When Fred comes in hot, all bets are off. I had been watching Apocalypse Now for the fortieth anniversary. My mistake, apparently. Fred sounded like a Huey, and I had no recon of his logistics.

The best I could do was put a hand over my head, pretend I had a flack jacket, bend low, and mutter, “Tranquillo, Freddy boy. No moleste.” When he flew through my hair for the umpteenth time, I learned to plan my trips to the bathroom with surgical precision.

“Max, what’s up with the fucking parrot?”

“He’s a rescue bird. He’d be dead out in the world.”

“I might be dead in here.”

“You’ll be OK. He likes you, that’s why he’s so friendly.”

“You mean like friendly fire.”

“Something like that.”

Freddy had perches throughout the three bedroom apartment. My favorite was the big cage in the corner where he could be locked up safely and shit all over the Tico Times. For his other perches in the kitchen, Max would leave the cabinet doors open. Sometimes there was a paper towel spread over the counter for Fred to shit on, sometimes not.

His favorite was a wooden door that he had skillfully ripped apart with his beak, creating a nice, soft, sawdust-like nest. Max fed him breadsticks and chicken bones up there, and Freddy had created an impressive pile of wreckage at his feet.

Once a week, Yolanda la Reina de pachanga would come in to clean up the toxic waste.

At other times Freddy slept in a perch in Max’s bedroom, and then I felt relatively safe, because I could close the door. I always kept my bedroom door closed.

When Freddy came in hot, there was no telling what would happen. Maybe just buzz through your hair on his way to a perch. Or maybe he’s got some dirty love for you, and he wants to grab on to a shoulder, or the back of the neck, and hang there. And of course you’re trying not to panic and don’t want to be too forceful and shake him loose, because who knows what kind of ammunition he’s got loaded up in those claws, uh, talons. What damage he was capable of.

“How do I get this thing off me?”

“Don’t look at the monkey. You know what I mean?”

“Will that make it go away?”

“No, but you won’t see it coming. So you won’t worry about it so much.”

“Right. Good plan. See you on the other side.” Just to piss him off, I said, “Fuck you, Freddy boy.”

“Venga aqui.”

Anyway, that was not the first liability. That was just collateral damage.

I wasn’t clear if Max was a gun runner or a rum runner, but it didn’t really matter. He was trying to go legit, like everyone else. So he bought a newspaper. Mikey and I had met him in a whorehouse in Havana about seven years before. He still had the photo album on his living room table.

“I can’t believe it was seven years ago.”

“Yeah. How come you’re not dead?”

“I could ask you the same question.”

“Clean living, man.”

The first liability was the desire for a beach holiday. Because that was not going to happen. When I showed up in San Jose, Max said, “Don’t go to Limon.”

My plan was to fly to Limon, then catch a bus to Puerto Viejo, which everyone said was paradise on earth.

“Why not?”

“Narcos are shooting up the joint. Seven dead. You’d have to transit from the airport through the city center to the bus depot. Bad bet. You’re a mark.”

“OK. Next best option?”

