toward Limón through Braulio Carrillo National Park. After crossing the Río Sucio, take the first major left — Highway 4 toward Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí. About 3 km before Puerto Viejo, look for the sign pointing left toward La Selva. The unpaved road to the station is about 1 km. Four-wheel drive is not necessary.

Rates: $95 per person single, $90 per person double, including all meals and taxes in high season. In low season, $80 per person single and $76 per person double, including all meals and taxes. Details here.

What to bring: Hiking boots or closed-toe shoes, rain gear, insect repellent and a flashlight or headlamp.

The Tico Times checked into La Selva anonymously and paid full price for lodging and food.