GOLFITO — Reinier Aguilar Villalta never misses class.

The 41-year-old English student sits on the far left of an elementary school music classroom as he waits for his 6 p.m. English lesson to start. The broad-shouldered, brown-eyed Golfito native has a soft smile. He is currently unemployed after a work accident that broke his ankle and femur, leaving him with new pieces of metal in his body, out of work and unable to hike, his favorite pastime.

His classmates, women and men aged 17 to 64, shuffle into their desks, set up in a circle. Some are wearing school uniforms, while others dress in their work button-downs. Abraham Vallecillo, the professor, smiles as they enter, welcoming each student by name.

Eighteen years ago, the port town of Golfito made international headlines after 23-year Kansas University student Shannon Lucille Martin was murdered here. In her name, students who studied abroad with Shannon, her family and the Golfito community have set up a foundation to help the local community.

Villalta has been a part of the English-language program offered through the Shannon L. Martin Foundation for almost a year. Like many of the other students, he is taking the class to learn English for better job opportunities.

“We have a two-face,” Villalta said. He explains how Golfito is a warm, beautiful place with kind, hardworking people. Yet, the other face shows a broken economy, leading to crime and violence.

The light in the Golfito community

Daisy Sanduez Mata’s hair is tinted red and cut short. She is a 62-year old hair stylist at a local resort, Casa Roland, who wants to learn English to communicate with her grandchildren in the United States and for her work with tourists.

Marcos Mata Baltodano and Diego Reyes are the only two 17-year old students permitted in the class that normally has an entrance age of 18. This is because they are soon heading to the International Fair of Technology in Phoenix, Arizona, where they will discuss how technology can address social problems. Their project focuses on technology that helps people with hearing disabilities better communicate with others.

58-year-old Hector Ruiz Morpmiza and 59-year old Carlos Luis Solano are studying English because they wanted to learn a new language. They feel grateful for that chance.

“I feel good,” said Morpmiza, emphasizing how learning the new language has given him the opportunity to see himself in a different light, an opportunity he thanks God for.

Others in the class include young mothers, hotel and store workers. Currently there are 17 students employed at jobs where they need English skills because they work directly or indirectly with tourists.

The non-profit English program is offered Monday and Wednesday from 6 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. and is split up between beginner and advanced levels. The nine-month program not only helps students with language skills, but also strengthens community bonds as students share job opportunities, their opinions on Golfito and their lives.

Students in the classes do not pay for anything outside of their textbook, as the program is funded by donors from the United States. The foundation seeks grants and other donors in order to expand the program.

Kristin Syverson Cox studied abroad with Martin in 2000. The Shannon L. Martin Foundation was founded in 2004 through Martin’s mother, with the support of the Coast Guard Academy. When the Academy left, the foundation closed, but Cox helped re-launch it in 2014 and now heads it.

“I knew I always wanted to go back, and I know Shannon felt the same way,” said Cox, who didn’t want Golfito to be defined by what happened to Martin. “It just made sense for me to do it in honor of her and in memory or her. I felt like if she were around, she would want to do the same thing.”

When Shannon Martin was a study-abroad student in Golfito, she helped tutor about 30 children in Spanish. Jose Moya Villagra was one of those students, and he says today that the English he learned made a lasting impact on his life and career in the sportfishing industry.

From Villagra, to a baby named after Martin in 2005, to the dozens of people who are helped by the Shannon L. Martin Foundation today, it’s clear she has left a lasting impact on the community.

The Golfito Undercurrent

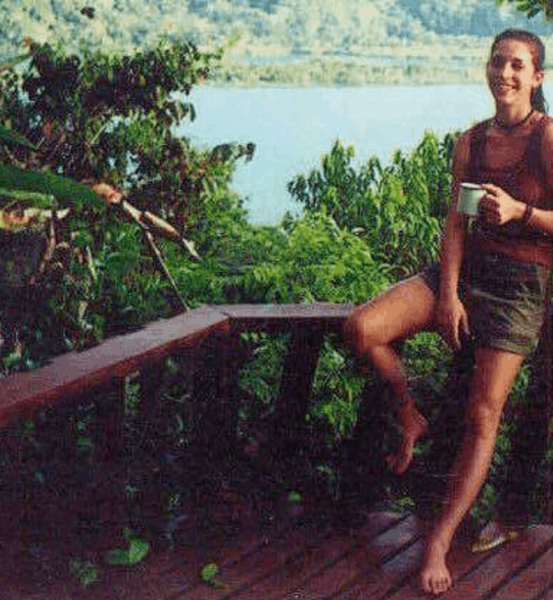

Shannon Martin spent a semester falling in love with Golfito in 2000 and hoped to one day return to days of hair thrown up in a messy bun and flip-flops under the Central American sun.

