The controversy this week over the nonexistent U.S. military base in Costa Rica brings to mind the year 1985, when U.S. Green Berets were training Costa Rican “policemen” in Murciélago, just north of the Santa Rosa Peninsula in Guanacaste.

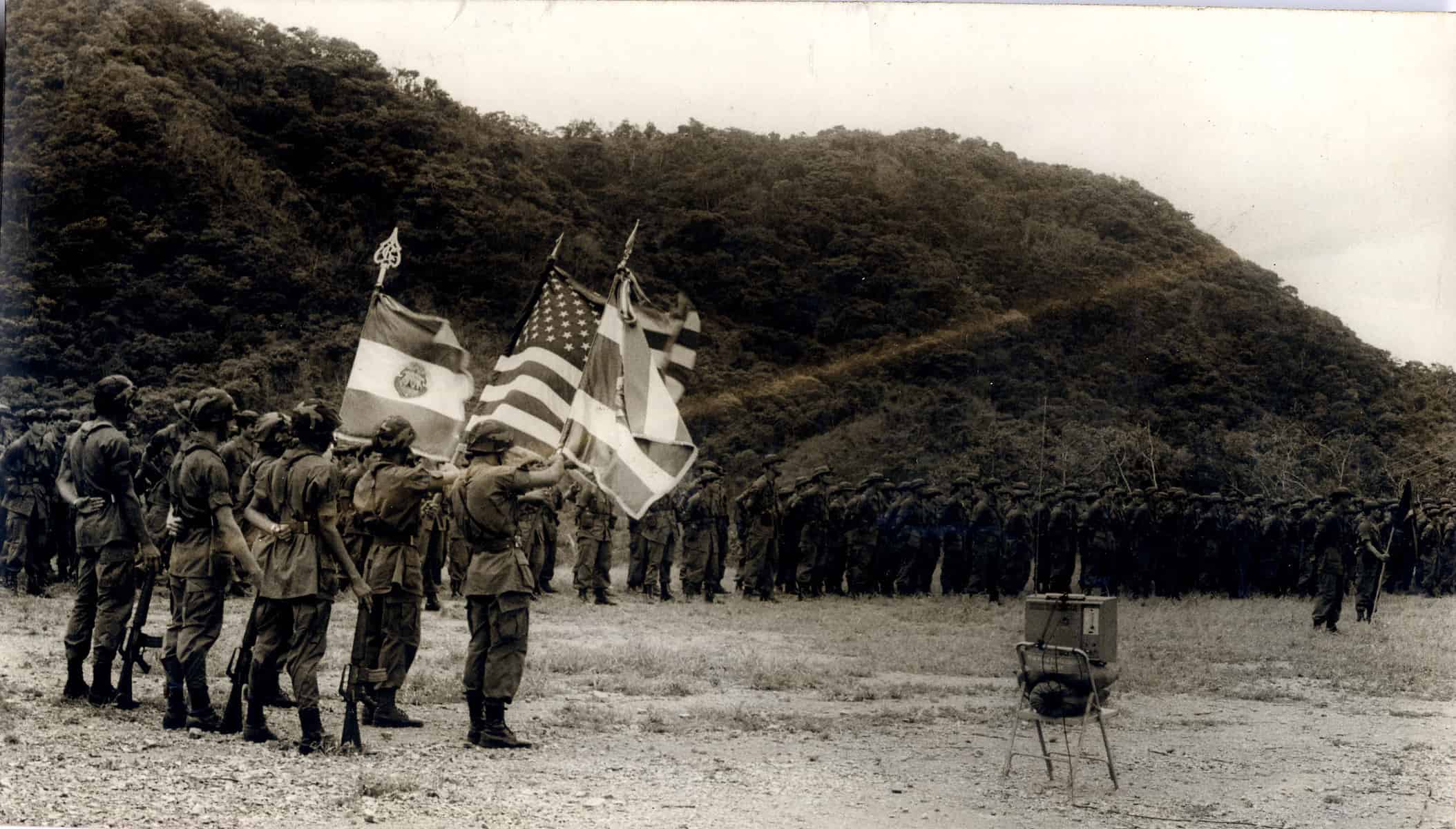

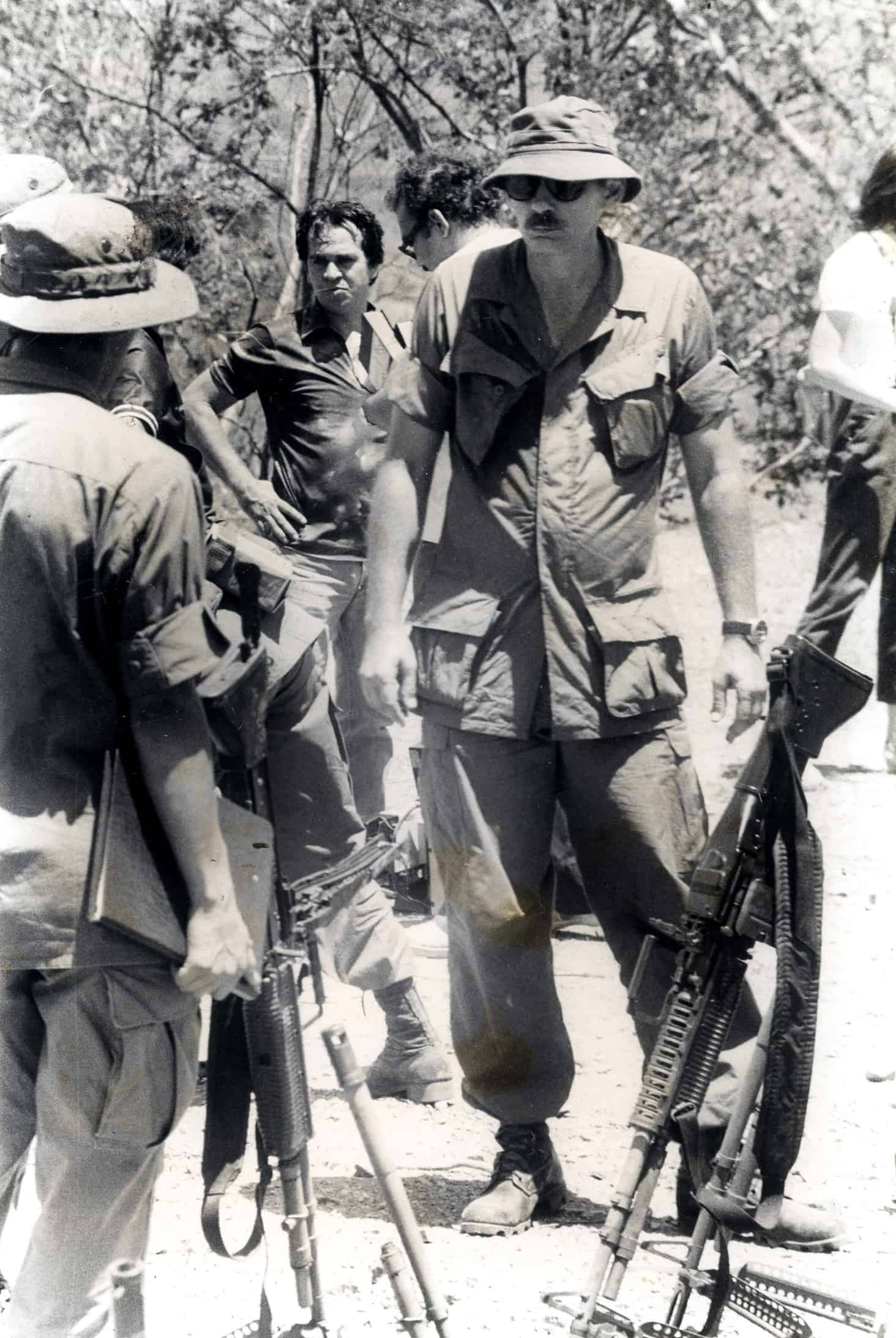

The training took place on a former ranch expropriated from Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza near the Nicaraguan border. Authorities invited members of the press to the graduation of a platoon of “policemen,” with The Tico Times’ María Elena Esquivel coming away with photos of olive-green-clad troops marching with both Costa Rican and U.S. flags.

Then-Public Security Minister Benjamin Piza was seen on national television that night pinning medals on individual troops – not designating them “police officers,” but rather “infantry soldiers.”

The context of the event was the Contra war in neighboring Nicaragua, of which the southern front was being run surreptitiously during the government of Luis Alberto Monge which, sorely divided by the issue, put up some resistance.

