Rio Virilla is not one of the major rivers of Costa Rica. At about 55 kilometers in length, it meanders through the Central Valley, passing through mostly urban stretches, spanned by small bridges and overpasses. Throughout much of its course, it would run largely unnoticed below the highways, were it not for the signs marking its presence. Yet this unassuming river carries with it a great history as two of the best known events in the existence of Costa Rica occurred on her muddy banks.

The first was in 1835. The republic of Costa Rica had gained independence from Spain fourteen years earlier. But peace did not reign throughout the land. Following freedom from their colonizers, there was an ongoing fight over the location of the capital. Cartago had been the capital since the 16th century but the long argument turned into a civil war in September, 1835.

Called La Guerra de la Liga (The League War), the aftermath resulted in the city of San Jose triumphing over the triumvirate of Alajuela, Heredia and Cartago, to become the new capital of Costa Rica. The crucial battle took place on October 28, 1835, on the banks of the Rio Virilla. The forces from San Jose proved victorious and the capital was claimed. Like the better-known civil war 113 years later, it was over quickly and the defeated went back to their daily lives.

Almost a century later, the most famous disaster in the nation’s history took place, also on the banks of the Virilla. It was the morning of Sunday, March 14th, 1926. Trains full of festive men, women and children, all dressed in their Sunday finest departed Alajuela on a train bound for Cartago. The excursion was organized by a priest named Claudio Volio Jiménez, and the purpose of the trip was to raise funds for a home for the elderly in Cartago.

The train, belonging to the Northern Railway Company, made a stop en route in Heredia. Because more tickets had been sold than there was space on the train, the decision was made to use a larger train consisting of the locomotive, six passenger cars, and the caboose. Over 1,000 passengers had boarded the train with all seating taken and the aisles filled with the last arrivals, all standing.

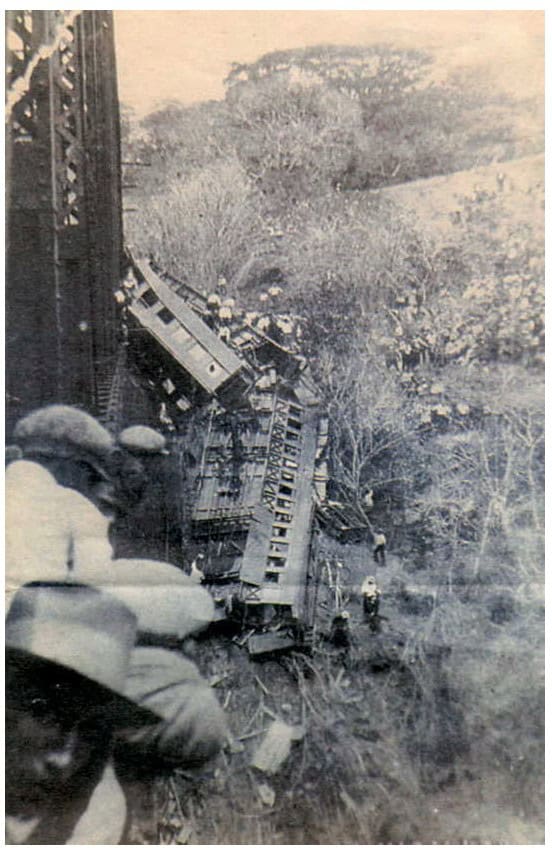

On the final leg from Heredia to Cartago, at a little after 8 in the morning, the engine and the first three cars negotiated a curve just before entering the bridge over Rio Virilla. Here, the engineer accelerated to gain momentum as at the other end of the bridge was an uphill slope. Unfortunately, the driver failed to notice that the last of the cars had not yet crossed the curve. The acceleration, added to the excessive number of people in the cars, caused the fourth car to lean to the left and go off the tracks, dragging along the two cars that preceded it and that had not yet reached the bridge.

The last car crashed onto a pasture next to the train tracks. The fourth car was the car of death: It derailed completely and fell from a height of sixty meters into the northern ravine of the Virilla River canyon, instantly killing all the passengers who were inside. The next to last car crashed into the bridge structure and bent in half, leaving one part on the bridge and the other hanging over the cliff.

The final death toll was 385 people, mostly humble farmers and laborers. The Costa Rica government declared three days of national mourning. The newspapers of the day covered the tragedy in the florid and graphic style common to the time.

From the newspaper La Prensa came the headline “La Pavarosa Catastrofe de Ayer” (Yesterday’s Dreadful Catastrophe). The translated description of the aftermath read: “We write these pages with our hearts still oppressed and our thoughts stunned by the magnitude of the catastrophe.

Alajuela, the sober and austere Alajuela, the most spiritual and levitical town of the whole republic has been destroyed and annihilated ….. it seems more like a tragic Dantesque nightmare. ……..human beings pinned to the timbers and ironworks like butterflies that are nailed with pins, each piece of iron is a relentless scythe, each splinter is a spear, piercing breasts, opening bellies, crushing heads, cutting necks, breaking legs and arms.” The writer concludes by calling the scene ‘una carniceria horrible’.

So flows the Rio Virilla, the murky watershed of the Central Valley, and carrier of two unforgettable pieces of Costa Rican history.