Twenty years have produced conspiracy theories, accusations of both CIA and Sandinista involvement, and links to the Iran-Contra scandal. Twenty years have produced multimillion-dollar lawsuits, several books, and lives dedicated to seeking the truth. But the two decades since the May 30, 1984, bombing of an anti-Sandinista headquarters in La Penca, Nicaragua, during a press conference that left four dead, including Tico Times reporter Linda Frazier and two Costa Rican journalists, have produced few answers.

THE Costa Rican government doesn’t expect those answers any time soon. Attorney General Francisco Dall’Anese said earlier this year in a letter to the Ombudsman’s Office that the investigation of the bombing at La Penca is at a dead stop, primarily because of blocked access to documents declared secret by the United States. Dall’Anese said failure to extradite former CIA collaborators John Hull and Cuban-American Felipe Vidal from the United States also has impeded the investigation.

Although murder charges were provisionally filed against Hull and Vidal regarding the attack in 1990, no one has ever been convicted for the bombing. Prosecutor Paula Guido, who took over the case three years ago, said she will not wait for the declassification of U.S. Senate documents, which could take years.

She told The Tico Times this week that she has begun writing a case to be presented by the Prosecutor’s Office before an appropriate judge. Beyond the implication of Hull, a longtime resident of Costa Rica’s Northern Zone, Guido gave no indication as to what the conclusion of her office will be in the case. But if it is anything like other investigations of the La Penca tragedy, it will not be a simple one.

SOME believe that if it was not the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) behind the La Penca attack, it had to be the left-wing Sandinista government in power in Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990. But more and more people are coming to the bizarre conclusion that both organizations – who can only be described as enemies during Nicaragua’s war-torn 1980s – were involved.

“The more indications there are, the more there is the real sense of a lack of resolution, and the trail points to both the CIA and the Sandinistas. My guess is it involved both sides,” said U.S. journalist Martha Honey, who conducted an 18-month investigation of the bombing with her husband Tony Avirgan, who was injured at La Penca while working as a cameraman for ABC.

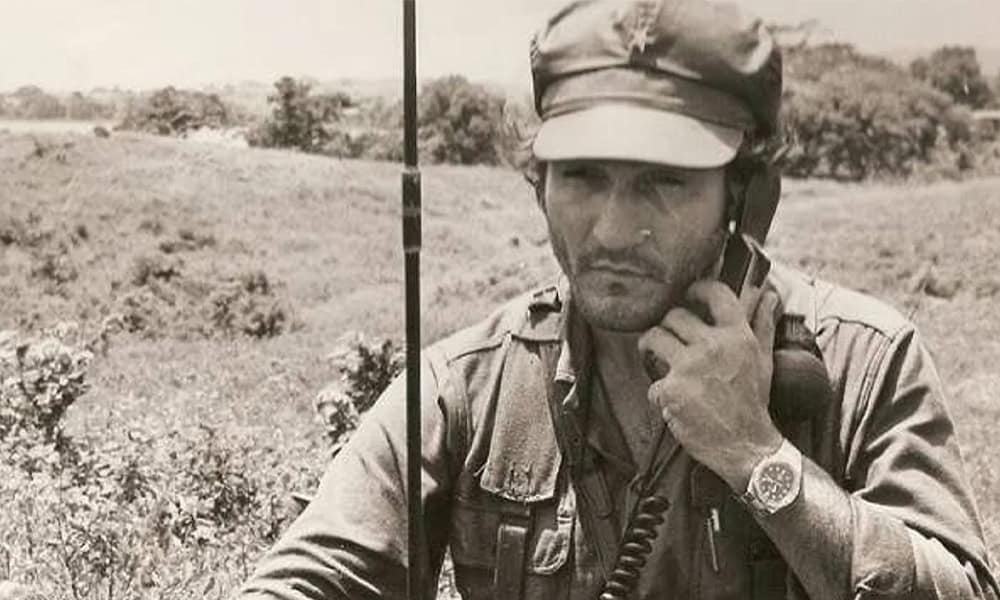

THE bombing was widely considered an assassination attempt against Nicaraguan rebel leader Edén Pastora, who called the press conference at La Penca, a remote jungle camp on the bank of the San Juan River. Pastora – the charismatic Sandinista-turned-rebel who as “Comandante Cero” led the takeover of Managua’s National Palace during the uprising against Anastasio Somoza – was not short on enemies.

When he invited reporters to his remote headquarters, he was expected to announce his refusal to join U.S.-backed Contra groups to the north. Despite CIA threats he would lose its support otherwise, Pastora refused to join the more conservative northern forces, which he said were composed of mostly former Somoza guardsmen.

PASTORA told The Tico Times this week he believes the CIA and Sandinistas were both involved in the assassination plot. Both sides needed him out of the picture in order to implement a treaty to end the war secretly negotiated in Manzanillo, Mexico, earlier that year. “It was a cross of interests,” he said.

