During the months of September, October and November in the skies near Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, an incredible natural phenomena is observed. It’s perhaps as surprising as the sighting of humpback whales or the mass arrival of turtles: the migration of birds of prey, peak occurs in the second half of October.

This story was first published in 2015.

****

Heads up! One of the most spectacular wildlife displays on the planet is happening in the skies over Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast right now: fall raptor migration. As the days grow shorter in the Northern Hemisphere, billions of migratory birds around the globe are making the annual southward journey to their wintering grounds. While many accomplish mind-boggling feats of endurance, few put on a show like raptors, which converge by the millions into what’s known as a “river of raptors.” And one of the best places in the world to witness it is the Kèköldi indigenous territory on Costa Rica’s southern Caribbean coast.

What’s a raptor?

The term “raptor” refers to birds of prey, which share a set of adaptations that allow them to hunt other animals and consume flesh: excellent binocular vision and a semi-transparent “third eyelid” to protect the eye, strong feet with sharp talons, and a sharp, hooked bill for tearing flesh. In the Americas, this group is primarily represented by hawks, eagles, kites, vultures, falcons, owls, and the osprey. And while they’re well built for high-speed attacks, for most raptors a long-distance journey of continuous flapping flight would simply be too energy-consuming. Their solution? Soar.

Riding thermals

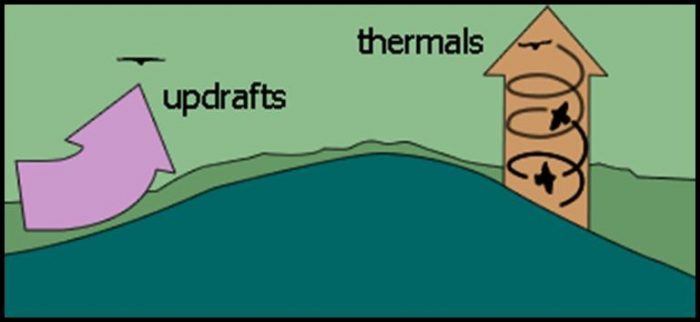

To conserve energy when migrating, raptors rely on pockets of rising air in the form of updrafts and thermals to help them gain altitude without flapping. An updraft occurs where a steady wind meets an obstacle, such as a mountain, and is forced upward. A thermal is a column of rising warm air that occurs when the ground warms unevenly in the sun; for example, the air over a field will warm faster than the air over a forest, creating a zone of rising air that a broad-winged bird can simply ride upward.

When raptors enter a thermal, they soar in tight circles, spiraling upward. As the air rises and cools, it provides less lift, and when the birds reach a certain height they peel off and glide in the direction of travel, slowly losing altitude until they (ideally) reach the bottom of another thermal, where the process begins again. Raptors are generally solitary, but ornithologists believe that travelling in large groups makes it easier to locate thermals.

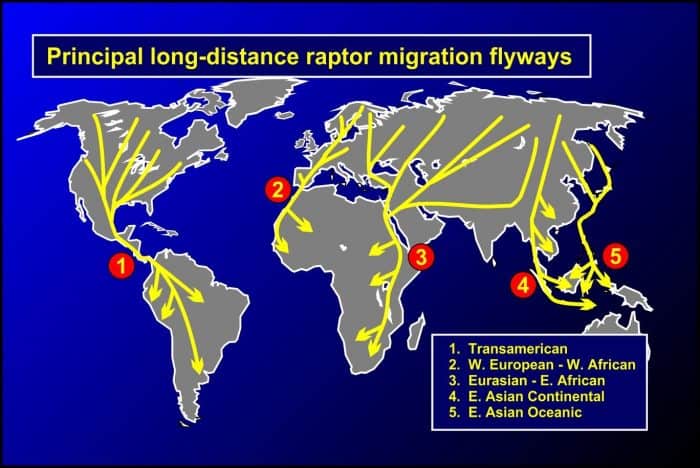

Raptors tend to migrate over level terrain, avoiding obstacles like tall mountains and large bodies of water (since thermals don’t form over water). This strategy channels them into “flyways,” where they may be able to take advantage of updrafts along the edge of a mountain range or thermals along a coastline, for example.

