The telephone rang at 8:30 in the evening on May 30, 1984. The young woman in San José, Costa Rica answered. An officious voice came from the other end. “Hello, my name is Cecilia Alvear, I’m calling from NBC News in Miami. There’s been a bombing at a press conference of rebel leader Edén Pastora on the Nicaraguan side of the San Juan River. Can you hire a camera crew and get up there as soon as possible?”

“Well, I don’t know, it’s kind of late, everything is closed,” said the woman.

“I was told you were someone who could get things done,” came the curt reply.

That’s how Lyle Prescott got into the television news business.

Prescott came to Costa Rica as a University of Pennsylvania exchange student to study biology with the renowned U. Penn. biologist Daniel Janzen, studying the recovery of deforested ecosystems in the northern Costa Rican Santa Elena Peninsula.

She fell into journalism during the Sandinista Revolution when northern Costa Rica was abuzz with Sandinista activity. The rebels used Costa Rican territory to launch attacks against the regime of dictator Anastasio Somoza and also received arms from Cuba through Costa Rica where the support for the Sandinistas was overwhelming, practically unanimous.

Prescott worked as stringer for various news organizations in the final stages of the Revolution and rode into Managua on July 19, 1979 when the Nicaraguan capital finally fell as the triumphant Sandinistas celebrated the downfall of the 43-year-old Somoza tyranny.

Prescott also did work for The Tico Times, Costa Rica’s English-language weekly newspaper. The Tico Times was a training ground for young journalists from the U.S. and Europe and Tico Times journalists also served as a source of stringers for international media. The Tico Times was an obligatory stop for foreign correspondents traveling through the region who relied on the newspaper’s journalists to put them in touch with the local political scene.

Following the Sandinista victory, a number of news agencies sent representatives to reside in Costa Rica, which was a “safe country” without warfare which the journalists could use as a base.

Among the reporters to make Costa Rica their home were Joe Frazier from the Associated Press, whose wife, Linda, went to work for The Tico Times, Reid Miller also of the Associated Press, whose wife Pauline Jellenick, also worked with AP, Bob Rivard from the Dallas Morning News, whose wife Monika, also a journalist, contributed to The Tico Times, husband-and-wife freelancers Martha Honey and Tony Avirgan and John Moody from Time Magazine.

But as far as the major international news agencies were concerned, Costa Rica was relatively “off the map” which is why NBC had no crew in Costa Rica the day of the La Penca bombing.

The night she was assigned to cover the bombing at Pastora’s jungle stronghold at La Penca in southern Nicaragua, Prescott lived up to her reputation. She rousted the owner of a video supply company to rent equipment, found a cameraman from among the students at her husband Alberto Moreno’s University of Costa Rica visual arts class, and recruited Alberto to be sound man.

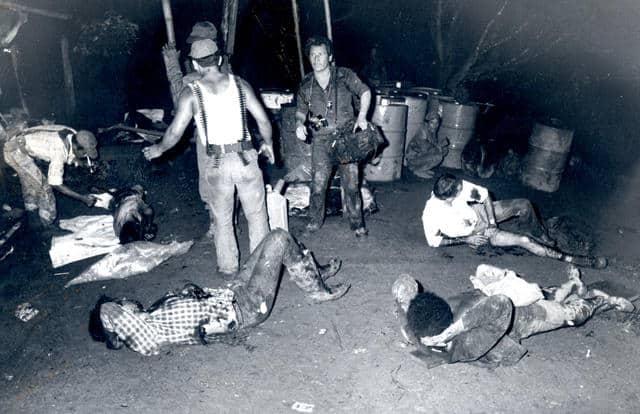

By midnight, the makeshift news crew was on its way down the fog-shrouded mountain road to Ciudad Quesada in northern Costa Rica, where about two dozen journalists, many of them critically injured, were being evacuated from the bombing scene by dugout canoe and rushed in ambulances to the San Carlos Hospital.

