I didn’t even have to ask my wife why she was cursing. The swells tossing the boat were making me a little queasy too, and I don’t get seasick.

“You forgot your pills?” I asked.

“Yep,” she replied, pressing out her chin, the way she always does when she’s upset. “Normally, I have some in the first aid kit, but I already checked.”

I thought of ripping through the snorkel equipment for the first aid kit so I could double-check, but I needed to hold on to something. The best spot is upstairs, said Mike, our guide, when we boarded. He didn’t factor in the swells of the Pacific in April, nor Cristina’s tendency for motion sickness.

“You’ll be fine,” I told her, attempting to rub her shoulder. The buildup of sand glued by sunblock to her skin kept me from continuing.

“Once I get in the water,” she replied, nodding.

That would be a whole other battle: the water. We were on our way to Catalina Island, off the coast of Guanacaste. It would be two hours to the island after we’d stopped to let the resort divers take their open water dive. We were not going to scuba dive. We were onboard to Snuba dive.

Snuba is the love child of snorkeling and scuba diving. Whereas in scuba you strap a tank to your back, and in snorkeling you hold your breath to dive, in Snuba you’re attached to a 20-foot hose. That hose connects to a small raft holding an air tank for you and your partner. It’s the same tank used in scuba, as is the regulator at the end of the hose.

To kill two birds with one stone, I’d dragged my friend Kavi out onto the boat with us. He had arrived only the day before for a brief Costa Rican vacation, in a lovely shade of alabaster.

“Everything okay over there?” Kavi asked, leaning from his side of the craft.

“Motion sickness,” I replied, shaking my head as I pointed at Cristina.

“I have sunblock,” he replied, shrugging.

“Thanks,” Cristina replied. “I don’t think it’s sun poisoning.”

Kavi proceeded to slather sunblock on his already lobstered shoulders like it could unburn his skin somehow. I guess I didn’t consider the fragility of my adventure pals before planning this excursion.

“I normally get a base coat before travels,” he said. “Been too busy to tan.”

“Keep applying,” I replied.

“There are three very simple rules,” were the first words Mike said at the boathouse before we left. He had pulled the six Snuba divers into a little circle. I expected a revised “Fight Club” set of rules, but this was no time for jokes. Mike, whom I know to be a fun-loving guy, went into super-professional mode. It was comforting. “Number one, relax…”

He demonstrated what relax looked like, leaning back with his arms clasped in front of him, then listed two more rules, something about breathing and not taking out the regulator. I didn’t need to record this information, as I’m a certified scuba diver. This Snuba business would be a walk in the park.

I hadn’t considered the Cristina factor.

“I can’t mouth-breathe,” Cristina interrupted.

“You snorkel, right?” Mike replied. “How do you do that?”

He was right. I’d let Cristina convince me that she couldn’t mouth-breathe, but there’s no way that could be true. The snorkel mask covers your nose, so she could hardly be nose-breathing while snorkeling. She could do it. She just didn’t know she could.

The stunned look on Cristina’s face was followed by a delayed “Right.”

When we finally got to Catalina, I knew Cristina would be fine for the most part once she got in. Before we jumped in I pulled her aside.

“Take a minute to look around underwater once you get in,” I said. “It’s a whole different world. You need to acclimate to it before you try doing anything.”

“OK,” she replied, the concern jamming together between her eyebrows.

I’ve been underwater in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, off the coast of California’s Santa Catalina Island (apparently it’s a popular name for islands), and all up and down Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. Every time, whether snorkel or scuba, I’ve always needed a moment to acclimate underwater.

On my first scuba dive in the Caribbean, I used up half my tank before the divemaster was able to calm me down. We were on the floor of the ocean, in nature’s aquarium, where I was confident my oxygen was out or blocked. The divemaster opened up my valve full blast, then made eye contact with me.

She made a slow, deliberate back-and-forth motion with her hand, instructing me to breathe with her until I calmed down. Only later did I understand I was suffering a panic attack. There was nothing wrong with my regulator. Since that time I always take a moment to acclimate.