Migratory bottlenecks: Mexico and Central America

Where geographic features funnel migrating raptors into a bottleneck, it’s common for thousands of birds to pass by a given vantage point in a single day. Five sites (so far) in the world have been identified as “million-raptor watch sites,” places where a million or more raptors can be observed in a single migration season. In the Eastern Hemisphere, there’s Eilat, Israel and Batumi, Georgia, which see dozens of raptor species flowing from both Europe and Asia southward into eastern Africa. But for sheer numbers, the trans-American migration takes the cake.

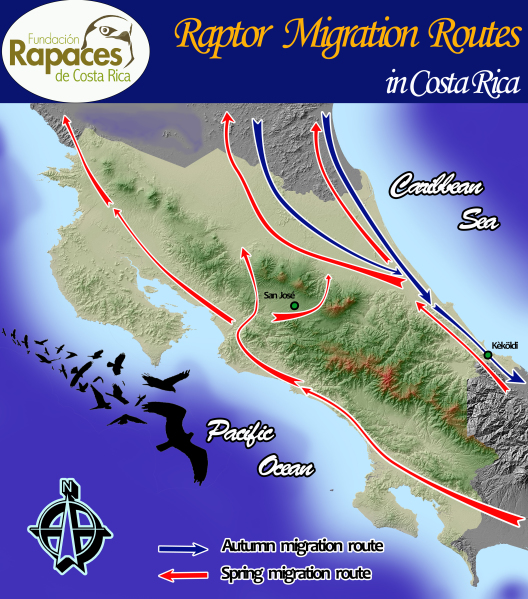

Raptors migrating from North America to Central or South America flow into Mexico across a broad front, but the mountainous terrain eventually channels them all toward the Gulf Coast. Near the port city of Veracruz, the mountains come so close to the coast that the raptors are squeezed through a passageway only a quarter of a mile (0.4 km) wide. This spot has the highest concentration of migrating raptors in the world, with fall migration counts topping 5 million.

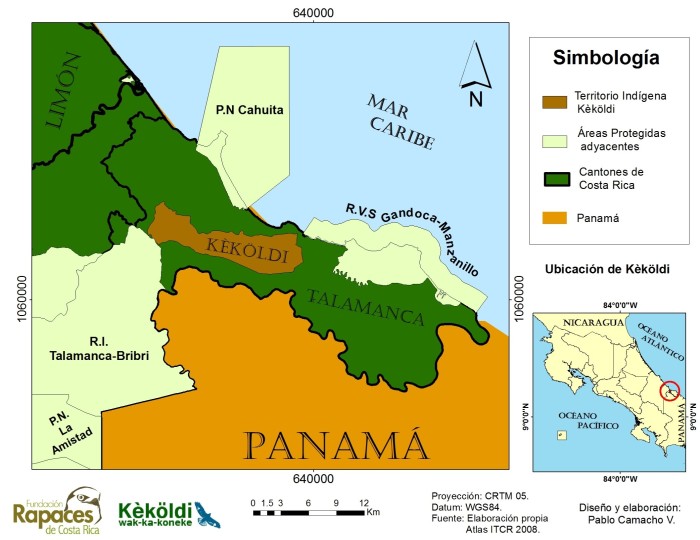

After the birds pass Veracruz, they disperse and take different routes through southern Mexico and into Central America, some “dropping out” as they find a place to stay for the winter. When they reach Costa Rica, the country’s mountain ranges funnel them once again toward the Caribbean, where eventually the broad Talamanca Mountains press so close to the coast that the birds are forced through a narrow chute just a few miles wide. The perfect vantage point for this is the Kèköldi indigenous territory, where fall raptor counts average 2.5 million per year.

The scenario repeats when the birds turn south and fly along the Panama Canal to reach the Pacific coast, crossing over Panama City, where raptor counts are held at Cerro Ancón. Fall counts reach 3 million, and just last week Audubon Panama tweeted a count of over 1.1 million raptors in a single day.

Kèköldi Scientific Center

I was lucky enough to see the migrants in action at Kèköldi in October as part of a weekend-long raptor identification and conservation course offered by the Costa Rica Raptor Foundation (Fundación Rapaces de Costa Rica, FRCR) in conjunction with the Kèköldi Wak Ka Koneke Indigenous Association.