In the chaos immediately following the bombing, no one knew who had placed the bomb, or even if there was a bomb. Some speculated that the press conference had been attacked by a Sandinista rocket-propelled grenade, since following the explosion, the sound of small-arms fire filled the night as panicked rebels fired their weapons wildly into the surrounding jungle.

Among the wounded was Miller of the Associated Press, who had multiple shrapnel wounds. ABC News cameraman Avirgan had holes in his side and the skin on the fingers of one hand burned off. Roberto Cruz, correspondent for the Chinese News Agency Xinhua, would lose an eye and a leg in the bombing. Veteran Costa Rican journalist Carlos Vargas suffered a shattered leg.

With camera rolling, Lyle’s crew caught one scruffy bearded journalist, apparently unhurt, leaving the hospital in a car. Earlier, the well-built journalist had been captured by a photographer sitting calmly in a hospital chair, smoking a cigarette, a bandage on his hand.

It was the only close-up of the “photographer” and became the photo used for posters and paid advertisements in newspapers around the Americas for information on the suspected bomber.

A Costa Rican police investigation would eventually ascertain that this man, who went by the false identity of a Danish journalist named Per Anker Hansen, had brought the bomb to the press conference in a camera case. But for three days after the bombing, everyone who had attended the press conference was suspect—and the bomber had ample time to disappear.

News photographers had captured images of “Hansen” along with the other journalists traveling up Costa Rica’s Sarapiquí River, which empties into the San Juan, in outboard-powered dugouts. The surviving journalists remembered the “Danish photographer” fussing over his large metallic camera case which he had wrapped in plastic, trying to keep it dry.

The bomber’s intended target, the colorful, charismatic Pastora, met the journalists as they arrived at the hut on stilts in the riverside clearing known as La Penca.

The group entered the hut and gathered around a chest-high table in the middle of the room. TV photographers caught images of “Hansen” leaving the table and making his way out of the hut.

Shortly thereafter, a blinding flash accompanied the deafening roar of an explosion. The “photographer” had detonated a bomb by remote control. Photos of the ensuing chaos showed him sprawled on the ground, apparently feigning shock. He was aboard one of the first boats to leave the scene.

Pastora, quickly evacuated by his lieutenants, escaped with his life, wounded in both legs.

Three journalists, Linda Frazier of The Tico Times, Evelio Sequeira, cameraman for Costa Rican Channel 6 TV, and his sound man, Jorge Quirós, were not as lucky. All died, along with two of Pastora’s guerrillas. The bomb severed both of Frazier’s legs at the knees. She was placed on the last boat leaving the scene and died en route to Ciudad Quesada.

Frazier’s editor, Dery Dyer, had pleaded through the night with the U.S. Embassy to send helicopters from the Panama Canal Zone to the scene to evacuate the wounded. She was assured several times in the course of the night by U.S. Consul Lynn Curtin that the helicopters were on their way. They never arrived.

The bomber, who had been treated for a superficial, apparently self-inflicted cut on his hand when he arrived at the hospital, returned to San José, checked out of his hotel, walked into the crowded downtown street and vanished.

In the ensuing years, the saga of La Penca would occupy the attention of journalists from around the world as the press struggled to solve the riddle of the bombing, while navigating the combustible ideological minefield created by the story.

Much of the attention of the investigations focused on Pastora’s background that made him enemies on all sides of the Nicaraguan war.

Pastora was a hero of the Sandinista Revolution that overthrew Somoza. In 1978, the flamboyant revolutionary led the takeover the Nicaraguan Parliament, holding Nicaraguan law-makers hostage until Somoza freed a number of Sandinistas being held in Somoza’s prisons.

But when the Sandinistas overthrew Somoza, the Sandinista leadership marginalized Pastora, giving him a secondary role as vice minister of interior. And when moderate members of the Sandinista government left or were forced out with the Marxist turn of the Sandinista junta, Pastora left with them.

Pastora laid low for about a year before declaring his decision to mount an armed opposition to the Sandinistas from the “southern front” out of Costa Rica.