“The Frente (Sandinista) and a right-wing sector of the United States wanted to kill me. The Frente supplied the manpower and the CIA supplied the technology.” While this may seem like an odd collaboration, Pastora explained, “The Gringos do not have enemies or friends, they only have interests.”

INVESTIGATIONS of La Penca have also been clouded by interests, according to John McPhaul, managing editor of The Tico Times during the 1980s and early 1990s. “La Penca really seemed to have a double dimension,” he said. “There was La Penca the despicable crime and terrorist act, and La Penca the political sideshow … At times during the course of the La Penca investigation many seemed more interested in pinning the crime on one side or the other (the Sandinistas or the CIA) than in bringing the facts to light and letting them speak for themselves.”

AN investigation by The Miami Herald in the early 1990s revealed the identity of the bomber, and pointed the case toward Sandinista responsibility. Reporter Juan Tamayo revealed that the bomber, who posed as a photojournalist and carried the stolen passport of a Dane named Per Anker Hansen, was a Sandinista sympathizer named Vital Roberto Gaguine. Gaguine was part of an Argentine guerrilla group based in Nicaragua that worked for Sandinista intelligence, according to Tamayo’s report. Fingerprints tied Gaguine to “Hansen” documents. Gaguine’s brother and father also identified him as the person in photos of “Hansen” taken the day of the bombing. Gaguine was reportedly killed in a 1989 attack on an Argentine military base.

Tamayo maintains that his investigation reveals that the bombing was entirely the responsibility of the Sandinistas. However, like so many conclusions in the La Penca case, there are questions. “About the real identity of Per Anker Hansen, I still have some doubts,” Guido said. “I must finish the review of the case to confirm one thing or another 100%.”

REPORTS by other journalists and investigators have pointed the investigation in the other direction. In 1990, then-Costa Rican Prosecutor Jorge Chavarría supported findings by Honey and Avirgan that La Penca was masterminded by Nicaraguan Contras, Cuban-Americans, Costa Ricans and CIA collaborators with links to international drug-traffickers, including former Panamanian strongman Gen. Manuel Noriega (TT, Jan. 12, 1990).

Following recommendations by Chavarría, San José’s Fourth Court of Instruction “provisionally” charged Hull and Vidal with aggravated murder (TT, March 23, 1990). However, extradition attempts were unsuccessful. Hull was also suspected of using a landing strip on his Northern Zone ranch for drug trafficking. These charges were eventually dropped (TT, July 28, 1989).

THE findings of the Honey-Avirgan investigation inspired not only Chavarría’s report, but also a series of lawsuits. Hull filed a libel suit against the couple in the mid-1980s, which they beat (TT, May 30, 1986). The couple responded with a $23 million lawsuit against Hull, Vidal, and more than 20 others. The suit was rejected twice and a judge ordered the couple to pay the defendants $1.3 million in attorney’s fees. In May 1999, former foreign press correspondent Roberto Cruz, also injured in the bombing (see separate story), filed a criminal case with the Costa Rican court system. He alleged the CIA masterminded the plot to kill Pastora and foreign press and frame the Sandinistas, which would justify U.S. military intervention (TT, June 8, 2001).

WHILE the U.S. Embassy in San José this week again denied any U.S. involvement in La Penca, the U.S. government is suspicious as much for what it has done as for what it has not, said Joe Frazier, husband of victim Linda Frazier. With the exception of Senate Iran-Contra hearings, most of what is known by the public about La Penca has come through journalistic investigations and independently filed court cases. “I don’t think the United States has done anything at all to attempt to find out what happened. Under the administration at the time, it couldn’t have cared less,” said Frazier, a veteran Associated Press correspondent now living in Oregon.

Frazier said his suspicion of U.S. involvement has grown over the years. “I was talking to a former (U.S.) ambassador to Honduras and we were discussing (La Penca) and he asked, ‘Do you think we did it?’ and I said, ‘I think you certainly knew about it, and probably signed off on it,’ and he was silent, didn’t say a word,” Frazier continued.

IMMEDIATELY following the bombing, the U.S. government not only failed to send help for the victims – several of whom were U.S. citizens – and failed to investigate the attack, but attempted to derail journalists’ investigations with false leads. Efforts by The Tico Times and other media to involve the FBI in the investigation were rebuffed, both in Washington D.C. and San José. “Within hours of the bombing, reports came out of Washington that it was a Basque separatist, but we found out he was in jail, when that fell apart, they put out another story, there were a dozen false reports, but they never really nailed it to the Sandinistas,” Honey said in a phone interview this week from Maryland. “If it was the Sandinistas, why didn’t the United States seize the opportunity to denounce the revolutionary government?” Honey asked.

