Is it possible for humanity to live sustainably with nature and technology?

Daan Roosegaarde, a young artist, innovator and architect from the Netherlands, and with his group of designers and engineers, are on a quest to answer that question – and to create what they call the Landscapes of the Future. His projects include the Smog Free Project, Van Gogh Path, Waterlicht and Windlicht, which address issues such as water and air pollution, and producing clean energy.

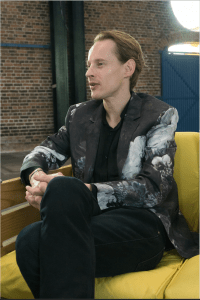

Roosegaarde, 37, studied art at the Institute for the Arts in Arnhem and the Academy of Fine Arts in Enschede. He then obtained a master’s degree in architecture at the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam. In 2007 he founded Studio Roosegaarde in the Netherlands and later opened offices in Shanghai, China. In 2016 he was named one of the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Leaders; and Artist of the Year in the Netherlands; and a Creative Changemaker by Forbes and Good 100. In addition to multiple design awards, he has given lectures at TED and international mass media such as The New York Times, CNN, Bloomberg, Wired, Artsy, China Daily, Impactmania and Dezeen have written about his marvelous work creating a better world for the future.

During the seventh International Design Festival’s (FID) at the Antigua Aduana in San José, Roosegaarde spoke about how humanity must cope with these new challenges we’re facing in order to create a sustainable world.

Roosegaarde granted The Tico Times a special interview during his visit. As we strolled through the Antigua Aduana’s plaza, Roosegaarde spoke with us about his life and work. Excerpts follow.

Why did you choose to become an artist and an innovator?

You don’t choose to be an artist. It just sort of happens. I think it was always this desire to make myself more connected to the world that was around me. I grew up in these hard concrete houses, and it always felt so sterile and static. I always wanted to make it more interactive, more personal and more open. That’s when I started to use technology in order to make it happen.

How did you discover that you were interested in the relationship between nature, technology and humanity?

I live in the Netherlands, below sea level, so everything that you see is planted. The whole country already has this relationship between nature and technology: without it, we wouldn’t survive and exist. For me, [nature and technology] have a lot of similarities, the growth, the evolution, the trial and error, but somehow, we don’t see it like that. Technology is functional and nature is something you go on a Sunday to look at: you go to the forest. I wanted to create a more natural experience.

When you decided to become an architect, what type of buildings did you want to design?

I just started to look a lot at architecture. I took the train and went to all the beautiful old-school buildings, from Ponte Old in Rome to more modern architecture to the Japanese architects in Tokyo, and that helped me a lot to think. Then I started to make this more interactive art and architecture and we started to connect it with more social topics like clean air, clean water, and clean energy.

Afterwards, the scale became much bigger. That’s where we are right now. In a way I’m coming back to architecture, and that’s really good.

How do you create a concept that balances art, technology and humanity?

I don’t think of these kinds of divisions. You try to make proposals for the future, what you want the future to look like. You don’t want to think in terms of opinions; you want to work on proposals. Some projects are a bit more practical, like Smog Free, and some are more poetic, like the Waterlicht with the blue light. It depends on the context or my personal obsession. It depends on what I think is really important at that moment.

What is your research process?

If you make something, it’s like a taste in your mouth [makes gesture of touching his tongue with one of his hands]. You don’t know the ingredients. You start to read, to write, to travel, to experiment, and it’s the same way when you make a pancake. The first pancake always fails. You make mistakes, and in the end you have your top chef cook a star dessert that you can share. It’s a lot of trying and shooting and experimenting.

Sometimes people ask us a question, like a mayor from a city, a government, a private collector or an airport, but sometimes we commission ourselves. For example, for the Smog Free Project, there was no request. We spent our own time imagining it, and now everybody wants it. At the beginning no one wanted it.

Which has been the response of politicians and governments to the Smog Free Project?

In the beginning they were very risk-averse, so they had a lot of questions because it was something new. Since the successful launch in Beijing, we’ve had serious talks with India, Kazakhstan, Paris, and London. At the beginning it was not the case.

What plans have you made with all these countries and cities you mentioned?

It’s going to be a Smog Free campaign. It’s not just a tower, but also Smog Free bicycles, a Smog Free symposium and a workshop with students, so it will be a series of events for the upcoming three to five years.

What was the process to create the Waterlicht and the Van Gogh Path?