Costa Rica had been a second home to Pastora during his years as an anti-Somoza revolutionary. During periods he would make a living as a fisherman in Costa Rican village of Barra del Colorado on the Atlantic Coast near the mouth of the San Juan River which separates Costa Rica from Nicaragua.

Despite his new-found dislike of the Sandinistas, Pastora refused to unite with the U.S.-backed Contra rebels fighting out of Honduras. The leadership of the Honduran-based CIA-backed Contras was made up of members of Somoza’s hated National Guard and Pastora vowed to do battle with them once he threw out the Sandinistas.

The CIA intermittently provided arms and supplies to Pastora, but only enough to provide an enticement to join with the Contras in the north. But the relationship with the CIA remained decidedly hostile. At one point, as a taunt, a CIA dropped a shipment of large boxes filled with Kotex. Pastora alleged that this recalcitrance led the CIA to try to force him join the Honduran-based Contras or quit the battle and leave the southern front to someone more pliable.

The spy agency found a candidate for the southern front leader in a former Managua car salesman named Pedro “El Negro” Chamorro, but Chamorro was unable to muster much of a force to replace the Pastora.

Reporters in Costa Rica and Nicaragua were following these developments closely and Pastora called the La Penca press conference to denounce the CIA for pressuring him to unite or else.

So in the wake of the La Penca bombing suspicion immediately fell on the CIA.

Investigating the Bombing: Honey and Avirgan’s Crusade

Martha Honey and Tony Avirgan were husband-and-wife journalists who came to Costa Rica in the early 1980s to cover the regional wars for various news services. Tony was a cameraman who worked variously with ABC News and CBS News on a freelance basis and among Martha’s strings were The New York Times.

The day of the La Penca bombing, Honey had a front-page story in The New York Times about the CIA pressuring Pastora to join the FDN or quit the fight.

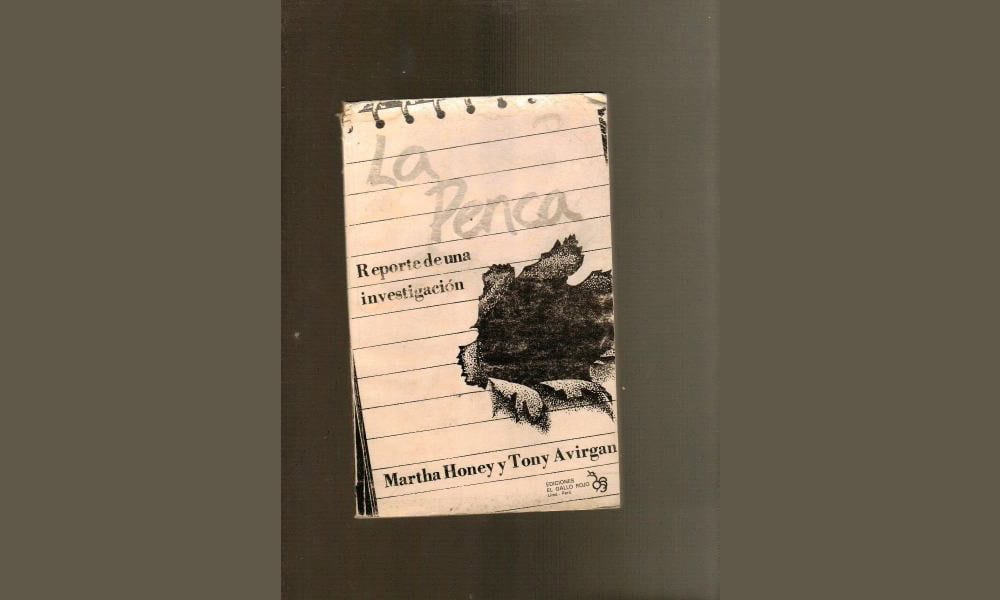

Following the bombing, Martha obtained a grant from the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists to investigate the attack.

The publishers of The Tico Times, Richard Dyer and his daughter, Tico Times Editor Dery had hoped that local and international news agencies could form a consortium to solve the La Penca mystery.