Five feet down, sinking naturally, I stopped my descent to find Cristina behind me. The panic in her eyes was unmistakable. She was struggling to accept the whole underwater breathing phenomenon, which is admittedly weird. There is no talking. I couldn’t tell her to take it easy, so I repositioned to face her, pointing two fingers at my eyes, then at hers. Two petrified eyes obediently fixed on mine.

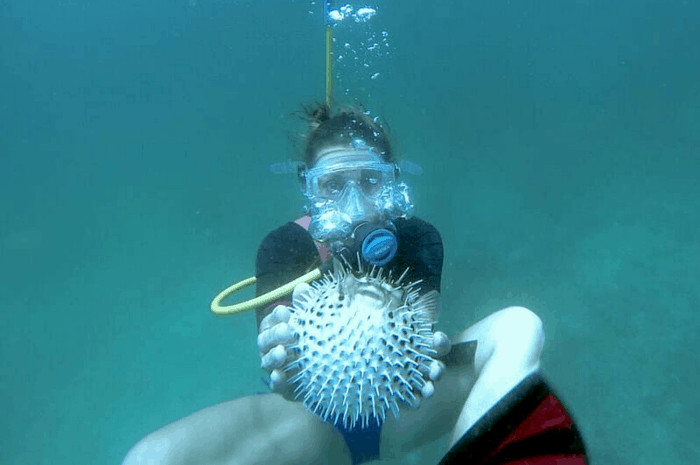

Then I started making the back-and-forth motion with my hand, which took her a second to understand, but she nailed it. After 30 seconds, her eyes went from chihuahua to sloth. As we descended together she made a clapping motion with her hands. Moments later, Mike was handing her a pufferfish blown up like a, well, a pufferfish. We even took pufferfish selfies.

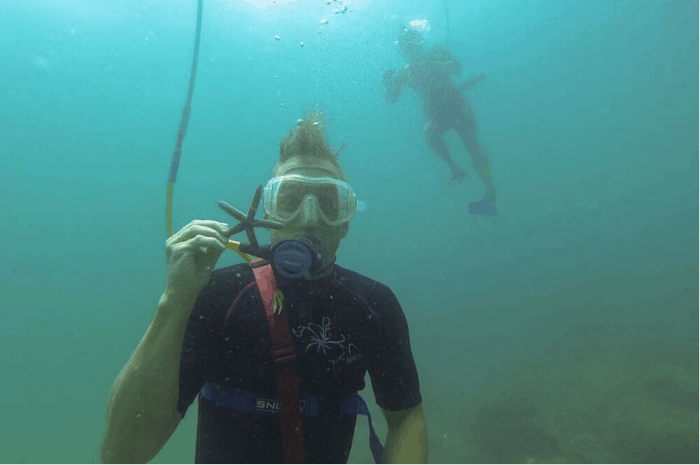

In all the excitement I forgot about my albino friend, Kavi. Thankfully, he was easy to spot. He was on another tank, with another partner diving up and down like a pro. In fact, the whole group was doing great.

In addition to the puffer, on that first dive we saw a moray eel, what I think was a tiger eel, starfish and many schools of fish, too many to name. With some of the creatures we were fortunate to get close enough to handle them with care, but we let Mike be our guide on this. Most dive outfits prefer you don’t touch. Because Mike knew my background as a scuba diver he allowed us to play loose, but I would recommend you don’t take those liberties if you go.

By the second dive, Cristina was a pro. In fact, if she hadn’t pointed out the manta ray floating like a throw rug along the ocean floor, I would have never seen it. Later we would find out we were the only two who saw it.

“You all did so well,” Mike said to us finally back at the boathouse. Then he turned to me, quietly saying, “Good job with Cristina.”

Cristina nodded in agreement.

“You saw that?” I asked.

“It allowed me to focus on everybody else.”

This is the illusion of ecotourism in Costa Rica. It’s like going to your local amusement park, minus the cotton candy. You consummate the illusion of danger with very little actual risk. By the numbers, you’re at greater danger in your morning commute than we were chasing eels. The thrill is, it doesn’t seem like that. At the end of the tour, you feel like Hannibal after crossing the Alps, minus the snow and bloodshed. You feel like a hero.

IF YOU GO

What to bring: Swimwear, sunscreen, sense of adventure.