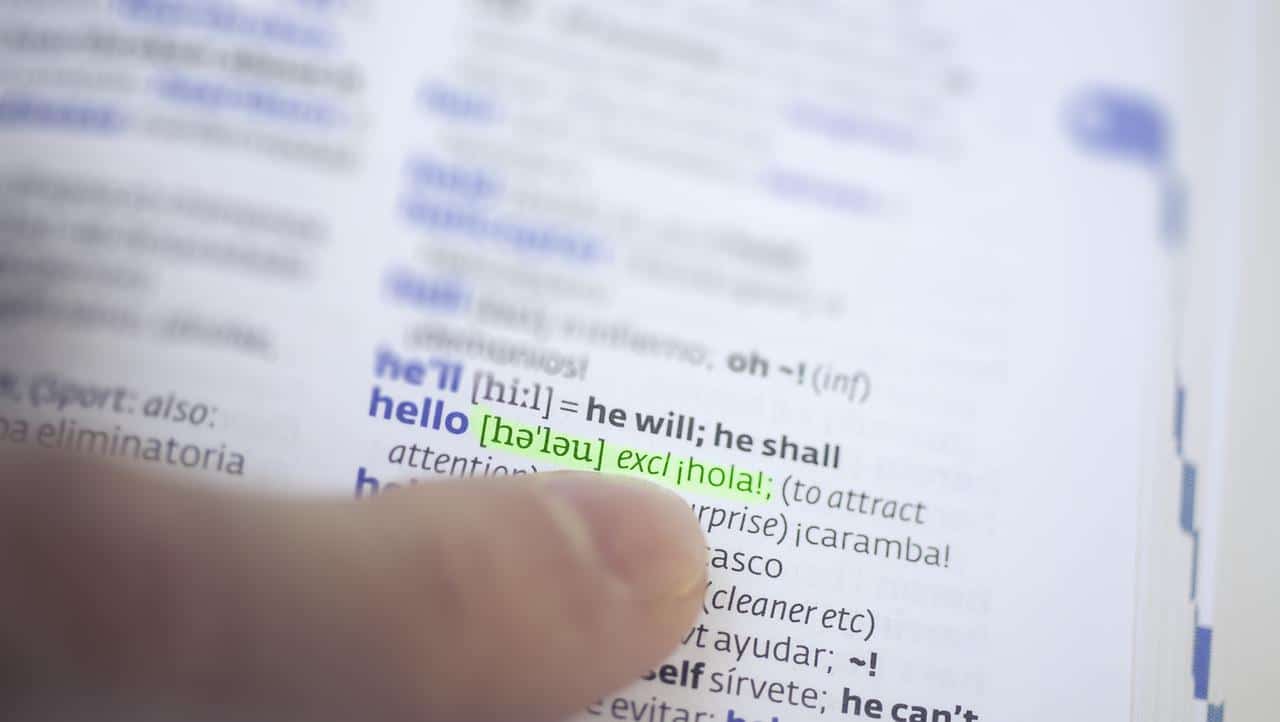

No matter how well we may learn a second language, there are always words and expressions that are going to give us grief. Here are some that continue to bother me.

Corny

“Corny,” as most of you know, is a word describing the kind of humor that comes from the allegedly rustic, ignorant and simple folks who cultivate corn.

The most common translation provided of “corny” into Spanish is “cursi.” In fact, if you look it up in either direction on Google Translate, that’s what you will get.

In actuality, although “cursi,” is often used in the context of “silly,” and its technical definition is “said of the person who presumes to be refined and elegant without being so.

If we consult the definitive source, the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy), Cursi is defined as (My translation):

- adj. Said of an artist or a writer, who pretends to possess refinement or elevated sentiments.

- adj. colloq. Said of a person who pretends to be elegant without being so.

- adj. colloq. Said of something ridiculous and tacky that tries to appear elegant or luxurious.”

In other words, pretentious, self-important, superficial.