ALTHOUGH the Costa Rican legislature in 1990 appointed a four-member commission to investigate the bombing, the Tico government has also been criticized for lack of action. “After so many years, there are no answers, only a shameful silence,” said Raúl Silesky, president of the Costa Rican Journalist’s Association, in a statement.

Robert Rivard, Newsweek magazine’s Central American bureau chief at the time of the bombing, told The Tico Times this week, “La Penca was an unjustifiable act of terror, and there is blame enough for all the region’s players to bear: the Sandinistas and the U.S. intelligence community, each of whom believed their ends justified the means; Edén Pastora, a weekend revolutionary propped up by the Reagan Administration, who saw to his own evacuation from the jungle while Linda Frazier was left behind to bleed to death; and even Costa Rica, which turned a blind eye to so much covert activity on its own soil.”

McPhaul said this week in an e-mail from Puerto Rico, “A Costa Rican judge recently told me that in the past 20 years the competence of the cops and judiciary in Costa Rica has much improved, and that if it happened today, authorities could solve a La Penca-like crime. I hope for Costa Rica’s sake that that’s true, because the lingering doubts of the kind produced by La Penca, and the recriminations they engender, is poison to the country’s body politic.”

(Tico Times staffers Jennifer Avilla, Steven J. Barry, Robert Goodier, Rebecca Kimitch, Auriana Koutnik and Tim Rogers contributed to this report.)

What Happened that Day?

WHEN reporters arrived at the remote Nicaraguan rebel camp La Penca on May 30, 1984, it was already late. Leader Edén Pastora said the press conference they had come for was to be held the next morning. But shortly after the 24 journalists disembarked from the boats they had taken up the San Juan River to the jungle camp and entered the rustic stilt house, they found themselves clustered around Pastora (TT, June 8, 1984).

And that is when it happened. At 7:20 p.m., as people were pushing forward and snapping pictures, the bomb went off. The force of the blast instantly killed Rosa Alvarez, a young radio operator for Pastora’s rebel group, and caused injuries among every journalist present, from minor to fatal.

TICO Times reporter Linda Frazier, 38, did not die from her injuries until the next morning, after a night of agony at the site. Channel 6 cameraman Jorge Quirós, 24, also died at the site. The station’s assistant Evelio Sequeira, 43, died a week later.

Meanwhile, witnesses reported seeing the person later identified as the bomber in the lower area, under the building from where he had used a remote detonator to set off the suitcase explosives.

What followed has made survivors wonder for years if more lives could have been saved. Pastora, who suffered burns and fractures, was rushed off by speedboat. According to survivors, the least wounded were among the first to be evacuated – on slow, leaky, outboard-powered dugouts.

Witnesses said it was more than an hour before any of the more seriously injured were attended to by the rebel group’s terrified personnel, who dragged them out of the building, applied tourniquets and administered antibiotic injections, but little else. Reports later revealed they were operating under a triage system and attending first to those they thought would most likely survive.

NEWS of the tragedy arrived in San José around 8 p.m., via radio transmission. The first boatload of victims was met by waiting ambulances in Costa Rica at 9 p.m., after an hour-long trip on the San Juan and San Carlos rivers. The trip to the Ciudad Quesada hospital was another 45 minutes. The evacuation and treatment continued into the evening.

Despite requests for helicopters from the U.S. Embassy and nearby U.S. ranchers with planes and radios, the entire evacuation was done by boat and car.

Death Came before Answers for Outspoken Journalist

UNPARALLELED dedication to uncovering the truth about the La Penca bombing died last year with the death of foreign press correspondent Roberto Cruz. The explosion took from him a leg, eye and hearing in his left ear, and fueled his drive to seek justice for the terrorist act until his death (TT, Feb. 28, 2003).

“There have been no accusations or arrests made of those involved in the massacre of journalists,” Cruz told The Tico Times in a 2001 interview. “The continued cover-up makes a mockery of justice and of the journalists who lost their lives.”

Cruz maintained the assassination plot was authored by CIA officials working with high-ranking members of the Costa Rican and U.S. governments.

IN May 1999, after years of accumulating additional testimonies and documentation to support his case, he – along with family members of the two Channel 6 staffers killed in the blast – filed a criminal case before the Costa Rican court system (TT June 8, 2001).

The case, handled by Costa Rican prosecutor Paula Guido, will come to a close in the near future with her final report, she said this week. She said she is preparing to present it and her conclusions to a Costa Rican judge in the future, but did not say when.

No one has picked up the torch that Guatemalan-born Cruz dropped when he died at age 67, and Guido says she does not believe any new evidence will surface.

JOURNALIST Martha Honey, who conducted an 18-month investigation of the bombing with her husband Tony Avirgan, also injured by the bomb, said Cruz “was terribly wounded both physically and psychologically because of La Penca, and he struggled to get to the truth of it. In my mind, he is the real hero and needs to be remembered,” she added.