With its publication in the official government newspaper La Gaceta, Costa Rica’s dog-fighting ban went into effect last week. The new law clarifies dog fighting as a criminal offense and imposes stricter penalties on those caught organizing fighting rings.

Now, with stricter restrictions on the books, animal rights activists have shifted their focus on passage of an updated animal mistreatment bill that would beef up Costa Rica’s current animal cruelty laws, which activists say do little to help animals.

“Right now we have a law without any teeth,” said Adriana Barrantes, a spokeswoman for the Association for the Well-Being and Protection of Animals (ABAA), during a presentation at the Legislative Assembly on Tuesday. “We are lacking the tools to actually combat animal cruelty.”

Costa Rica decriminalized animal cruelty in 2002 after the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court ruled that the law was too rigid to enforce fairly. Animal advocates say the now nebulous laws make prosecuting animal cruelty difficult. When the state does manage to prosecute an offender, the person is usually hit with a small fine.

In the last few years a movement has grown around strengthening animal cruelty legislation. Starting in 2009, animal rights groups began protesting for stricter laws with the March against the Mistreatment of Animals. Some 600 people showed up to demonstrate.

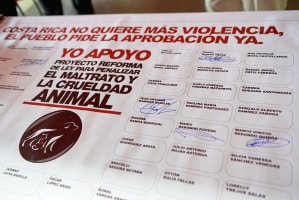

Then, in October 2011, lawmakers drafted Bill 18298 with the support of 136 different civil organizations.

Several months later an even stricter bill arrived in the Assembly by popular initiative, with 200,000 signatures from Costa Ricans. By May of this year, the now annual March against the Mistreatment of Animals had grown into a massive protest with up to 30,000 people supporting the cause.

ABAA and other animal rights groups hope that lawmakers will merge the two bills before they are sent for debate. In addition to criminalizing animal cruelty and imposing stricter penalties on violators, either bill would place sanctions on animal testing and meat operations that do not adhere to Costa Rica’s current regulations.

Most of the regulations laid out in both bills have met little opposition, but the popular initiative bill’s ban on bullfighting has stirred up controversey.

Non-lethal bullfighting and riding are traditional parts of annual festivals hosted in most Costa Rican towns. Costa Rica never developed a tradition for killing bulls, and events consist of bull riding and Tico-style bullfights where participants get into the ring and attempt to avoid getting gored. Opponents of the bill say banning the taurine events is an affront to Costa Rican tradition.

Though the popular initiative bill would ban bullfights in any form, the bill drafted by lawmakers, Bill 18298, would simply regulate them. Bullfighting approved and regulated by the National Festivals Commission — town festivals, for example — would still be permitted, while organizers of unregulated bullfights would face strict penalties.

“Our goal isn’t to take away the Costa Rican tradition, but to stop attempts to import the bull-killing traditions from Spain and Mexico and certain inhumane rodeo practices from the U.S.,” Barrantes said. “In the end we want to regulate it, rather than prohibit it.”

Newly inaugurated President Luis Guillermo Solís has come out strongly in favor of a change to the law. Increasing animal well-being was one of Solís’ top priorities during his campaign, and he mentioned the issue in both his acceptance and inauguration speeches. The bill’s sponsor, Franklin Corella, comes from Solís’ own Citizen Action Party, PAC, but the lawmaker will need to make difficult cross-party alliances to get it passed.

“PAC and other political parties have already demonstrated their support for the law,” Corella said. “Right now we need to take advantage of the agreements we have made with other parties on other bills to make sure we get this passed quickly.”

Though the bill has broad support, Barrantes and other activists worry its comprehensiveness will garner enemies in the Assembly.

“Before, the law didn’t really affect anyone. The new law would actually punish people, and that has some people concerned,” Barrantes said. “But really what makes sense is to have a law that actually does what it is supposed to.”