But Honey and Avirgan had a reputation among journalists of putting their political views and sixties-style activism before their journalistic objectivity—generating their own drama and becoming part of the story they were covering—and any chance of cooperation among the big guns of international journalism to find the La Penca bomber vanished when Martha was awarded the grant.

It didn’t take long for Honey’s investigation to focus on a conspicuous target: a rancher originally from Indiana by the name of John Hull, a man in his early 60s.

Hull came to Costa Rica in the 1960s and began farming near Ciudad Quesada in the northern part of the country. He ended up with a considerably large farm in the area known as Muelle de San Carlos.

In time he also came to manage other farms in the northern Costa Rican region belonging to absentee U.S. owners.

When the 80s rolled around and the Reagan Administration set its sights on overthrowing the Sandinista government, Hull was ideally situated to assist the CIA in setting up the southern front: He owned or had access to large acreage of land where Contras could train and his land and those that he managed contained airstrips to which arms could be flown.

Apparently believing himself immune to official scrutiny, Hull, along with several other U.S. anti-communists operating in northern Costa Rica, were conspicuous in assistance to the anti-Sandinista rebels, making themselves symbols of U.S. meddling in Costa Rican and putting Hull at odds with newspapers like The Tico Times with whom he clashed over the weekly’s reporting of his pro-Contra activity. Hull’s lack of discretion made him an easy target for Honey.

In early 1985, by apparent chance, Honey’s secretary Julia Meeks ran into a carpenter named Jorge Rojas Chinchilla at a restaurant near Meek’s San José home who named Hull as one of the intellectual authors of the bombing.

Rojas was to become Honey’s prime source for her La Penca investigation. The carpenter struck up a conversation with Meeks and told her about a young Contra he had met who had told him he had visited John Hull’s farm and had overheard Hull and a Cuban-American named Felipe Vidal admit to planning the La Penca bombing. The two Contra supporters were also involved in trafficking cocaine, said the source. Rojas said he knew the man only by his first name, David.

Meeks told Honey and Avirgan the story. The journalists interrogated Rojas and repeatedly asked to contact David directly, but the carpenter insisted that the Contra feared for his life and would speak only with Rojas during carefully prearranged secret meetings.

According to Rojas, David was ultimately murdered.

Rojas received death threats and was forced to leave Costa Rica for Canada, but not before being the prime witness at a libel trial brought by Hull against Avirgan and Honey. After a fiery trial before a packed courtroom the court absolved the journalists.

The trial was the beginning of trouble for Hull. Costa Rica’s judicial authorities were beginning to focus on the many accusations brought by Avirgan and Honey against the Indiana farmer, which eventually led to formal charges against Hull for murder in the case of La Penca, drug trafficking and “hostile acts,” a statute designed to protect the Costa Rican state against acts of subversion.

Once, commenting on vagaries of dealing with a CIA that was constantly changing its mode of operations, Hull told a reporter for United Press International, “I never knew when things were going from over to covert to pervert.”

If nothing else, the charges brought against Hull and Vidal showed the independence of Costa Rica’s judicial authorities who dared to indict U.S. government agents.

Honey ended up writing a book called Hostile Acts, a virtual dictionary of acts by U.S.-backed agents, both CIA operatives and anti-Sandinista independent operators, who undermined Costa Rica’s policy of neutrality in their efforts to overthrow the Sandinista.

The book is actually two parts. One which outlines the effort by the United States Agency for International Development (AID) to keep Costa Rica’s economy afloat while weaning it off of foreign aid and a second section detailing the many covert operations and operatives launched by the U.S. in support of the Contra cause in violation of Costa Rica’s neutrality stance.

The book attempts to draw a parallel between U.S. AID’s programs and the covert efforts to assist the anti-Sandinistas from Costa Rica. But it’s hard to construe aid in the amount of a billion dollars over a decade to save the Costa Rica’s tanking economy as a “hostile act” even if the aid was aimed at helping dismantle Costa Rica’s state-led economic order.