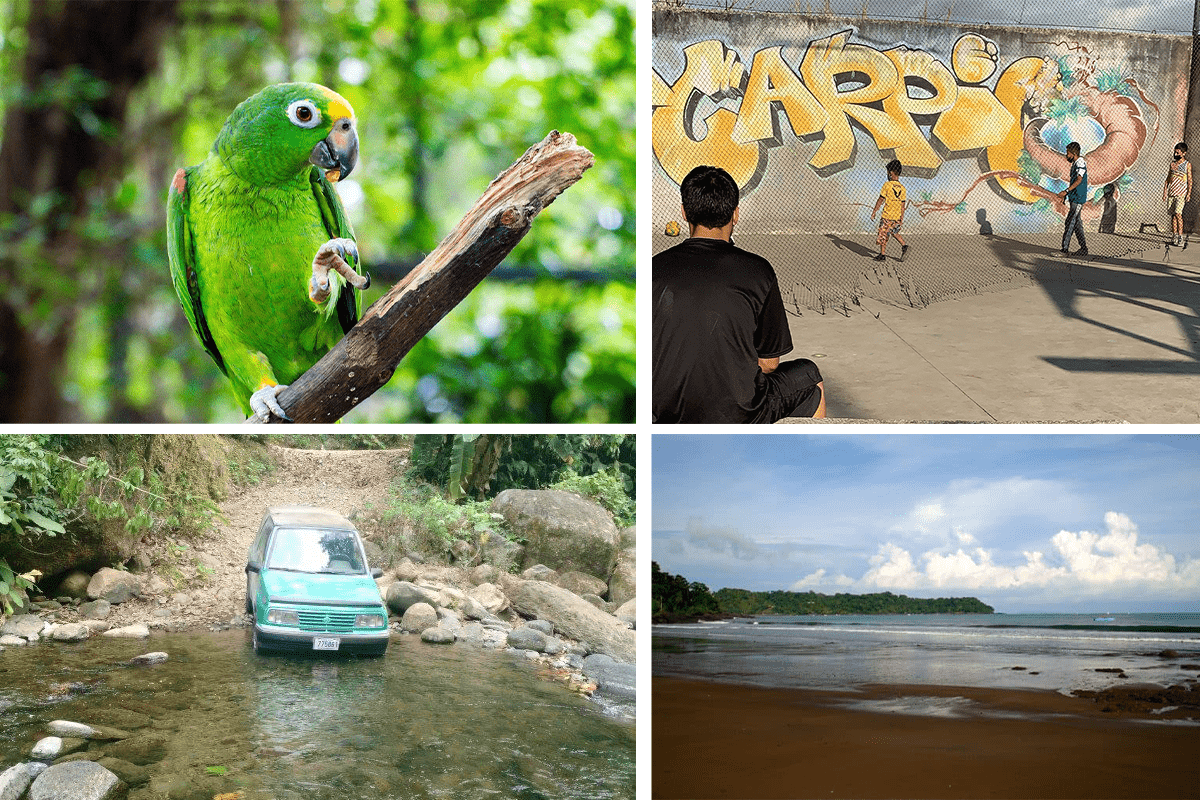

“Drake Bay. I have a house there. My wife is there with her mother. They’ll set you up. The plane drops you right on the beach.”

“Vamos a la playa.”

“I’m not going. I hate the beach. Besides, I have to work. I’ll get you a plane. Hand me the phone.”

He waits on hold for twenty minutes. The mobile app lists a flight schedule from four years ago.

“All filled up tomorrow. So you go the next day.”

“Great. Let’s get some food.”

“Let’s go to Larry’s.”

“Vamos a Larry’s.”

Larry is a fat, white, balding creature from central New Jersey in a sweat-stained wife beater. The waitress behind the bar is in a skintight sleeveless number that leaves nothing to the imagination, her eyebrows are carefully threaded, and her makeup is impeccable. Larry and I have a lot in common.

We both claimed to know Bruce Springsteen, but he didn’t know that Bruce was born at Monmouth Hospital, where my dad had been a medical intern before he met my mother in Newark during the riots. We recited a litany of places we had known. Larry was adamant that he was not from Sayerville. Someplace near Englishtown. Bruce of course was from Freehold, not Asbury Park. We chuckled over Mister Clean getting a DUI on his motorcycle for drinking tequila in the national park at Sandy Hook.

“What are you doing here, anyway?”

“Thinking about retirement.”

“Don’t you know that Costa Rica is where fat white guys go to die?”

“Yeah, I think I heard that somewhere.”

“Just look at me.”

“You said it, not me. Don’t look at the monkey.”

“What the fuck does that mean?”

“Ask Max.”

After a few drinks, Max gets up his nerve and says,

“Let’s go to La Carpio.”

“Whatever.”

“Don’t tell Karol. Last time I was there they threatened to steal her car.”

“To quote a famous newspaper man, in other words, a shit show.”

“You got it.”

“My lips are sealed.”

On the way over, in Karol’s car, Max told me that Barrio La Carpio was said to be among the most notorious sites in the country for gun violence and a wide variety of petty crimes. It had been settled by Nicaraguan migrants about forty years ago, who were fleeing the dangerous conditions in their country during the US-backed contra war. They squatted on the grounds of what was planed to be a kiddie park for a nearby hospital.

Despite this reputation, we found the population largely hospitable. Uniformed school children crowded onto busses, barefoot kids played soccer in the street, and the occasional goat wandered by. The locals bought the gringos a beer, and the favor was returned.

The kind lady behind the bar treated us each to a tasty chicken wing. Living standards were on the low side, but relatively comfortable by my experience of third world, working class neighborhoods. Open sewers ran down both sides of the street. I considered it an up-scale, Indian-style slum, until Max reminded me that everyone had guns. That was different. In India, even the police don’t carry guns.

Max is a newspaper reporter, and he likes to get his gossip fresh. We share drinks with some local shit kickers in Stetsons and cowboy boots. Max speaks Nicaraguan Pachuco, and I can’t understand a word of it. Which is good, because I’m insulated from the trouble. I’ve been in plenty of other similar situations: deaf, mute, uncomprehending. Just shut up and smile. Wear your ignorance like a blanket.

“Where did you learn to speak that shit?” I wondered out loud.

“Don’t look at the monkey.”

I sit back and smile.

“They just threatened to steal the car.”

“All in good fun.”

“Don’t tell Karol.”

The shit kickers are watching the football on TV when Max asks for the remote. He puts on Ralph Stanley playing claw hammer bluegrass banjo, and we pry ourselves up from our seats and do a little Appalachian jig in the middle of the bar. The crowd goes wild.