She left Costa Rica but returned to Golfito to collect fern samples she was studying. On that trip, she was murdered. It was a week before her college graduation and came as a shock to Golfito.

Reineer Villalta says he saw Martin hours before she was murdered outside her host parents’ house, feet away from the beach party he threw that May at Jurassic Bar. He recalls 200 people lining the street outside because it was packed full of people.

“The community was shocked. They couldn’t believe it. It was the worst thing that could happen. They were sick that it happened,” said Shannon’s mother, Jeanette Stauffer-Schorr.

She remembers people approaching her simply to say how much they had liked Shannon, how sorry they were.

During the investigation, Stauffer-Schorr visited Golfito at least 10 times. Since the investigation, the study abroad program in Golfito in which Martin participated has been terminated.

The increase of crime and poverty in Golfito stems in part from the state of the town after the United Fruit Company left in the 1980s, rocking the framework of the Golfito economy and then the community.

Since Golfito lost its driving economic source, it has been trying to recover. The U.S.-styled corporate houses in Golfito are now left dilapidated and abandoned with missing windows surrounding by old stalks of banana plants.

In an effort to recuperate its economy, Golfito became the home of the Depósito Libre, a tax-free warehouse, in the 1990s. But its economic impact couldn’t replace that of the United Fruit Company.

Abraham Vallecillo believes the Golfito people are dependent on the resources that were always given to them.

“There’s a bad idea that is thought by the people, that if we don’t have the United Fruit Company, we are nothing. We don’t have the Depósito Libre, we are nothing. Those are ideas and that produces something psychological that we see in a lot of people,” Vallecillo said. “People need to open their eyes and see that they are worth it, they are of value and that they can prove themselves.”

Villalta says that the biggest problem he sees in Golfito is that “we don’t know how to conform.”

“We need to find something better for us,” he adds before listing off ideas centering around the city’s biggest issues. He recommends having more resources for women in the area, a way to connect them with some sort of occupation or institution.

“The domestic violence is a lot,” Villalta explains, mentioning a case where a woman was murdered by her husband earlier that week. “The men go out in the street with their friends but the women are in the house. It’s like this cannon explosion. The pressure comes, comes, comes and then one day…”

He trails off, then transitions to ideas for students who otherwise might fall into the party or drug scenes. He says programs like the Shannon L. Martin Foundation can challenge students to find more opportunities than are currently available.

Shaping the future of Golfito

Reinier Aguilar Villalta was Shannon Martin’s close friend. They met in 2000 during Martin’s first week in Golfito. He recalls the nicknames they had for each other — “Piggie” and “Mount” — and the conversations they had about differences in culture and relationship advice with her Costa Rican boyfriend.

“She was like a sister,” Villalta said, describing Shannon as a friendly person who would stay in the street and talk to people. He says that the foundation is like she was.

“It helps the people in the town,” he said. “It is like a part of her.”

Vallecillo says he doesn’t want to dwell on what can be perceived as negative, but mentions the foundation’s story to illuminate something about Golfito he thinks is often overlooked.

“Whose mother and whose friend wants to help people or the community who stole the life of a person?” Vallecillo asks. He uses that as part of his fight in favor of Golfito. “Believe me, I will do everything I have to do to make the lives of my people better here, of my community.”

Since the United Fruit Company left, Golfito has endured economic and social struggles. The Southern Zone is Costa Rica’s poorest, and facing a lack of other opportunities, some community members turned to drugs and violence.

That violent undercurrent took Martin’s life, inspiring a foundation which aims to break the negative cycle.

“I feel like the project is working for Golfito,” said Villalta, who believes the Foundation is a good push for advancement of the public.

Using the skills he has learned at the Shannon L. Martin Foundation, Villalta plans to move to Heredia to open a hiking and athletic store. He then hopes to return to Golfito to open a business there.

“I see a good future for Golfito with the tourists,” he said. “We want to open a store here, like sport shoes and sportswear.”

Meanwhile, Villalta still doesn’t plan to miss class.

“I told Abraham I would come back here one day per month for class, then the other days I will video call,” he says, smiling.

Click here to learn more about the Shannon L. Martin Foundation.

This article was sponsored by the Costa Rica USA Foundation (CRUSA). The Tico Times Costa Rica Changemakers section is a sponsored partnership between The Tico Times and CRUSA.