The jungle protected them for centuries and centuries, but the construction of roads, erosion and agricultural work endanger the mounds of a colossal Amazonian civilization some 2,500 years old in eastern Ecuador.

Along 300 km2 in the Upano valley, south of the Amazon, there is a “lost city” found in 1978 that shows evidence of ancient settlements in the rainforest region, of different sizes and connected by roads.

“It was thought that they were (structures) natural and were cut to build roads. So it is urgent (…) a protection plan, not only for research,” said Spanish archaeologist Alejandra Sánchez, who has been investigating this heritage for a decade.

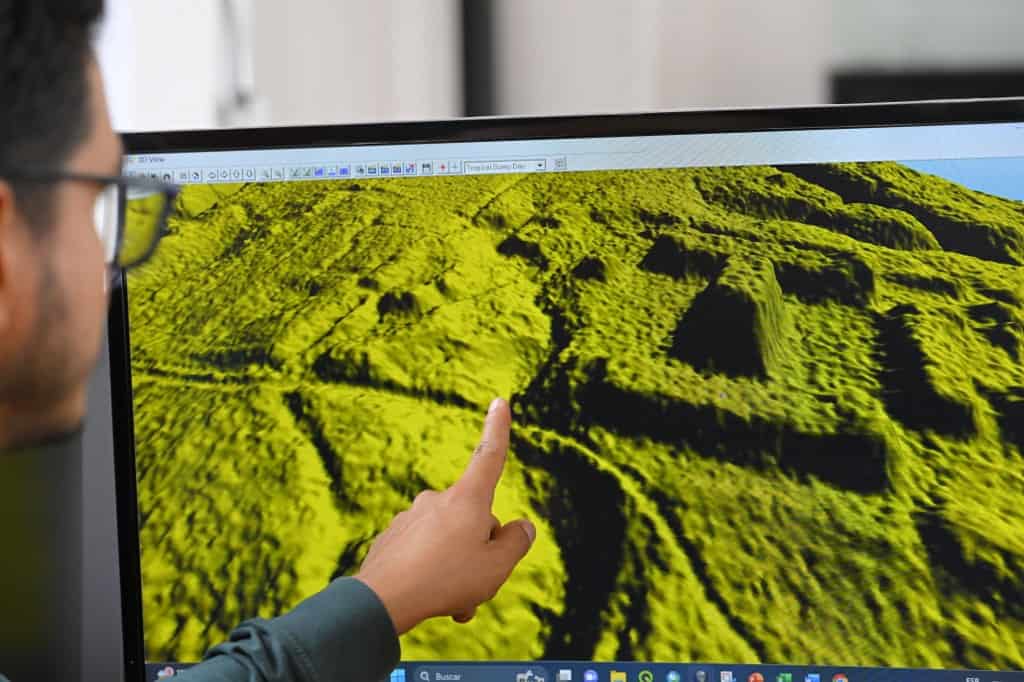

With the help of a state project in 2015, she and other archaeologists used information yielded by sophisticated technology to identify some 7,400 mounds in L, T, U, square, rectangular and oval shapes.

But when the archaeologist from the University of Valladolid visited the area years ago, she found that some of these earthen giants had succumbed to the power of modern machinery: “They were damaged by the passage of roads.”

Erosion, deforestation and agriculture also threaten the structures up to four meters high and about 20 meters long. “With the rains, with the wind, with the plows, etc., they are destroyed very easily,” explains Sánchez. In addition, the Upano River, cradle of the indigenous culture of the same name, is prey to voracious illegal mining.

As a protective measure, the state National Institute of Cultural Heritage (INPC) will begin by marking the boundaries of the complex in the province of Morona Santiago (southeast).

“The envy we had of the archaeological heritage of our Peruvian neighbors or our distant Mesoamerican neighbors, we have it here, in the Upano valley, in quantity, in grandeur, in history, in cultural manifestations,” says Ecuadorian archaeologist Alden Yépez from the private Catholic University of Ecuador.

Lost city

In 2023, Sánchez and Argentinian Rita Álvarez presented an analysis of the images obtained after an overflight using LiDAR (Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging) technology, which uses laser to detect terrain irregularities. “The conservation and enhancement actions have changed a lot,” said INPC director Catalina Tello.

For Tello, understanding the archaeological findings should occur “in context”, in this case including the Shuar and Achuar indigenous people who “have safeguarded and cared for all these vestiges”.

Upano rose to fame in January, when the journal Science published an article by Frenchman Stéphen Rostain, who conducted excavations in the 1990s.

The INPC and archaeologists such as Yépez recall that the structures have been analyzed for four decades, when the story of their existence reached the ears of Father Pedro Porras. The priest and also Ecuadorian archaeologist described them in the 1980s as a “lost city”.

The tip of the iceberg

Pots with reddish dyes and finely decorated, a piece of carved volcanic rock in the shape of half animal and half human, and other pieces found by the priest are exhibited at the Weilbauer-Porras museum at the Catholic University (PUCE) in Quito.

The center also houses maps and black and white photographs of Porras in which the geometric mounds that stand out from the ground can be distinguished. The most modern findings are in the INPC documentation center, which holds the images generated by LiDAR.

For Yépez, also a professor at PUCE, the more than 7,000 mounds described a year ago by Alejandra Sánchez are the “tip of the iceberg” of a civilization that could have been even larger.

The researcher estimates that the mounds extend over some 2,000 km2 around the Upano, Palora and Pastaza rivers, where there are signs of settlements.

Amazon Venice

The findings described so far of the Upano culture show political, economic and religious organization typical of great civilizations. “That idea that the Amazon was an unpopulated space” or only inhabited by nomads is dismissed, adds the INPC director.

Yépez, who continues to investigate the area, works with other scientists analyzing the atmospheric data of the place where rain is frequent. Unlike his colleagues who speak of structures connected by roads, Yépez believes that these are “huge interconnected drainage systems.”

“One of the fundamental purposes is to evacuate the vertical precipitation, so there is a direct, wonderful correlation” with the atmospheric characteristics of the area, explains the researcher.