“Alright, let’s get the fuck outta here.”

Max has a negotiation with the lovely barmaid.

“What was that all about?

“She tried to charge me double.”

“Why?”

“She said I was a gringo and I could afford it. We made a deal.”

Somehow we got home unscathed, bought a roasted chicken in a paper bag, cheese and bread from an upscale shopping mall with prices like Whole Foods. It’s good. Fred has been waiting for me, getting stronger. I had forgotten about him.

“Venga aqui.”

“Fuck you, Freddy boy.”

He lands on the back of my neck and beer goes everywhere. We spend the evening watching Desmond Dekker videos and laughing our asses off. I will never again listen to “The Israelite” in quite the same way. We watch the war on TV. Max says, “Paste in the calico cat.” I almost gag.

The next morning we roll out of bed and make another assault on the airport.

“Hand me the phone.”

Cigarette.

“There’s a flight at eleven.”

“I’d better get moving.”

“Finish your beer.

It’s only twenty minutes to the airport, and they’re always late. I’ll call you an Uber.”

The road construction gets me there about 11:10. An armed guard takes my digital temperature and directs me to the hand sanitizer. Sansa has seriously upped its game from the last time I was there, from a tin shed with long delays to an ulta-modern, high-tech facility with record-breaking on-time departures.

“Sorry sir, the flight has left, there’s another at 3 PM, but it’s full. Would you like to go stand-by?”

I call Max. “Let’s go to Larry’s.” The return cab ride takes twenty minutes with no construction. I book a flight for 8:30 the next morning.

The chicken is still on the table.

Pablo shows up with his current girlfriend, and after a few pleasantries he drives us in Karol’s car down to Larry’s. He’s fast, he knows the place, and he keeps asking me, “Enrique, comandante, como estas?” I reply, “Pablocito, mi amor, tranquillo, cuidado, hay ninos, despacio.”

He howls his derision. He was recently in a car crash, and is just out of a neck brace, so he can’t turn his head. We come alarming close to some big busses while Max screams “Cuidado!” from the passenger side.

At Larry’s, Pablo and the girlfriend start drinking cacique. He calls her by a slang name that means someone who loves liquor. Whatever. Pablo has three kids with three different mothers, but that doesn’t really matter, because we’re only going to pick up one of them from school today. His mother is a famous singer who has a world-shaking performance this evening, and he has to baby-sit. The girlfriend is nice.

We stop at the supermercado to get the kid a snack, and while she’s in line I ask her to buy me some instant coffee for the next morning, because Max doesn’t have any. I give her five thousand colones. She keeps the change. I had already gifted her a pack of Winstons. What the fuck.

The kid, Dario, is beautiful. He is the future. Fuck his parents. Pablo is a bit scary, but the kid obviously loves him. It reminds me of coaching the under six-year old soccer team in Wauwatosa, WI.

Shit. One week in country and I’m still only in Saigon. Meanwhile, Charlie squats in the bush, getting stronger.

I get to the airport by 7:30 AM, no construction, and they put me on the early 8 AM flight. The guard at the door in Drake informs me that I only have a one way ticket to Drake, and I will not be able to get back on the plane to San Jose.

“Claro que si. Yo estoy aqui hoy. Ida solo. No quiero ir a San Jose. Hay una problema?”

“Espere, senor. Sientese.”

They only know tourists.

Karol shows up at the airport. I’m thirty minutes early, so there’s no reason she would know to pick me up on time. Airport security immediately disappears, and away we go in a grungy old pickup truck, my bag bumping around in the red clay in back, and me, Mama, and Karol packed into the front cab with the ancient driver.

She asks me in Spanish, “Did you go to La Carpio?”

“No, no, I heard it’s very dangerous, full of drugs and guns. Why would I go there?”

“Did they try to steal my car?”

“No, I don’t know, I don’t speak the language.” Plausible deniability.

“I don’t know why Max likes it so much.”

They take me up a winding, dusty road full of heavy construction vehicles. Sometimes the pickup has to back up to let the heavy rigs pass. I haven’t been on a road like this in longer then I care to remember. We reach the resort at nine.

“Give him twenty.”

I learn later that the local taxi business is a collectivo, and all trips to the airport are $10.

La Margarita is a handsome, tidy resort hotel up in the hills. It has a nice pool, seems like a long way from the beach. They put me in a king and queen two bed fuck suite with polished marble floors and a granite tub for $100. I’m thinking Tony Montana. The proprietor seems apologetic for charging me this price. It has air conditioning and a beautiful balcony overlooking the jungle, from which you can barely glimpse the sea, and it is illegal to smoke.