In its public diplomacy campaign in favor of the Contras, the U.S. Embassy published polls stating that the majority of Costa Ricans supported the Contra cause. But the graduation event sparked controversy reminiscent of this week’s outcry over the U.S. “military base,” albeit in the days before social media.

An event to protest the “militarization” of the country’s police forces was held at San Jose’s Legislative Assembly, and many luminaries attended, first among them former President José “Pepe” Figueres, the man who abolished Costa Rica’s army on Dec. 1, 1948.

Don Pepe said President Monge probably didn’t have a choice but to permit the military training due to the massive economic assistance the U.S. was providing Costa Rica’s tottering economy. But Figueres did not, as might have been expected in other parts of Latin America, use the occasion to rail against “Yankee” imperialism.

Instead, he embarked on a long and somewhat convoluted dissertation on the evils of tribalism, identifying it years before events in Bosnia and Rwanda as the fundamental iniquity facing mankind. Such was the genius of Don Pepe.

I don’t recall if presidential candidate Óscar Arias was among those at the Assembly protest. I am certain – because Arias himself has said so –that the candidate’s own polls were telling him something very different about the mood of the Costa Rican people regarding the war in neighboring Nicaragua. The great majority, it turned out, was deeply concerned about the possibility of Costa Rica being dragged militarily into the Central American maelstrom.

Even as police were receiving military training from Green Berets, Arias launched a campaign reminding Costa Ricans of their national vocation of peace and promising to work to end the wars at the country’s doorstep.

What ensued is now history: Arias scored a come-from-behind win over the right-leaning Rafael Ángel Calderón Fournier in February 1986, declared his intention to bring peace to Central America based on the moral authority of a country without an army, and proceeded to back up his talk with a diplomatic campaign among Central American presidents that yielded the Esquipulas II peace accords signed in Guatemala in August 1987, garnering Arias the Nobel Peace Prize that year.

In addition to informing U.S. diplomats the country would no longer serve as a Contra base, Arias also took steps to demilitarize and professionalize the Costa Rican police.

He removed military ranks for police officers, and his National Liberation Party helped sponsor a new police statute to professionalize police training, institutionalizing the nonmilitary nature of the training into law.

None of this ought to be surprising. Civilian values are bound into Costa Rica’s civic DNA, which anyone can see on major holidays where parades feature uniformed schoolchildren, not uniformed soldiers. The basic nonmilitary outlook of Ticos is part of the national lore.

One story goes that early last century, when Costa Rica still had an army, authorities had trouble mustering troops, but did manage to recruit a platoon of indigenous soldiers. The troops, who didn’t understand Spanish, had trouble responding to the marching orders of “left, right, left, right.”

A resourceful officer taught the indigenous troops the word for “sandal,” had the troops take off a sandal and then had them march to the cadence of “sandal, no-sandal, sandal, no-sandal.”

Thus was the crack training of the Costa Rican military last century.

And everyone in Costa Rica over a certain age still remembers the times before when the Cold War set it and Tico policemen carried screwdrivers in their holsters instead of guns, to remove license plates of offending auto-parkers.

These, though, are different, scarier times.

The Cold War has been replaced by drug trafficking, and cartels have more resources than governments. Police forces across the Americas have been militarized to deal with the scourge, and Costa Rica’s police haven’t been left too far behind.

Brawny specialized units carry automatic rifles and wear hoods to conceal their identities, looking like soldiers. Police officers wear dress uniforms on special occasions with decidedly non-civilian breast ribbons.

In his second term, Arias told a group of peace activists in 2007 that he would stop sending officers to the U.S. Western Hemisphere Institute of Security Cooperation (formerly the School of the Americas), but he apparently had a change of heart.

If indeed these are signs of mission creep in the area of militarization, you can bet that it is being carried out in spite of a large body of opposing Tico public opinion evidenced by this week’s outcry against the phantom U.S. military base.

And in the end, with civilian judicial officials – not the police – at the head of the “war on drugs,” the relative success Ticos have found compared to their army-bound neighbors speaks to the enduring wisdom of Don Pepe’s decision to heed the words of the founder of the republic, José María Castro Madriz, inscribed at the entrance to Legislative Assembly chambers: “The sword is the enemy of freedom. Let us not give it power.”

Following are some of María Elena Esquivel’s original photos of Murciélago, 1985:

Formerly a reporter and assistant editor at The Tico Times, John McPhaul is a freelance writer.