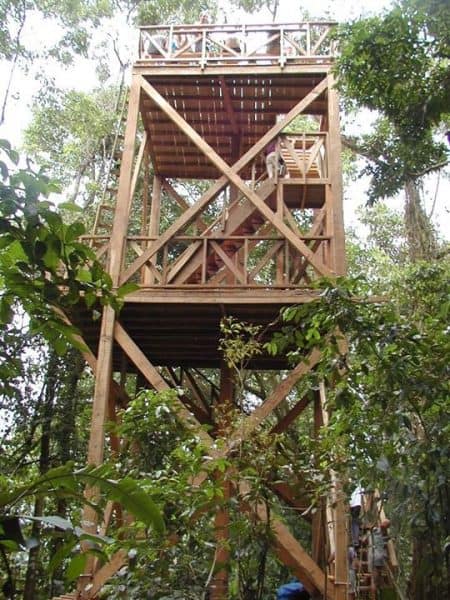

According to Sebastián Hernández Balma, president of the association, the Kèköldi indigenous territory is home to more than 300 members of the Bribrí and Cabécar indigenous groups. The Kèköldi Scientific Center, of which Hernández is director, lies in the heart of the territory and boasts a spacious, open-air lodge, an observation tower and access to several trails.

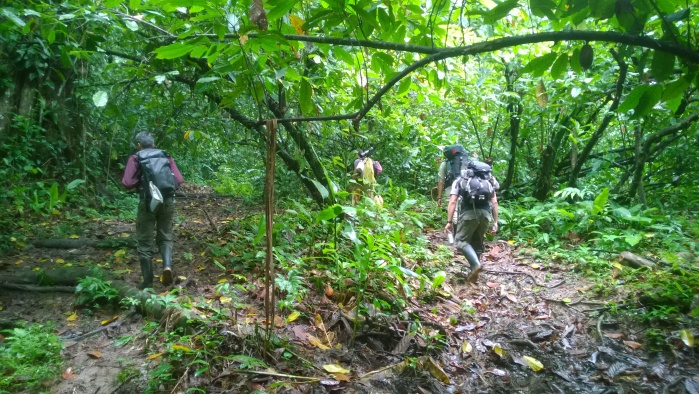

The center operates primarily as a research station, receiving researchers from around the world and a variety of fields. Since I set out for Kèköldi with nothing but soaring raptors on the brain, I was blindsided by the beauty of the place and the wildlife living, well, on the ground. (Like the 6-foot bushmaster coiled in the middle of the trail on our night hike.)

A total of 17 species of migrant raptors pass over Kèköldi each migration season, and FRCR Director Pablo Camacho led our group through a raptor identification course, focusing on the most common species for October: turkey vultures, Swainson’s hawks, broad-winged hawks, Mississippi kites, peregrine falcons, ospreys and a few others. Since it’s often impossible to see the markings on birds viewed against a bright sky, identifying them comes down to knowing small details of their silhouettes, along with size and flight behavior.

Fortunately, it didn’t rain the morning we scaled the observation tower and as the sun warmed the ground, swirls of raptors appeared on all sides, slowly rising on thermals. They were small at first – each churning ball of birds would ascend as a unit until one or two at the top would straighten their path and glide out of the group, headed southeast toward Panama. As others followed suit, the ball would dissolve into a straight line of specks and fade from view.

As the morning warmed up, larger groups appeared. One group flowed into the bottom of a thermal for so long that the thermal looked like a tornado of raptors – birds flowing into the bottom, swirling hundreds of feet up, exiting the thermal, and cruising in an organized line to the bottom of another one, while hundreds of birds continued to enter the first one.

Gazing at an endless stream of birds sliding across the sky is pretty hypnotic – until a peregrine falcon streaks overhead like a missile, and terrified parrots burst out of the trees squawking and screaming and flying for their lives. And with good reason. The peregrine falcon is the fastest animal on earth, and a fierce hunter that takes other birds easily. They’ll soar now and then, but they are usually flapping like mad, in this setting a lone speck advancing at breakneck speed through the clouds of gliding birds. According to Camacho, Kèköldi has the distinction of seeing the highest concentration of migrating peregrines in the world.

The FRCR ran raptor counts at Kèköldi for several years but, unfortunately, had to stop after 2010 due to lack of funds. In the years that the count was conducted, the highest numbers recorded were 3 million birds in a single season (fall 2010) and 450,000 birds in a single day.

It may already be November, but migration season isn’t over. Anyone who can get to the Caribbean coast in the next month should be able to spot migrating ospreys and turkey vultures spinning on thermals, and maybe even a few peregrine falcons. But good luck getting a photo.

Robin Kazmier is editor of various field guides and natural history books, and author of National Parks of Costa Rica (with photographer Greg Basco). She lives in San José. “Into the Wild” is published monthly.