Mega yachts of Russian oligarchs float placidly at anchor, trailing strings of jet skis. Apparently the jet skis are used to disrupt gunboat assasins from the Mossad. While I’m contemplating the reality of all this, I wander down to the food service area and ask the bartender for a beer. He’s absolutely black, wrapped in impeccable white linen like Famous Amos. At about 9:30 AM.

“Lo siento, no hay dinero. Esta en mi quarto. Yo volvere con el.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

I snoozed for about an hour, then stumbled my way back to the pool, which was shockingly cool in this muggy heat, then wandered down the one dirt track that constitutes the town of Drake Bay. I’ve seen something like it many times before, so it wasn’t too uncomfortable. I just hadn’t seen it in a while.

It was not a beach holiday, but it was fine for today. Heavy dump trucks rumbled down the track, and you wondered where they were headed. The road was not too bad in these parts. I bought some bananas and a bag of chips from the mercado, and made it back to my pool, soaked in sweat.

La Margarita can only accommodate me for one night. My friends assure me they will find lodging for the coming days. As of 5 PM they are still skunked. It’s high season, and the hotels, like the flights, are all full. There are plenty of terrible looking backpackers with tattoos and dreadlocks squatting in hammocks up in the hills, but I did that forty years ago. Why would I do that again? What have I earned?

Karol invited me back to the shack for supper. It had a tin roof, wide gaps in the plywood walls, some chickens and dogs running around. A couple of neighborhood kids mooching snacks. One was named Dylan. He hadn’t heard of the famous singer. Max had told me that some unscrupulous characters had offered him a lot of cash to take the place.

They wanted to keep Mama in the shack, and just “borrow” the property every now and again for a little business propuesto. Too good to be true, right? Max, in typical fashion, said “The answer is always a number.”

“What did you tell them.”

“I can’t get involved in that shit.”

I go on Priceline and find Pirates Cove, a biologico on the beach, for a decent price. A collectivo takes me down the road for ten bucks. No locals have heard of it. It’s full of aggressive Qubecers. No problem. I pretend not to understand them.

The beach is rocky, so you can only really swim out at high tide. There’s a warm pool, the food is great, free coffee and juice all day, pretty chill atmosphere, except for the Qubecers, who are uniformly assholes.

Then Karol shows up with Mama, and they want lunch. So we march down the road one mile to La Tortuga, where the service staff lives up to their name. Mama orders arroz con suerte, and gets what she deserves. Karol and I have ceviche con tostones, and everyone complains they are over-cooked.

I pay for lunch, but they encourage me not to leave a tip. The road workers are camped under the palm trees sharing a working man’s lunch with lots of beer. People basically look happy, everyone waves, but the road business strikes me as fishy. And this lunch joint just sucks.

When I searched for a Priceline hotel, I found very fancy all-inclusive and adults only resorts going in around the head of Drake Bay. At about $3000 per night. In the town of Drake Bay itself, where the airstrip is located, there are very few accommodations. I was lucky to find the kind of lodging where I was comfortable.

There is reasonable suspicion, however, that a sizable resort development is taking shape that is more favorable to the picturesque sunset, and that is where all these heavy trucks are going.

We went back to the biologico, where Mama seemed to know the entire kitchen staff, and they spent a pleasant afternoon drinking coffee together on the veranda.

Karol and I lounged in the pool, the bar boy bringing us complimentary beverages of fruit flavored water on ice, all very friendly. At some point, he began serving alcoholic drinks to Karol, which to me at least seemed complimentary, a local favor. Karol did not strike me as a drinker. Yet in a short span of time, she had had four or five. She said that my Spanish got better with each of her drinks. She enjoyed practicing her English.

When the time came, the hotel staff would not accept her credit card for the bill. At first I just thought they were comping her as a local, but in fact they were denying her service precisely because she was a local. They must have thought she was with me. This struck me as very prejudicial, but I had seen versions of it before.

Rather than force the issue, I felt in that context it was expedient to settle the bill and then complain afterwards. So I had them put it on my tab and the deed was done. Karol and Mama went home, and I crashed in my air conditioned, beach side pad at last. Very comfortable. If a bit confused.

When I got back to San Jose, it seems a disturbance had broken out in La Carpio. A new group of migrants had decided to squat on some vacant land, and some of the locals became animated. Police entered the locality in force, deploying tear gas, and the locals responded by erecting barricades of burning tires.

I read about this from a safe distance in the local newspaper. It seemed pretty clear that the police were scared, and had over-reacted with disproportionate force. I don’t know if anyone was killed, but many were terrorized on both sides, especially the police.

“It’s a good thing you didn’t go to Puerto Viejo.”

“How’s that?”

“A Sargasso tide washed up on the beach, a foot thick. Rotting weed everywhere. Stinks to high heaven. The tourists in the resorts are going through the roof. How’d you like Drake?”

“Someday this war will be over….”