It was actually a request from the Dutch Water Board. We were playing with several ideas to create water. In [mid] process we had to [come up with an idea] to visualize it and we did some tests and it really worked. While we were testing, people were walking by and they were like: “Holy shit, the dike is breaking. We’re being flooded.” We never imagined that it would become so popular in that way. It became a really mesmerizing experience for many, and a beautiful scene. The government was really happy because finally people were starting to realize the work they were doing. Before, everyone took it for granted.

The Van Gogh Foundation came to us to celebrate Van Gogh’s 125th [birthday] and it was specific for the spot where he lived and worked from 1883 to 1885. They came to me and said: “Can you make something to make the area more alive?” We got to work and I wanted to do something practical, poetic, with lights. We did that quite fast. I think we did it in ten months.

What technologies have you developed through these projects?

I think with every project we develop new technology. Sometimes it was an optimization that was already there. Sometimes it was something completely, new and you always work with a team of designers and external experts to make it happen and make sure that it works and remains working. That’s also very important.

What’s the most complex project that you’ve done?

I think the Windlicht was very difficult to do. Although it looked really simple, it was really complex, and the Smog Free as well. The Waterlicht was actually quite easy because you don’t need that much material and nature does most of it. The wind and the humidity bring it to life because the wind always changes, even in the same evening. It keeps changing because nature changes. We got a lot of gifts from nature there.

In the end, it doesn’t matter because it’s about the interaction you have with the audience. They don’t care if it was difficult or easy [to make].

Regarding nature, how do you make sure that everything goes well when projecting your work?

You do a lot of tests and prototypes, indoors and outdoors, as well as simulations in the computer. You know that when you start with an idea it can completely change. It grows. Every project fails somewhere, but in the end we always manage. That’s part of the project.

Since the Windlicht was the most difficult one, how did you manage to do the rays of light?

You had to match the two floating points. The windmill was moving and the blades were moving, so you have to sort of create a stable connection and it was quite difficult.

How do you measure the exact points were everything meets?

You have a series of sensors, tracking software and cameras, and they feed the software. The software calibrates how they send the lights, but it has to be very precise because if you miss a blade, the line just keeps on going. You first send a test signal with lights, the light reflects and it’s all in a millisecond. Once you received that signal, then you send the visual light.

How does your work combine math, nature, science, and art?

I think the world is about making new connections, so you can never solve a problem if you only look at it one way. I always need to make things that trigger diversity.

[Through culture and art] is the only way [to improve the world] because it’s not working the way that it is right now. We should come up with new proposals and that’s a design challenge. You can show how it can be done differently and you show the beauty of it in the hope that people accept it fast, so you can progress.

In your lecture here you mentioned the fear that we as humans have of technology. How can we overcome it or create a balance with it?

I think technology is a great tool. Right now we’re sitting in front of a computer screen feeding our hopes, dreams, and fears to Facebook and Twitter, and that’s sort of weird. The machines should help us, and the machines that we have are killing us, like the cities and the cars. How can we learn to use it to our own advantage?

You have to learn to approach it differently. For example, it can be used to make cities clean again, promote cycling and all of these kinds of things. I like to use it this way.

Regarding these new technologies and topics, how do you think Costa Rica is doing?

I think it’s weird when you look at the city we’re in right now. There’s a real separation between city and nature, so we don’t learn from nature in that way, to make our city more energy friendly or more human. There’s no real connection, in a way. I think that a good city would try to integrate them much more… and clean water, clean energy, clean air.

How can we start to implement these new technologies in Costa Rica?

It starts with something very simple. Start putting the layers of solar panels anywhere you can find. That’s a low-hanging fruit. It’s a simple step. You need to be ambitious. You have the [2021] carbon neutral target, which you’re not going to make, but it’s good to have this sort of great ambitions and at the same time trigger the minds of the young people here so that they also begin to think in the new ideas for proposals.

Since we’re not going to make the carbon-neutral goal, how can we reorganize?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s something we decide in a conference like this together. What we want, what we think is feasible. Don’t wait for the government to make the decision. It’s up to you.

Finally, what inspires and motivates you to continue working with these innovative ideas for the improvement of the world?

I think you’re always a voluntary prisoner of your own imagination. You look around and wonder, why are we always doing it like this? Why can’t we do it like that? So it sort of starts out of this irritation or wonder. Then you start to create.

If it goes right, sometimes you need to learn and start over again, but it’s fascinating to take hold of the world around you and see what happens. To see what works and what doesn’t work.