But the book did serve to demonstrate how U.S. foreign policy toward Costa Rica was at cross purposes, propping up the country’s democratic institutions with one hand while undermining Costa Rican democracy with its covert actions against the Sandinista government with the other.

A Confrontation Over Evidence

At one point, Honey and Avirgan found the tables turned and themselves accused of drug trafficking. One day the couple’s housekeeper went to retrieve a package addressed to the journalists at the central post office in San José. Police were waiting, in possession of a kilo of cocaine, along with a addressed to the Avirgans by “Tomás” (presumably Sandinista Junta member Tomás Borge) which said that U.S. Sen. John Kerry was waiting for the package in Miami.

The clumsy, not to say absurd, nature of the attempt to frame the teetotaling journalists did not stop the cops from detaining the housekeeper, whom they took to the couple’s house in an attempt to get inside and search it. Meeks called The Tico Times, in hopes that the presence of the press would keep the police from searching the house.

Tico Times reporter Beth Hawkins and I grabbed a cab and arrived to see the couple’s housekeeper cowering in the rear of an unmarked cop car, Avirgan standing halfway inside it in an effort to prevent its departure. Honey, meanwhile, was confronting a plainclothes policeman. Avirgan and the cop also traded epithets, with Avirgan calling the cop a maricón (fag), which prompted the policeman to grit his teeth and place his hand on the revolver strapped to his side.

The couple’s lawyer, Otto Castro, arrived and demanded to see a warrant the cops could not produce. Then he pleaded plaintively with the couple to let the policemen take the housekeeper. “We can free her later,” he said. “What they want are documents.”

Avirgan relented and the cop car took away the housekeeper. The journalists piled into Castro’s car and headed for the courts, where the lawyer would fight off any search warrant with the argument that Honey and Avirgan were clearly set up. As he’d predicted, the charges against the housekeeper and her employers were dropped and the housekeeper released that day.

Aftermath and Revelations

If anyone can be said to have won the escalating battle between left and right represented by the Honey-Avirgan feud with Hull, it had to be the former, given that Hull and Vidal were accused of masterminding the La Penca bombing, drug trafficking and hostile acts, while the husband-and-wife journalists went on to work for public advocacy groups based in Washington.

Vidal, a Bay of Pigs veteran, who helped the Contras in Costa Rica with logistics before removing himself to Miami after the charges pleaded his innocence to the press. The murder charges filed against Vidal prevented the Cuban-American from obtaining a job for many years.

Hull was briefly jailed for the charges, before claiming chest pains and being removed to a local hospital.

Meanwhile, Miami Herald reporter Juan Tamayo met with a member of the Argentine People’s Army in Paris, who told him that he recognized “Per Anker Hansen” as part of the guerrilla group and said he helped train Nicaraguan fighters who were members of the Sandinista militia.

Around the same time, Doug Vaughn of the public interest group the Christian Institute found a fingerprint and a photograph of the attacker in a motor vehicle department in Panama.

Juan and Doug joined forces and went to Buenos Aires, where, with the help of two journalists, they found a photo of the attacker along with a fingerprint in a police file.

They took the fingerprint to an expert in Miami and found a perfect match: Per Anker Hansen was actually Vital Roberto Gaguine, a member of the leftist movement. The Argentine People’s Army was apparently killed in a suicide attack in 1985 at the Argentine military base in La Tablada.

The mystery was solved; the Sandinistas succeeded. Or not? For Martha Honey and Tony Avirgan, circumstantial evidence such as the testimony of carpenter Jorge Rojas remained important.

But the decisive factor was the testimony of Swedish journalist Peter Torbiornsson, who, guilt-ridden, traveled to Managua to admit that Sandinista commander Tomás Borge had convinced him to take Gaguine to Pastora.

Torbiornsson says he knew he was traveling with a spy, but had no idea he was traveling with a terrorist.

The proof is irrefutable: the Sandinistas did it.

Still, some, including Linda’s husband, Joe, think that the United States somehow had something to do with it, even if it was knowing about the bombing and allowing it to happen.

About the Author

John McPhaul Fournier is The Tico Times ‘former editor