What is probably the best translation, at least here in Costa Rica, involves the word “Polo”: defined in Asi Hablamos as (my translation) “person of speech or antiquated customs no longer accepted by modern society.” Usually reserved for people of peasant origin and not accustomed to cosmopolitan ways, the term also applies to people with ridiculous or old-fashioned customs.

Maicero

A similar word is “maicero,” which, like “corny,” comes from the word “corn” (maiz). However, neither of these words are adjectives, and they do not connote any kind of silly humor, but refer to those whom some people call “country bumpkins.”

I go into such detail about one word only to illustrate how complicated translation can become and how easily we can be misunderstood.

I don’t like clutter, but in Spanish there doesn’t seem to be any specific word for “clutter.” It is usually translated as “desorden,” but this simply means “disorder” or “mess,” and can just as well refer to a dirty counter top as a table with too many knick-knacks.

There are two other words, both verbs, that Google Translate offers us: “atestar,” whose first meaning is “testify,” and whose second meaning is “to stuff full,” and “apiñar,” which means “to crowd” or “to cram together.”

Though there is no noun for it,“apiñar” seems to come closest in meaning, but, if we try to say, “Esta mesa está apiñada,” it will be interpreted as “this table is squeezed or crowded against something.”

In the end, the only word that really works (but is rarely found as a translation in a dictionary) is “congestionar,” or “to congest” and its noun “congestión.”

Given all this, I think I’ll just stick to saying, “!Húacala! Mucho chunche!” (“Húacala means “Yuck,” and “chunche” is a slang word for “stuff.”)

Consciencia

I love to talk about metaphysics, especially the nature of consciousness. In Spanish, however, the words for “consciousness” and “conscience” are the same: “la consciencia.”

This means that every time I want to discuss human consciousness in Spanish, I must first explain that I mean “consciencia” en el sentido de ‘ser consciente’ y no en el sentido moral (“consciencia” in the sense of “being aware” and not in the moral sense). It’s no big deal, except that each time I say “consciencia,” I still feel like I’m saying “conscience.”

Another word that some sources give as “consciousness” is “conocimiento,” but this is even more confusing, since it generally means “understanding.”

On the other hand, the noun for “unconsciousness” is easy and clear, “el inconsciente.” Why can’t the word for “consciousness” just be “el conciente?”

Traer and Llevar

Then there is the problematic pair, “traer, and “llevar.” They are very similar in that both, aside from numerous idiomatic meanings, refer to objects moving from one location to another. However, there is a difference.

“Traer” generally means “to bring,” while “llevar” means “to carry,” or “to bring with.”

Llevar comes from Latin levāre, “to raise up,” and when it means “to carry,” it is not confusing. (Llevaba un saco en las espaldas [He carried a sack on his shoulders], Te lo llevo [I’ll carry it for you]). However, when it means “to take” or “to bring with,” it gets confusing. Llevar means “to take,” such as when an object is being taken (generally by you) to a place other than where you are.

I’m going to take the book to him. (I have the book, and I’m going to take it elsewhere to give to someone else) Le voy a llevar el libro. I’m taking my boyfriend to the party. (My boyfriend is here, and I’m taking him with me to the party.) Llevo a mi novio a la fiesta.

Traer, in contrast, means “to bring,” such as when an object is being transported to the place where you are. For example, “Ronaldo’s going to bring the book.” (He has the book, and he’s going to bring it to wherever I am.) Ronaldo va a traer el libro.

They brought the beers. (They brought the beers with them to wherever we were at the time.) Trajeron las cervezas.

What is confusing in all this is that our verb “to take” is often a translation of both words, that we often use “bring,” “carry,” and “take” interchangeably, and that, the dictionaries themselves give contradictory definitions.

Another source of confusion is the verb “tomar,” which, again, leaving aside idiomatic uses, means “to take” in the sense of “to take a hold of.”

SO TO SPEAK: Some words that continue to bother me was written by Kate Galante in 13