The first book I ever tried to read in Spanish was Robert Vesco Compra una República. It was 1991 and I was a few months into my life in Costa Rica. Learning Spanish by listening to the radio, overhearing conversations on the street, making verb charts, drinking at the cantina and talking with the locals, I understood fragments of conversation and spent a lot of time smiling, nodding and saying “claro que sí” or “¿verdad?”.

I was ready to read in the language and picked up the Vesco book at a downtown San José bookstore. His name was only vaguely familiar to me at the time—he’d once made U.S. news for illegal campaign contributions—but as I struggled through the book, written by Costa Rican journalist Julio Suñol, I became aware of the premise. Vesco really had bought his way into Costa Rica, using part of the $200 million he’d stolen when working for an investment firm. His presence here ignited such controversy that a new president ran on a promise to evict him—which he did upon taking office. For years, however, Vesco lived in Costa Rica as a guest of the government, funneling millions into public projects and the pockets of officials while safely beyond extradition.

Vesco was long gone by the time I read the book, but there are always other mini-Vescos ready to fill the gap. That same year I attended a meeting of a group selling residency in exchange for a $50,000 investment in teak plantations. Normally teak takes around 25 years to mature, but this group promised huge, almost instant returns. Of course, the day came when the teak boys packed up and left with the investors’ money. Similar stories followed: “The Brothers,” “The Cubans” and “The Vault” all promised enormous returns on jungle timber, then closed the books and disappeared with as much cash as they could carry, leaving trusting investors with depleted net worths.

Then there are the “Trust me—I’ll build a condo” schemes. Armed with little more than an idea and a blueprint, promoters sniff out potential investors like hogs rooting for truffles. I know of three different projects that never got off the ground, even though plenty of “security deposits” were paid up front. Costa Rica is also home to sweepstakes boiler rooms that advertise openly on help-wanted sites yet prey on the elderly, deceiving them out of their money. Although I’ve never worked for one of these operations, international busts over the years and convictions of several Ticos in U.S. prisons attest to their reach.

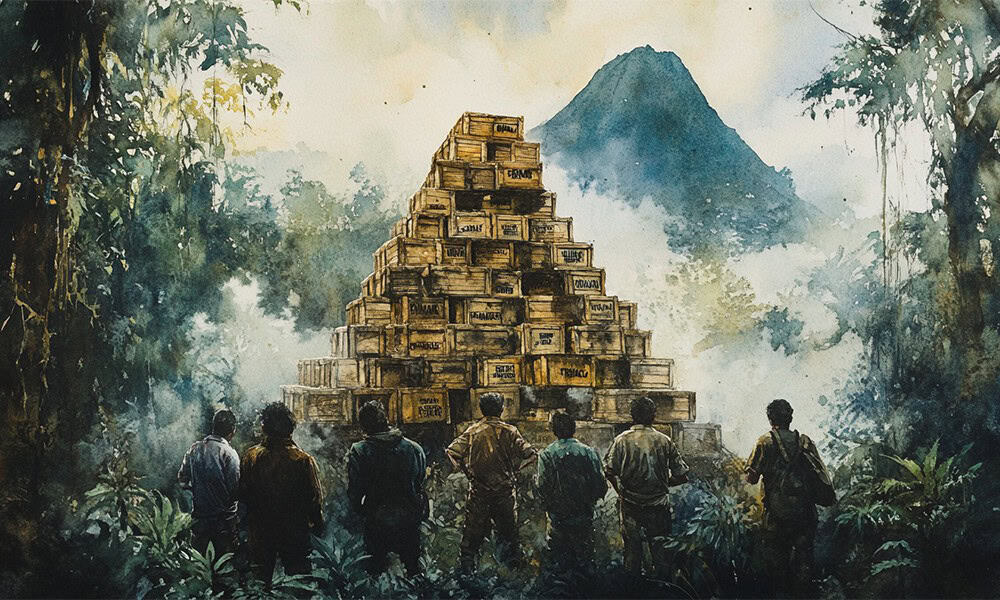

Closer to home, small-scale operations persist under the principle of getting in on the ground floor and finding enough “suckers” to make it work. A couple of family members lost money investing in one called “La Pirámide,” which functioned exactly like a classic pyramid scheme: early participants profited from new investors’ funds, but those at the bottom lost everything. Right now I’m following someone who for years has moved from place to place in Costa Rica, setting up legitimate-looking businesses and then scamming victims out of their savings. Complaints have been filed, but to my knowledge he has never been brought to justice—so it often goes here.

I write this in the wake of the latest revelation that a local bank was involved in laundering a cool $100 million. “What a surprise,” said no one. Mix lax law enforcement, a culture that turns a blind eye to dubious financial propositions, plenty of people ready to be separated from their money, and no shortage of sociopaths happy to scam you—and welcome to the jungle, where the fiercest predators are human.