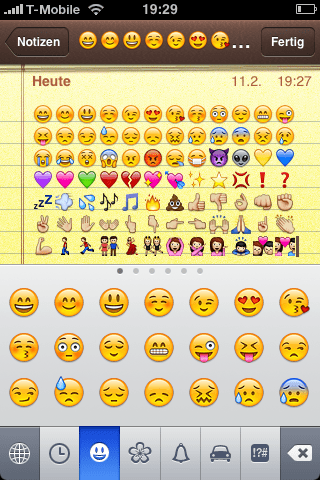

While many of us tap out these symbols to our family and friends, there are no universal usage rules for emoji: no grammar, no meanings. No syntax.

But Fred Benenson, the visionary who gave you “Emoji Dick,” is trying to change all that. In fact, Fred Benenson is trying to turn emoji into a bona fide language.

“Emoji are now an essential component of how we’re talking to each other,” Benenson said. “And experimenting with them gets us to a better understanding of what they actually mean to us and how we can use them.”

On Kickstarter, the platform where Benenson first launched his “Moby Dick” translation — and where he now works, as the site’s data lead — the unlikely linguistic visionary is raising funds for an online tool that could translate even complex English sentences into emoji.

Unlike other efforts in this vein, Benenson’s “Emoji Translation Project” won’t just match keywords to their equivalent symbols and sub the symbols in. Instead, it will work much like Google’s high-powered translation engine: first gathering texts in English and emoji, produced by human translators; then running those texts through a machine-learning algorithm, which searches the two data sets for patterns; then waiting and watching as the algorithm spits out a synthesized, codified grammar.

Or … not.

“It’s ridiculous,” said Arika Okrent, a linguist and the author of the 2009 book “In the Land of Invented Languages.” “Emoji are fun. I like emoji. But they’re not a language — they’re a game of charades.”

Okrent, it’s worth noting, is not someone you’d expect to be skeptical about made-up tongues: She actually speaks Klingon.

But Klingon — the fictional language of an alien warrior species, for the non-Trekkies in the audience — was set down with both rules and a writing system from its beginning. Emoji, Okrent says, are fundamentally different: Even as people begin using them to express complex ideas or full sentences, they’re using them in arbitrary, individual ways. We haven’t agreed on the meaning for the “prayer hands” emoji — forget the intricacies of expressing abstract thoughts or the present perfect tense.

That variance, Okrent says, will make machine learning impossible. (“In order for the algorithm to discover a pattern, there has to be a pattern to discover,” she explains.)

And that’s not the only obstacle Benenson and his vision face: There are literally no other image-based languages.

The last real push to invent one ended semi-tragically. A concentration camp survivor named Charles Bliss attempted to launch a universal, pictorial language, called Blissymbolics, because he believed it would decrease intercultural misunderstandings. Blissymbolics’ basic pictures are, indeed, pretty easy to figure out, which has made them popular among a small set of language therapists. But as you try to express more complex ideas, the language gets less intuitive and more confusing. Ultimately, it never caught on — a great disappointment to Bliss.

Of course, there’s a momentum around emoji that there never was around Blissymbols. An emoji — the humble — was named 2014’s “word” of the year. Instagram recently enabled emoji hashtags, a nod to some kind of mainstream desire to use the symbols instead of words.

According to Emojitracker, a tool the logs each emoji tweeted out on Twitter, emoji use has risen more than 50 percent since December 2013, from roughly 11 million tweeted emoji per day to almost 17 million now.

“I think as we use them more and more, a certain emoji lingua will emerge,” Benenson said, “and that’s what we’re interested in capturing with this project.”

Benenson isn’t naive to the challenges of the project: He knows he’ll need a huge team of English-to-emoji translators to get enough material to run past an algorithm. (Currently, he’s fundraising $15,000 to pay these translators: at 5 cents a translation, that’s enough for roughly 300,000 lines of text.) Even then, he admits, the translator might not work: There will be words or sentences it gets wrong. There will be gobbledigook.

Still, if “Emoji Dick” taught Benenson anything, it’s that there’s value in probing emoji and their cultural applications. That project was met with derision when he launched it in 2009; six years later, the Library of Congress has a copy — and emoji translations of half a dozen other books are now available online.

Benenson thinks his Emoji Translator could be put to similar use, translating books or other texts. He also envisions an API that would let other Web sites and apps integrate emoji translation.

If nothing else, he said, “we have faith that the results will be at least funny.”

It’s not a linguistic revolution — but it is something.

© 2015, The Washington Post